Subsections

Wellbore stability is critical for drilling.

A stable open-hole requires the surrounding sediment and rock to bear the stresses that amplify around the wellbore cavity.

The surrounding rock must hold stresses until casing is set or for undetermined time if left uncased.

Wellbore stability depends on two set of variables (Figure 6.1): one set which is out of our control and another set of variables that we can control.

- In-situ variables out of our control include far-field stresses

, pore presssure

, pore presssure  , and rock properties.

, and rock properties.

- Controllable variables include mud pressure

(

( for wellbore), mud composition, mud fluid chemistry, and wellbore orientation (direction azimuth and deviation).

for wellbore), mud composition, mud fluid chemistry, and wellbore orientation (direction azimuth and deviation).

Figure 6.1:

Wellbore stability analysis includes inherent variables, such as in-situ stresses and rock properties, and controllable variables, such as wellbore orientation and mud pressure during drilling.

|

The pressure in the wellbore  is one of the main variables to maintain wellbore stability.

Mud (mass) density and vertical depth

is one of the main variables to maintain wellbore stability.

Mud (mass) density and vertical depth  (TVD) determine the mud hydrostatic pressure (in the absence of additional pressure controls at the surface - such as in managed pressure drilling):

(TVD) determine the mud hydrostatic pressure (in the absence of additional pressure controls at the surface - such as in managed pressure drilling):

|

(6.1) |

The pressure gradient within the wellbore is proportional to mud density

(Fig. 6.2).

This quantity is usually measured and reported in p.p.g. (pounds-force per gallon).

For example the pressure gradient for fresh water is 9,800 N/m

(Fig. 6.2).

This quantity is usually measured and reported in p.p.g. (pounds-force per gallon).

For example the pressure gradient for fresh water is 9,800 N/m (= 9.8 MPa/km = 0.44 psi/ft), about 8.3 ppg.

The lithostatic gradient of 1 psi/ft is equivalent to 1 (psi/ft)

(= 9.8 MPa/km = 0.44 psi/ft), about 8.3 ppg.

The lithostatic gradient of 1 psi/ft is equivalent to 1 (psi/ft)  (8.3 ppg/0.44 (psi/ft)) = 18.9 ppg.

The “equivalent circulation density” is also reported in ppg and take into account pressure drops in the annulus.

(8.3 ppg/0.44 (psi/ft)) = 18.9 ppg.

The “equivalent circulation density” is also reported in ppg and take into account pressure drops in the annulus.

Figure 6.2:

Wellbore mud pressure and equivalent density. Mud pressure  is usually reported in terms of gradient (depth-independent) rather than in absolute values.

is usually reported in terms of gradient (depth-independent) rather than in absolute values.

|

Over-balanced drilling implies  .

Over-balanced drilling favors the formation of a “mud-cake” or “filter-cake” on the wall of the wellbore which permits adding stress support on the wellbore wall approximately equal to

.

Over-balanced drilling favors the formation of a “mud-cake” or “filter-cake” on the wall of the wellbore which permits adding stress support on the wellbore wall approximately equal to  (Fig. 6.4).

The resulting effect is similar to an impermeable and elastic membrane applying a stress on the wellbore wall (similar to the membranes used in triaxial tests).

Under-balanced drilling

(Fig. 6.4).

The resulting effect is similar to an impermeable and elastic membrane applying a stress on the wellbore wall (similar to the membranes used in triaxial tests).

Under-balanced drilling  may be preferred in some specific instances.

may be preferred in some specific instances.

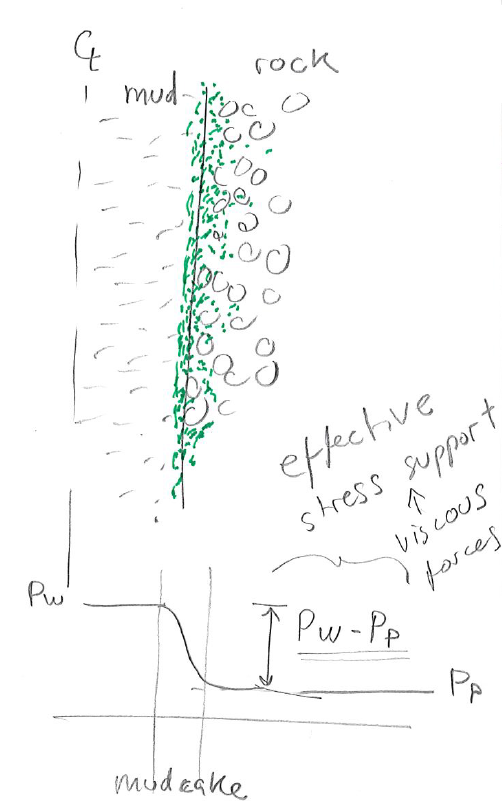

Figure 6.3:

Leak-off of mud filtrate favors clogging of mud particulates which help apply a normal stress on the wellbore wall. This layer of particulates is called mud-cake.

|

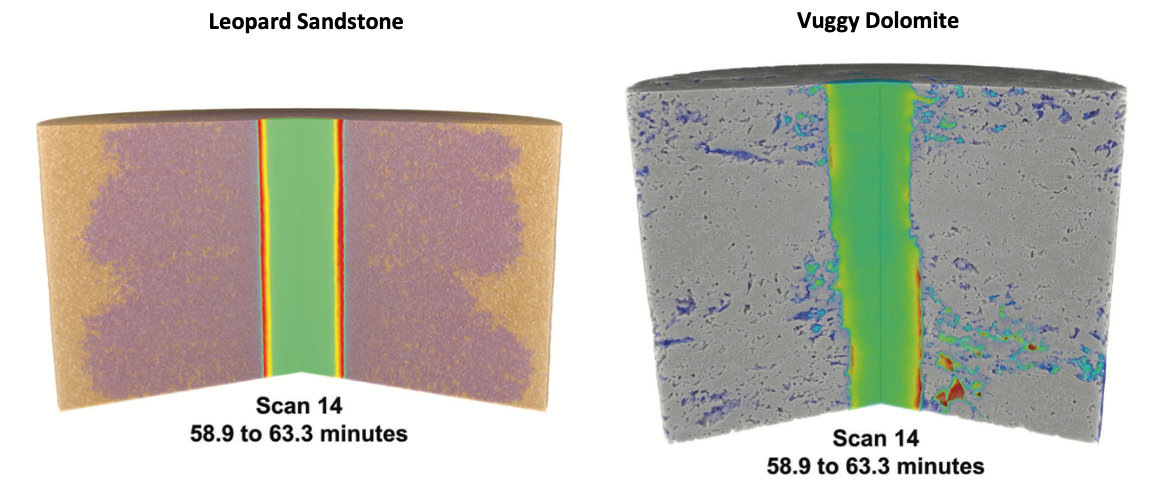

Figure 6.4:

Examples of mud buildup (warm colors) and filtrate/leak-off (cool colors) in two different rock samples as imaged trough time-lapse X-ray tomography. The buildup of mud with time makes the mudcake or filtercake. Image credit: https://doi.org/10.30632/PJV63N5-2022a4.

|

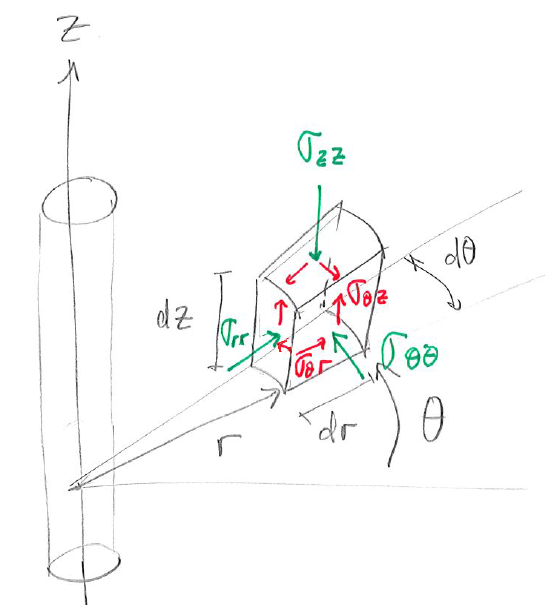

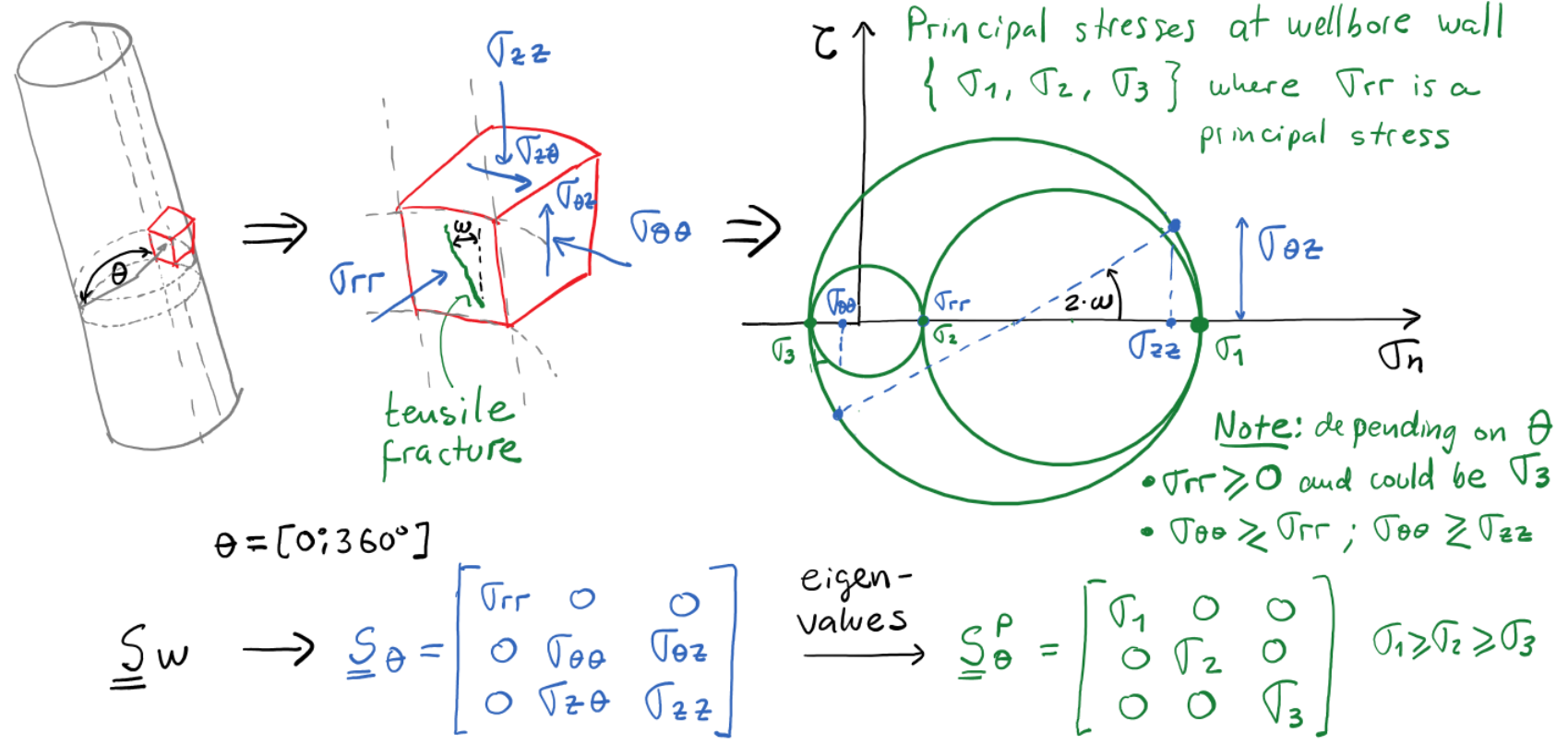

The cylindrical symmetry of a wellbore prompts the utilization of a cylindrical coordinate system rather than a rectangular cartesian coordinate system.

The volume element of stresses in cylindrical coordinates is shown in Fig. 6.5.

The distance  is measured from the center axis of the wellbore.

The angle

is measured from the center axis of the wellbore.

The angle  is measured with respect to a predefined plane.

is measured with respect to a predefined plane.

Figure 6.5:

Infinitesimal volume element in cylindrical coordinates and associated normal and shear stresses.

|

The normal stresses are radial stress

, tangential or hoop stress

, tangential or hoop stress

, and axial stress

, and axial stress

.

The shear stresses are

.

The shear stresses are

,

,

, and

, and

.

.

The Kirsch solution allows us to calculate normal and shear stresses around a circular cavity in a homogeneous linear elastic solid .

The complete Kirsch solution assumes independent action of multiple factors, namely far-field isotropic stress, deviatoric stress, wellbore pressure and pore pressure.

- Isotropic far-field stress: The solution for a compressive isotropic far field stress

is shown in Fig. 6.6.

The presence of the wellbore amplifies compressive stresses 2 times

is shown in Fig. 6.6.

The presence of the wellbore amplifies compressive stresses 2 times

all around the wellbore wall in circumferential direction.

The presence of the wellbore cavity also creates infinitely large stress anisotropy at the wellbore wall

all around the wellbore wall in circumferential direction.

The presence of the wellbore cavity also creates infinitely large stress anisotropy at the wellbore wall

all around the wellbore wall, since

all around the wellbore wall, since

in this case.

Stresses decrease inversely proportional to

in this case.

Stresses decrease inversely proportional to  and are neglible at

and are neglible at  4 radii from the wellbore wall.

4 radii from the wellbore wall.

Figure 6.6:

Kirsch solution for far field isotropic stress

.

.

|

- Inner wellbore pressure: The solution for fluid wall pressure in the wellbore

is shown in Fig. 6.7.

We assume a non-porous solid now.

This assumption will be relaxed later on.

Wellbore pressure adds compression on the wellbore wall

is shown in Fig. 6.7.

We assume a non-porous solid now.

This assumption will be relaxed later on.

Wellbore pressure adds compression on the wellbore wall

, and induces cavity expansion and tensile hoop stresses

, and induces cavity expansion and tensile hoop stresses

all around the wellbore.

all around the wellbore.

Figure 6.7:

Kirsch solution for wellbore pressure  .

.

|

- Deviatoric stress: The solution for a deviatoric stress

aligned with

aligned with

is shown in Fig. 6.8.

The deviatoric stress results in compression on the wellbore wall

is shown in Fig. 6.8.

The deviatoric stress results in compression on the wellbore wall

at

at

and

and  , and in tension

, and in tension

at

at

and

and  .

Hence, the presence of the wellbore amplifies compressive stresses 3 times

.

Hence, the presence of the wellbore amplifies compressive stresses 3 times

at

at

and

and  .

The variation of stresses around the wellbore depend on harmonic functions

.

The variation of stresses around the wellbore depend on harmonic functions

and

and

.

.

Figure 6.8:

Kirsch solution for far-field deviatoric stress

.

.

|

- Pore pressure: The last step consists in assuming a perfect mud-cake, so that, the effective stress wall support (as shown in Fig. 6.7) is

instead of

instead of  .

.

Consider a vertical wellbore subjected to horizontal stresses  and

and  , both principal stresses, vertical stress

, both principal stresses, vertical stress  , pore pressure

, pore pressure  , and wellbore pressure

, and wellbore pressure  .

The corresponding effective in-situ stresses are

.

The corresponding effective in-situ stresses are

,

,

, and

, and  .

The Kirsch solution for a wellbore with radius

.

The Kirsch solution for a wellbore with radius  within a linear elastic and isotropic solid is:

within a linear elastic and isotropic solid is:

|

(6.2) |

where

is the radial effective stress,

is the radial effective stress,

is the tangential (hoop) effective stress,

is the tangential (hoop) effective stress,

is the shear stress in a plane perpendicular to

is the shear stress in a plane perpendicular to  in tangential direction

in tangential direction  , and

, and

is the vertical effective stress in direction

is the vertical effective stress in direction  .

The angle

.

The angle  is the angle between the direction of

is the angle between the direction of  and the point at which stress is considered.

The distance

and the point at which stress is considered.

The distance  is measured from the center of the wellbore.

For example, at the wellbore wall

is measured from the center of the wellbore.

For example, at the wellbore wall  .

.

An example of the solution of Kirsch equations for

MPa,

MPa,

MPa, and

MPa, and

MPa is available in Figure 6.9.

The plots show radial

MPa is available in Figure 6.9.

The plots show radial

and tangential

and tangential

effective stresses, as well as the calculated principal stresses

effective stresses, as well as the calculated principal stresses  and

and

.

.

Figure 6.9:

Example of solution of Kirsch equations. The effective radial stress at the wellbore wall is

. Top: solution for radial

. Top: solution for radial

and hoop

and hoop

stresses. Bottom: solution for principal stresses (eigenvalues from

stresses. Bottom: solution for principal stresses (eigenvalues from

,

,

, and

, and

). Notice that

). Notice that  is the highest at top and bottom and

is the highest at top and bottom and  is the lowest at the sides. The influence of the cavity extend to a few wellbore radii.

is the lowest at the sides. The influence of the cavity extend to a few wellbore radii.

|

Let us obtain

and

and

at the wellbore wall

at the wellbore wall  .

The radial stress for all

.

The radial stress for all  is

is

|

(6.3) |

The hoop stress depends on  ,

,

|

(6.4) |

and it is the minimum at

and

and  (azimuth of

(azimuth of  ) and the maximum at

) and the maximum at

and

and  (azimuth of

(azimuth of  ):

):

|

(6.5) |

These locations will be prone to develop tensile fractures (

and

and  ) and shear fractures (

) and shear fractures (

and

and  ).

The shear stress around the wellbore wall is

).

The shear stress around the wellbore wall is

.

This makes sense because fluids (drilling mud) cannot apply steady shear stresses on the surface of a solid.

Finally, the effective vertical stress is

.

This makes sense because fluids (drilling mud) cannot apply steady shear stresses on the surface of a solid.

Finally, the effective vertical stress is

|

(6.6) |

Wellbore breakouts are a type of rock failure around the wellbore wall and occur when the stress anisotropy

surpasses the shear strength limit of the rock.

Maximum anisotropy is found at

surpasses the shear strength limit of the rock.

Maximum anisotropy is found at

and

and  , for which

, for which

|

(6.7) |

Figure 6.10:

Wellbore pressure for initiation of wellbore breakouts. Shear fractures will develop if

.

.

|

Hence, replacing  and

and  into a shear failure equation (Eq. ) permits finding the mud pressure

into a shear failure equation (Eq. ) permits finding the mud pressure

that would produce a tiny shear failure (or breakout) at

that would produce a tiny shear failure (or breakout) at

and

and  :

:

![$\displaystyle \left[

-(P_W - P_p) +3 \: \sigma_{Hmax} -\sigma_{hmin}

\right] = UCS + q \left[ P_W - P_p \right]$](img914.svg) |

(6.8) |

Hence,

|

(6.9) |

Mud pressure

would extend rock failure and breakouts further in the neighborhood of

would extend rock failure and breakouts further in the neighborhood of

and

and  (See Fig. 6.11).

Thus,

(See Fig. 6.11).

Thus,

is the lowest mud pressure before initiation of breakouts.

is the lowest mud pressure before initiation of breakouts.

Figure 6.11:

Example of wellbore breakout [Zoback 2013 - Fig. 6.15]. Observe the inclination of shear fractures as the propagate into the rock. The material that falls into the wellbore is taken out as drilling cuttings.

|

PROBLEM 6.1: Calculate the minimum mud weight (ppg) in a vertical wellbore for avoiding shear failure (breakouts) in a site onshore at 7,000 ft of depth where  4,300 psi and

4,300 psi and  6,300 psi and with hydrostatic pore pressure.

The rock mechanical properties are

6,300 psi and with hydrostatic pore pressure.

The rock mechanical properties are  3,500 psi,

3,500 psi,  0.6, and

0.6, and  = 800 psi.

= 800 psi.

SOLUTION

Hydrostatic pore pressure results in:

The effective horizontal stresses are:

and

The friction angle is

, and therefore, the friction coefficient

, and therefore, the friction coefficient  is

is

Thus, the minimum mud pressure for avoiding shear failure (breakouts) is

psi

This pressure can be achieved with an equivalent circulation density of

For a given set of problem variables (far field stress, pore pressure, and mud pressure), we can calculate the required strength of the rock to have a stable wellbore.

Let us consider the example of Fig. 6.12 that shows the required  to resist shear failure assuming the friction angle is

to resist shear failure assuming the friction angle is

.

For example, if the rock had a

.

For example, if the rock had a

MPa, one may expect a

MPa, one may expect a

wide breakout in Fig. 6.12.

wide breakout in Fig. 6.12.

Figure 6.12:

Example of required  with Mohr-Coulomb analysis to verify likelihood of wellbore breakouts.

with Mohr-Coulomb analysis to verify likelihood of wellbore breakouts.

|

Alternatively, you could solve the previous problem analytically.

The procedure consists in setting shear failure at the point in the wellbore at an angle

from

from  or

or  .

Hence, at a point on the wellbore wall at

.

Hence, at a point on the wellbore wall at

:

:

|

(6.10) |

Figure 6.13:

Determination of breakout angle with Mohr-Coulomb failure criterion.

|

Say hoop stress reaches the maximum principal stress anisotropy allowed by the Mohr-Coulomb shear failure criterion (

) where the breakout begins (rock about to fail - Fig. 6.13), then

) where the breakout begins (rock about to fail - Fig. 6.13), then

![$\displaystyle \left[ -(P_W - P_p) + (\sigma_{Hmax} + \sigma_{hmin})

- 2(\sigma_{Hmax} - \sigma_{hmin}) \cos (2 \theta_B) \right]

= UCS + q (P_W - P_p)$](img942.svg) |

(6.11) |

which after some algebraic manipulations results in:

![$\displaystyle 2 \theta_B = \arccos \left[ \frac{ \sigma_{Hmax} + \sigma_{hmin} - UCS - (1+q)(P_W - P_p)}{2(\sigma_{Hmax} - \sigma_{hmin})} \right]$](img943.svg) |

(6.12) |

The breakout angle is

|

(6.13) |

The procedure assumes the rock in the breakout (likely already gone) is still resisting hoop stresses and therefore it is not accurate for large breakouts (

).

).

You could also calculate the wellbore pressure for a predetermined breakout angle by rearranging Eq. 6.12 to

|

(6.14) |

PROBLEM 6.2: Calculate the breakout angle in a vertical wellbore for a mud weight of 10 ppg in a site onshore at 7,000 ft of depth where  4,300 psi and

4,300 psi and  6,300 psi and with hydrostatic pore pressure.

The rock mechanical properties are

6,300 psi and with hydrostatic pore pressure.

The rock mechanical properties are  3,500 psi,

3,500 psi,  0.6, and

0.6, and  = 800 psi.

= 800 psi.

SOLUTION

The problem variables are the same of Problem 6.1.

For a 10 ppg mud, the resulting mud pressure is

ppg

Hence, the expected wellbore breakout angle is

Breakouts and tensile induced fractures (Section 6.4) can be identified and measured with borehole imaging tools (Fig. 6.14).

Breakouts appear as wide bands of longer travel time or higher electrical resistivity in borehole images.

Tensile fractures appear as narrow stripes of longer travel time or higher electrical resistivity.

Borehole images also permit identifying the direction of the stresses that caused such breakouts or tensile induced fractures.

For example, the azimuth of breakouts coincides with the direction of  in vertical wells.

in vertical wells.

Breakouts can also be detected from caliper measurements.

Caliper tools permit measuring directly the size and shape of the borehole (https://petrowiki.org/Openhole_caliper_logs). Thus, the caliper log is extremely useful to measure breakouts and extended breakouts (washouts). For the same mud density, the caliper log reflects changes of rock properties along the well and correlate with other well logging measurements.

Breakouts are a consequence of stress anisotropy in the plane perpendicular to the wellbore.

Hence, knowing the size and orientation of breakouts permits measuring and calculating the direction and magnitude of stresses that caused such breakouts.

This technique is very useful for measuring orientation of horizontal stresses.

In addition, if we know the rock properties  and

and  , then it is possible to calculate the maximum principal stress in the plane perpendicular to the wellbore. For example, for a vertical wellbore the total maximum horizontal stress would be

, then it is possible to calculate the maximum principal stress in the plane perpendicular to the wellbore. For example, for a vertical wellbore the total maximum horizontal stress would be

![$\displaystyle S_{Hmax} = P_p + \frac{UCS + (1+q)(P_W - P_p)

- \sigma_{hmin} \left[ 1 + 2 \cos (\pi - w_{BO}) \right]}

{1 - 2 \cos (\pi - w_{BO})}$](img951.svg) |

(6.15) |

6.4 Tensile fractures and wellbore breakdown

Wellbore tensile (or open mode) fractures occur when the minimum principal stress  on the wellbore wall goes below the limit for tensile stress: the tensile strength

on the wellbore wall goes below the limit for tensile stress: the tensile strength  .

Unconsolidated sands have no tensile strength.

Hence, an open-mode fracture occurs early after effective stress goes to zero.

The minimum hoop stress is located on the wall of the wellbore

.

Unconsolidated sands have no tensile strength.

Hence, an open-mode fracture occurs early after effective stress goes to zero.

The minimum hoop stress is located on the wall of the wellbore  and at

and at  and

and  (Fig. 6.15):

(Fig. 6.15):

|

(6.16) |

Notice that we have added a temperature term

that takes into account wellbore cooling, an important phenomenon that contributes to tensile fractures in wellbores.

that takes into account wellbore cooling, an important phenomenon that contributes to tensile fractures in wellbores.

Figure 6.15:

Occurrence of tensile fractures around a vertical wellbore. Tensile fractures will occur when  .

.

|

Matching the lowest value of hoop stress

with tensile strength

with tensile strength  permits finding the mud pressure

permits finding the mud pressure

that would produce a tensile (or open mode) fracture:

that would produce a tensile (or open mode) fracture:

|

(6.17) |

and therefore

|

(6.18) |

The subscript  of

of  corresponds to “breakdown” pressure because in some cases when

corresponds to “breakdown” pressure because in some cases when  , a mud pressure

, a mud pressure  can create a hydraulic fracture that propagates far from the wellbore and causes lost circulation during drilling.

When

can create a hydraulic fracture that propagates far from the wellbore and causes lost circulation during drilling.

When  and

and  , the mud pressure will produce short tensile fractures around the wellbore that do not propagate far from the wellbore.

, the mud pressure will produce short tensile fractures around the wellbore that do not propagate far from the wellbore.

In the equations above we have added the contribution of thermal stresses

![$\sigma^{\Delta T} = [\alpha_T E/(1-\nu)] \Delta T$](img963.svg) where

where  is the linear thermal expansion coefficient and

is the linear thermal expansion coefficient and  is the change in temperature (

is the change in temperature (

for

for

).

Wellbores are usually drilled and logged with drilling mud cooler than the formation

).

Wellbores are usually drilled and logged with drilling mud cooler than the formation

.

Cooling leads to solid shrinkage and stress relaxation (a reduction of compression stresses).

Hence, ignoring thermal stresses is conservative for preventing breakouts but it is not for tensile fractures and should be taken into account when calculating

.

Cooling leads to solid shrinkage and stress relaxation (a reduction of compression stresses).

Hence, ignoring thermal stresses is conservative for preventing breakouts but it is not for tensile fractures and should be taken into account when calculating  .

.

Fig. 6.16 shows an example of calculation of the local minimum principal stress  around a wellbore.

The locations with the lowest stress align with the direction of the far-field maximum stress in the plane perpendicular to wellbore axis.

around a wellbore.

The locations with the lowest stress align with the direction of the far-field maximum stress in the plane perpendicular to wellbore axis.

Figure 6.16:

Example of calculation of tensile strength required for wellbore stability. The figure shows that a tensile strength of  MPa is required to avert tensile fractures in this example.

MPa is required to avert tensile fractures in this example.

|

PROBLEM 6.3: Calculate the maximum mud weight (ppg) in a vertical wellbore for avoiding drilling-induced tensile fractures in a site onshore at 7,000 ft of depth where  4,300 psi and

4,300 psi and  6,300 psi and with hydrostatic pore pressure.

The rock mechanical properties are

6,300 psi and with hydrostatic pore pressure.

The rock mechanical properties are  3,500 psi,

3,500 psi,  0.6, and

0.6, and  = 800 psi.

= 800 psi.

SOLUTION

The problem variables are the same of problem 6.1.

The breakdown pressure  in the absence of thermal effects is

in the absence of thermal effects is

This pressure can be achieved with an equivalent circulation density of

Similarly to breakouts, drilling-induced tensile fractures can be identified and measured with borehole imaging tools (Fig. 6.17).

The azimuth of tensile fractures coincides with the direction of  in vertical wells.

in vertical wells.

Figure 6.17:

Examples of drilling-induced tensile fractures along wellbores as seen with borehole imaging tools. Similarly to breakouts, tensile fractures can also help determine the orientation of the far field stresses.

|

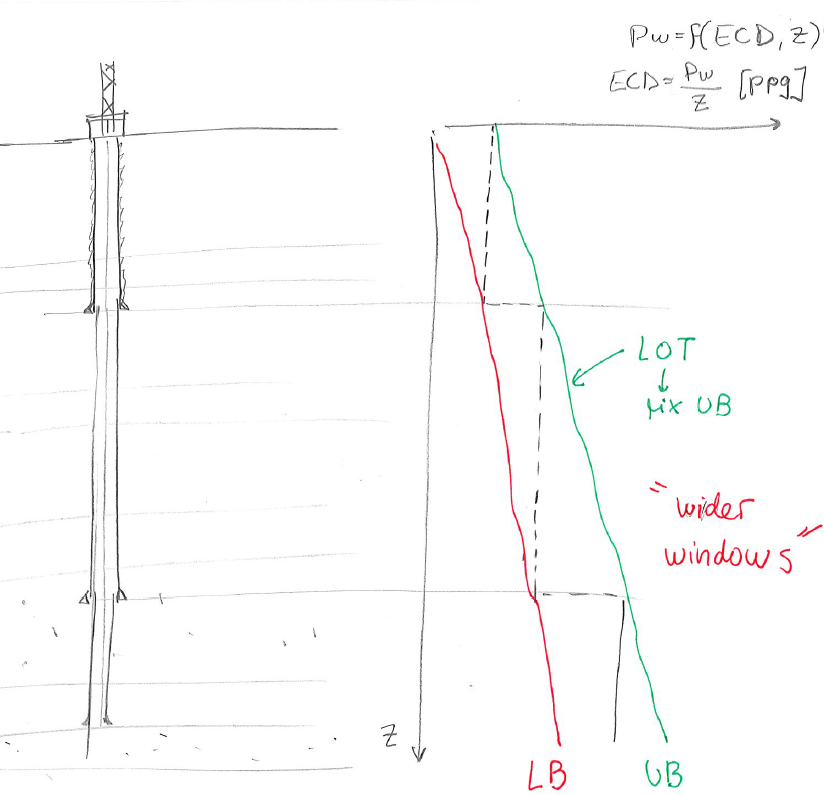

As seen in previous sections, low mud pressure (small mud wall support  for hoop stress

for hoop stress  ) encourages shear failure while too much pressure encourages tensile fractures (well pressure adds tensile hoop stresses).

Hence there is a range of mud pressure for which the wellbore will remain stable during drilling.

This is called the mud window and has a lower bound (LB) and an upper bound (UB) which depend on wellbore mechanical stability as well as in other various technical requirements (Fig. 6.18).

) encourages shear failure while too much pressure encourages tensile fractures (well pressure adds tensile hoop stresses).

Hence there is a range of mud pressure for which the wellbore will remain stable during drilling.

This is called the mud window and has a lower bound (LB) and an upper bound (UB) which depend on wellbore mechanical stability as well as in other various technical requirements (Fig. 6.18).

Figure 6.18:

Mud window based on mechanical wellbore stability, in-situ stresses, and pore pressure. HF: hydraulic fracture, LB: lower bound, and UB: upper bound.

|

Small breakouts

may not compromise wellbore stability and permit setting a lower (more flexible) bound for the mud window.

Large breakouts

may not compromise wellbore stability and permit setting a lower (more flexible) bound for the mud window.

Large breakouts

can lead to extensive shear failure and breakout growth which lead to stuck borehole assemblies and even wellbore collapse.

Likewise, small drilling-induced tensile fractures with wellbore pressure

can lead to extensive shear failure and breakout growth which lead to stuck borehole assemblies and even wellbore collapse.

Likewise, small drilling-induced tensile fractures with wellbore pressure  lower than the minimum principal stress

lower than the minimum principal stress  can be safe and extend the upper bound for the mud window.

However, wellbore pressures above

can be safe and extend the upper bound for the mud window.

However, wellbore pressures above  can result into uncontrolled mud-driven fracture propagation.

Eq. 6.17 may suggest a safe breakdown pressure value above the minimum principal stress

can result into uncontrolled mud-driven fracture propagation.

Eq. 6.17 may suggest a safe breakdown pressure value above the minimum principal stress  .

However, this calculation assumes tensile strength everywhere in the the borehole wall.

Any rock flaw or fracture (

.

However, this calculation assumes tensile strength everywhere in the the borehole wall.

Any rock flaw or fracture ( MPa) may reduce drastically

MPa) may reduce drastically  .

.

There are other factors to take into account in the determination of the mud window in addition to mechanical wellbore stability.

First, a mud pressure below the pore pressure will induce fluid flow from the formation into the wellbore.

The fluid flow rate will depend on the permeability of the formation.

Tight formations may be drilled underbalanced with negligible production of formation fluid.

High mud pressure with respect to the pore pressure will promote mud losses (by leak-off) and damage reservoir permeability.

Second, a mud pressure above the far field minimum principal stress  may cause uncontrolled hydraulic fracture propagation and lost circulation events during drilling.

may cause uncontrolled hydraulic fracture propagation and lost circulation events during drilling.

Maximizing the mud window (by taking advantage of geomechanical understanding among other variables) is extremely important to minimize the number of casing setting points and minimize drilling times (Fig. 6.19).

The mud pressure gradient in a wellbore

is a constant and depends directly on the mud density.

Therefore, drilling designs are based on the mud pressure with respect to a datum (usually the rotary Kelly bushing - RKB) expressed on terms of “equivalent density” to take into account viscous losses.

In any open-hole section the value of pressure

is a constant and depends directly on the mud density.

Therefore, drilling designs are based on the mud pressure with respect to a datum (usually the rotary Kelly bushing - RKB) expressed on terms of “equivalent density” to take into account viscous losses.

In any open-hole section the value of pressure  in a plot equivalent density v.s. depth is a straight vertical line (Fig. 6.2).

The casing setting depth results from a selection of mud densities that cover the range between of the mud window as a function of depth.

Wider mud windows reduce the number of casing setting points.

in a plot equivalent density v.s. depth is a straight vertical line (Fig. 6.2).

The casing setting depth results from a selection of mud densities that cover the range between of the mud window as a function of depth.

Wider mud windows reduce the number of casing setting points.

Figure 6.19:

Drilling mud density and wellbore design. The drilling mud window depends on the lower and upper bounds (LB and UB) determined from geomechanical analysis. Careful geomechanical analysis favors “wider windows” and reduces the number of casing setting depths.

|

Managed pressure drilling consist in modifying the mud pressure at surface (positive or negative increase) or a certain control depth, such that there is one more control on wellbore pressure.

The mud weight determines the gradient.

The surface pressure control can offset the origin of the pressure hydrostatic “line”.

Hence, these two controls can help adjust the pressure along the wellbore to fit in between lower and upper bounds better than just one control (mud weight).

Last, drastic changes in the mud window may happen whenever there is anomalous pore pressure, either too high or too low. Highly overpressured environments are challenging for drilling because of small effective stress and therefore small rock/sediment strength. The mechanisms for overpressure are discussed in Section 2.2. Anomalously low pressure decreases the least principal stress and is usually encountered when drilling through depleted formations that have not been recharged naturally. This topic is explored in Section 2.2.3 and thoroughly documented in a case study listed in Suggested Reading for this chapter.

The following subsections present a guide for calculating stresses at the wall of deviated wellbores and identifying stress magnitudes and locations for shear failure (breakouts) and tensile fractures.

At any point along the trajectory of a deviated wellbore, the tangent orientation permits defining wellbore azimuth  and deviation

and deviation  (Fig. 6.20).

Azimuth

(Fig. 6.20).

Azimuth  is the angle between the projection of the trajectory on a horizontal plane and the North.

Deviation

is the angle between the projection of the trajectory on a horizontal plane and the North.

Deviation  is the angle between a vertical line and the trajectory line at the point of consideration.

These two variables can be plotted in a half-hemisphere projection plot (stereonet).

Notice that a point in this plot represents just one point along a wellbore trajectory.

Fig. 6.20 shows an example of the full trajectory of a wellbore.

is the angle between a vertical line and the trajectory line at the point of consideration.

These two variables can be plotted in a half-hemisphere projection plot (stereonet).

Notice that a point in this plot represents just one point along a wellbore trajectory.

Fig. 6.20 shows an example of the full trajectory of a wellbore.

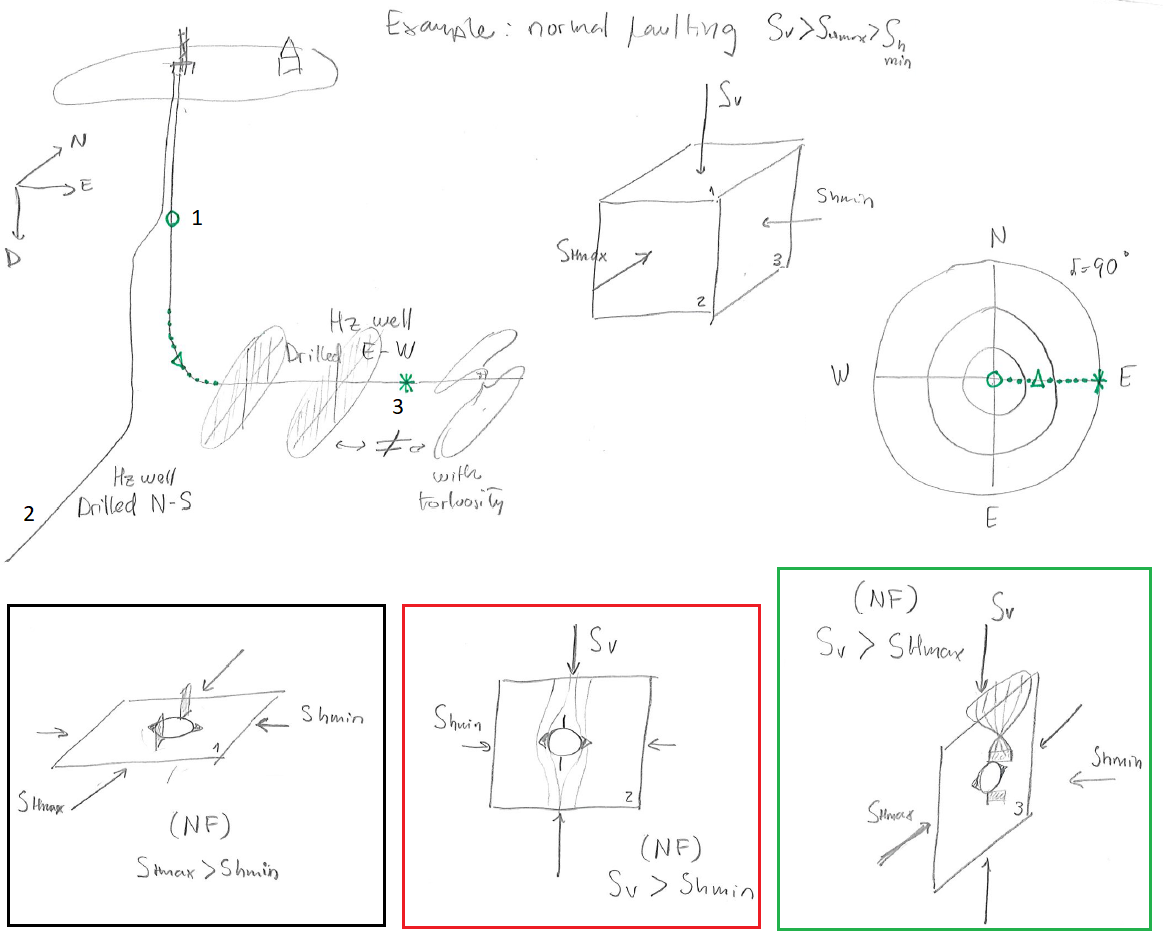

Figure 6.20:

(a) Convention for plotting the orientation of a deviated wellbore on a lower hemisphere projection. (b) The example shows the deviation survey for a real wellbore (deviation range amplified to highlight small deviations). Notice that it starts slightly deviated on surface and then turns into vertical direction at depth.

|

A given state of stress will result in different mud windows and locations of rock failure depending on the wellbore orientation.

Breakouts and tensile fractures will depend on the stresses on the plane perpendicular to the wellbore.

Figure 6.21 shows an example for normal faulting with generic stress magnitude values.

Figure 6.21:

Example of expected location of wellbore breakouts and tensile fractures in a vertical and horizontal wellbores according to the state of stress (normal faulting with  in N-S direction here).

in N-S direction here).

|

PROBLEM 6.4: Consider a place where vertical stress  is a principal stress and the maximum horizontal stress acts in E-W direction.

is a principal stress and the maximum horizontal stress acts in E-W direction.

- Find the planes with maximum stress anisotropy for normal faulting, strike-slip, and reverse faulting stress regimes.

- Plot the orientation of wellbores in those planes of maximum stress anisotropy in a stereonet projection plot.

- Where around the wellbore would breakouts and tensile fractures occur in each case?

SOLUTION

The solution below shows just one of the possible solutions of two horizontal wells.

Let us define a coordinate system for a point along the trajectory of a deviated wellbore.

The first element  of the cartesian base goes from the center of a cross-section of the wellbore at a given depth to the deepest point around the cross-section (perpendicular to the axis).

The second element of the base

of the cartesian base goes from the center of a cross-section of the wellbore at a given depth to the deepest point around the cross-section (perpendicular to the axis).

The second element of the base  goes from the center to the side on a horizontal plane.

The third element of the base

goes from the center to the side on a horizontal plane.

The third element of the base  goes along the direction of the wellbore.

goes along the direction of the wellbore.

Figure 6.22:

The wellbore coordinate system.

|

Based on the previous definition, it is possible to construct a transformation matrix

that links the geographical coordinate system and the wellbore coordinate system.

that links the geographical coordinate system and the wellbore coordinate system.

|

(6.19) |

Furthermore, the wellbore stresses can be calculated from the principal stress tensor according with:

|

(6.20) |

Where

and

and  are the principal stress tensor and the corresponding change of coordinate matrix to the geographical coordinate system (Eq. 5.7).

The tensor

are the principal stress tensor and the corresponding change of coordinate matrix to the geographical coordinate system (Eq. 5.7).

The tensor

is composed by the following stresses:

is composed by the following stresses:

![\begin{displaymath}\uuline{S}{}_W =

\left[

\begin{array}{ccc}

S_{11} & S_{12} & ...

...2} & S_{23} \\

S_{31} & S_{32} & S_{33} \\

\end{array}\right]\end{displaymath}](img992.svg) |

(6.21) |

Stresses on the plane of the cross-section of the deviated wellbore at the wellbore wall

depend on far-field stresses

depend on far-field stresses

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

, and

, and

.

The Kirsch equations require additional far field shear terms

.

The Kirsch equations require additional far field shear terms

,

,

, and

, and

in order to account for principal stresses not coinciding with the wellbore orientation.

The solution of Kirsch equation for isotropic rock with far-field shear stresses is provided in Fig. 6.23.

in order to account for principal stresses not coinciding with the wellbore orientation.

The solution of Kirsch equation for isotropic rock with far-field shear stresses is provided in Fig. 6.23.

Figure 6.23:

Stresses around the wall of a deviated wellbore. Notice that principal stresses (directions

) may not be aligned with the wellbore trajectory.

) may not be aligned with the wellbore trajectory.

|

Solving for the local principal stresses

on the wellbore wall permits checking for rock failure (tensile or shear).

The local principal stresses may not be necessarily aligned with the wellbore axis leading to an angle

on the wellbore wall permits checking for rock failure (tensile or shear).

The local principal stresses may not be necessarily aligned with the wellbore axis leading to an angle  (see Fig. 6.24).

Because of such angle, tensile fractures in deviated wellbores can occur at an angle

(see Fig. 6.24).

Because of such angle, tensile fractures in deviated wellbores can occur at an angle  from the axis of the wellbore and appear as a series of short inclined (en-échelon) fractures instead of a long tensile fracture parallel to the wellbore axis as in Fig. 6.17.

from the axis of the wellbore and appear as a series of short inclined (en-échelon) fractures instead of a long tensile fracture parallel to the wellbore axis as in Fig. 6.17.

Figure 6.24:

Principal stresses around the wall of a deviated wellbore. The hoop stress

could be the least, the intermediate or the maximum principal stress depending on location (angle

could be the least, the intermediate or the maximum principal stress depending on location (angle  ).

).

|

Consider a place subjected to strike-slip stress regime with  oriented at an azimuth of 070

oriented at an azimuth of 070 with known values of principal stresses (Fig 6.25).

The maximum stress anisotropy lies in a plane that contains

with known values of principal stresses (Fig 6.25).

The maximum stress anisotropy lies in a plane that contains

and

and

, a plane perpendicular to the axis of a vertical wellbore.

Hence, maximum stress amplification at the wellbore wall will happen for a vertical wellbore.

The minimum stress anisotropy lies in a plane that contains

, a plane perpendicular to the axis of a vertical wellbore.

Hence, maximum stress amplification at the wellbore wall will happen for a vertical wellbore.

The minimum stress anisotropy lies in a plane that contains

and

and

, perpendicular to a horizontal wellbore drilled in direction of

, perpendicular to a horizontal wellbore drilled in direction of  .

Given a mud pressure and a fixed friction angle, we can calculate for a given wellbore orientation the stresses on the wellbore wall from equations in Fig. 6.24, and the required

.

Given a mud pressure and a fixed friction angle, we can calculate for a given wellbore orientation the stresses on the wellbore wall from equations in Fig. 6.24, and the required  (using a shear failure criterion

(using a shear failure criterion

) to avert shear failure.

The plots in Fig. 6.25 are examples of this calculation.

The maximum value of required

) to avert shear failure.

The plots in Fig. 6.25 are examples of this calculation.

The maximum value of required  corresponds to the wellbore direction with maximum stress anisotropy (vertical wellbore - red region), and the minimum value of required

corresponds to the wellbore direction with maximum stress anisotropy (vertical wellbore - red region), and the minimum value of required  corresponds to the wellbore direction with minimum stress anisotropy (horizontal wellbore with

corresponds to the wellbore direction with minimum stress anisotropy (horizontal wellbore with

- blue region).

Following the breakout concepts discussed before, we would expect breakouts at 160

- blue region).

Following the breakout concepts discussed before, we would expect breakouts at 160 and 340

and 340 of azimuth on the sides of a vertical wellbore.

A horizontal wellbore drilled in the direction of

of azimuth on the sides of a vertical wellbore.

A horizontal wellbore drilled in the direction of  would tend to develop breakouts on the top and bottom of the wellbore.

would tend to develop breakouts on the top and bottom of the wellbore.

Figure 6.25:

Stereonet plots to verify the rock strength required to avoid breakouts and the wellbore breakout angle for a given rock strength and wellbore pressure.

|

PROBLEM 6.5: Consider a place with principal stresses  MPa,

MPa,

MPa (at 070

MPa (at 070 ),

),

MPa,

MPa,  MPa, and

MPa, and  MPa. Calculate the required UCS using the Coulomb failure criterion (with

MPa. Calculate the required UCS using the Coulomb failure criterion (with

) for all possible wellbore orientations.

Plot results in a stereonet projection.

) for all possible wellbore orientations.

Plot results in a stereonet projection.

SOLUTION

PROBLEM 6.6: Consider a place with principal stresses  MPa,

MPa,

MPa (at 070

MPa (at 070 ),

),

MPa,

MPa,  MPa, and

MPa, and  MPa. Calculate the required UCS using the Coulomb failure criterion (with

MPa. Calculate the required UCS using the Coulomb failure criterion (with

) for all possible wellbore orientations.

Plot results in a stereonet projection.

) for all possible wellbore orientations.

Plot results in a stereonet projection.

SOLUTION

A general workflow or algorithm to calculate mechanical failure for all possible wellbore deviations is the following:

- Calculate the stress tensor in the geographical coordinate system:

, given principal stresses

, given principal stresses  and principal stress directions

and principal stress directions

.

.

- Begin a for loop (say counter

), to explore deviation angle from 0 to 90 degrees.

), to explore deviation angle from 0 to 90 degrees.

- Within this first loop, open a second loop (say counter

) to explore azimuth from 0 to 360 degrees.

) to explore azimuth from 0 to 360 degrees.

- For each deviation and azimuth

, calculate stresses in the wellbore coordinate system

, calculate stresses in the wellbore coordinate system  , a function of

, a function of  .

.

- For each deviation and azimuth

, open a third loop (say counter

, open a third loop (say counter  ), to calculate stress at and around the wellbore wall for a cross section with angle from 0 to 360 degrees.

), to calculate stress at and around the wellbore wall for a cross section with angle from 0 to 360 degrees.

- At each point around the well, calculate stresses and get principal stresses.

- For each point along the well, use the principal stresses to predict whether there is failure or not, and what type.

- Save all this failure yes/no/type data

- After checking failure around the well (out of counter

), analyze this data to output a quantity for each orientation (

), analyze this data to output a quantity for each orientation ( ). For example, you could count how many points are failing in shear and get from here the breakout angle.

). For example, you could count how many points are failing in shear and get from here the breakout angle.

- Summarize all your results with a polar projection/stereonet plot.

The procedure to find tensile failure is equivalent to the one used for shear failure, but using a tensile strength failure criterion.

For example, consider a place subjected to normal faulting stress regime with  oriented at an azimuth of 070

oriented at an azimuth of 070 and known values of principal stresses (Fig. 6.26).

The maximum stress anisotropy lies in a plane that contains

and known values of principal stresses (Fig. 6.26).

The maximum stress anisotropy lies in a plane that contains

and

and

, perpendicular to a horizontal wellbore drilled in the direction of

, perpendicular to a horizontal wellbore drilled in the direction of  .

For a given rock tensile strength, we can calculate the maximum mud pressure that the wellbore can bear without failing in tension.

Fig. 6.26 shows an example of this calculation.

The maximum possible

.

For a given rock tensile strength, we can calculate the maximum mud pressure that the wellbore can bear without failing in tension.

Fig. 6.26 shows an example of this calculation.

The maximum possible  corresponds to the wellbore direction with minimum stress anisotropy (blue region), and the minimum possible

corresponds to the wellbore direction with minimum stress anisotropy (blue region), and the minimum possible  corresponds to the wellbore direction with maximum stress anisotropy (red region).

For example, tensile fractures would tend to occur in the top and bottom of a horizontal wellbore drilled in the direction of

corresponds to the wellbore direction with maximum stress anisotropy (red region).

For example, tensile fractures would tend to occur in the top and bottom of a horizontal wellbore drilled in the direction of  .

.

Figure 6.26:

Calculation of required  as a function of wellbore orientation in order to prevent open-mode fractures with

as a function of wellbore orientation in order to prevent open-mode fractures with  MPa. Stresses and pore pressure:

MPa. Stresses and pore pressure:  70 MPa,

70 MPa,

55 MPa,

55 MPa,

45 MPa, and

45 MPa, and  32 MPa, Notice that the stress regimes dictates the orientation of the least and most convenient drilling direction.

32 MPa, Notice that the stress regimes dictates the orientation of the least and most convenient drilling direction.

|

PROBLEM 6.7: Consider a place with principal stresses  MPa,

MPa,

MPa (at 070

MPa (at 070 ),

),

MPa, and

MPa, and  MPa.

Calculate the maximum wellbore pressure

MPa.

Calculate the maximum wellbore pressure  at the limit of tensile strength with

at the limit of tensile strength with  MPa) for all possible wellbore orientations.

Plot results in a stereonet projection.

MPa) for all possible wellbore orientations.

Plot results in a stereonet projection.

SOLUTION

TBD

PROBLEM 6.8: Consider a place with principal stresses  MPa,

MPa,

MPa (at 070

MPa (at 070 ),

),

MPa, and

MPa, and  MPa.

Calculate the maximum wellbore pressure

MPa.

Calculate the maximum wellbore pressure  at the limit of tensile strength with

at the limit of tensile strength with  MPa) for all possible wellbore orientations.

Plot results in a stereonet projection.

MPa) for all possible wellbore orientations.

Plot results in a stereonet projection.

SOLUTION

TBD

Wellbore stability is affected by various factors other than far-field stresses and mud pressure.

Some of the most important factors include: changes of temperature, changes of salinity in the resident brine within the pore space in the rock, and changes of pore pressure near the wellbore wall.

Drilling mud is usually cooler than the geological formations in the subsurface.

Because of such difference, drilling mud usually lowers the temperature of the rock near the wellbore.

The process is time dependent and variations of temperature  in time and space (in the absence of fluid flow) can be modeled using the heat diffusivity equation:

in time and space (in the absence of fluid flow) can be modeled using the heat diffusivity equation:

|

(6.22) |

where heat diffusivity is

proportional to the heat conductivity

proportional to the heat conductivity  , and inversely proportional to the rock mass density

, and inversely proportional to the rock mass density  and the heat capacity

and the heat capacity  .

The operator

.

The operator

indicates variations in space.

The heat diffusivity equation and the equations of thermo-elasticity (Section 3.7.2) permit solving the changes of strains and stresses around the wellbore due to time-dependent changes of temperature.

indicates variations in space.

The heat diffusivity equation and the equations of thermo-elasticity (Section 3.7.2) permit solving the changes of strains and stresses around the wellbore due to time-dependent changes of temperature.

Figure 6.27:

Cooling  leads to stress relaxation and possibly tensile stresses on the wellbore wall.

leads to stress relaxation and possibly tensile stresses on the wellbore wall.

|

At steady-state conditions, the change in hoop stress

around any point on the wellbore wall due to a change in temperature

around any point on the wellbore wall due to a change in temperature  is:

is:

|

(6.23) |

where  is the linear thermal expansion coefficient.

Cooling leads to hoop stress relaxation and possibly tensile effective stress, while heating leads to increased compression in the tangential direction.

is the linear thermal expansion coefficient.

Cooling leads to hoop stress relaxation and possibly tensile effective stress, while heating leads to increased compression in the tangential direction.

Chemo-electrical effects are most relevant to small sub-micron particles, such as clays, the building-blocks of mudrocks and shales.

The forces that act on clay particles include (Figure 6.28):

- Mechanical forces: solid skeletal stress and pore pressure,

- Electrical forces: van der Waals attraction,

Born repulsion, short range repulsive and attractive forces induced by hydration/solvation of clay surfaces.

Figure 6.28:

Schematic of clay platelet pair, forces between them, and equilibrium interparticle distance  .

.

|

Shale chemical instability involves changes of the electrical forces between clay platelets due to changes of ionic concentration of the resident brine within the rock pore space.

The equilibrium distance between particles is inversely proportional to salinity.

Hence, decreasing salinity promotes chemo-electrical swelling of shale (see example in Fig. 6.29).

During drilling, the change in ionic concentration in resident brine is caused by leak-off of low-salinity water from drilling mud into the formation saturated with high salinity brine.

Smectite clays are most sensitive to swelling upon water freshening and hydration.

Figure 6.29:

Example of shale hydration and swelling due to exposure to low salinity water.

|

Shale swelling leads to an increase of hoop stress and sometimes rock weakening around the wellbore wall.

Such changes promote shear failure and breakouts/washouts (Fig. 6.30).

Prevention of shale chemical instability requires modeling of solute diffusive-advective transport between the drilling mud and the formation water in the rock.

Higher mud pressures result in higher leak-off, and therefore, in more rapid ionic exchange within the shale.

The process is time-dependent.

Thus, the expected break out angle results from a combination of mechanical factors (stresses around the wellbore) and shale sensitivity to low salinity muds.

Figure 6.30:

Shale sensitivity: variation of near wellbore stresses and time-dependent breakout angle  prediction example.

prediction example.

|

The solutions to wellbore instability problems due to shale chemo-electrical swelling are: increasing the salinity of water-based drilling muds, using oil-based muds instead of water-based muds, cooling the wellbore to counteract increases of hoop stress, and using

underbalanced-drilling to minimize leak-off of water from drilling mud.

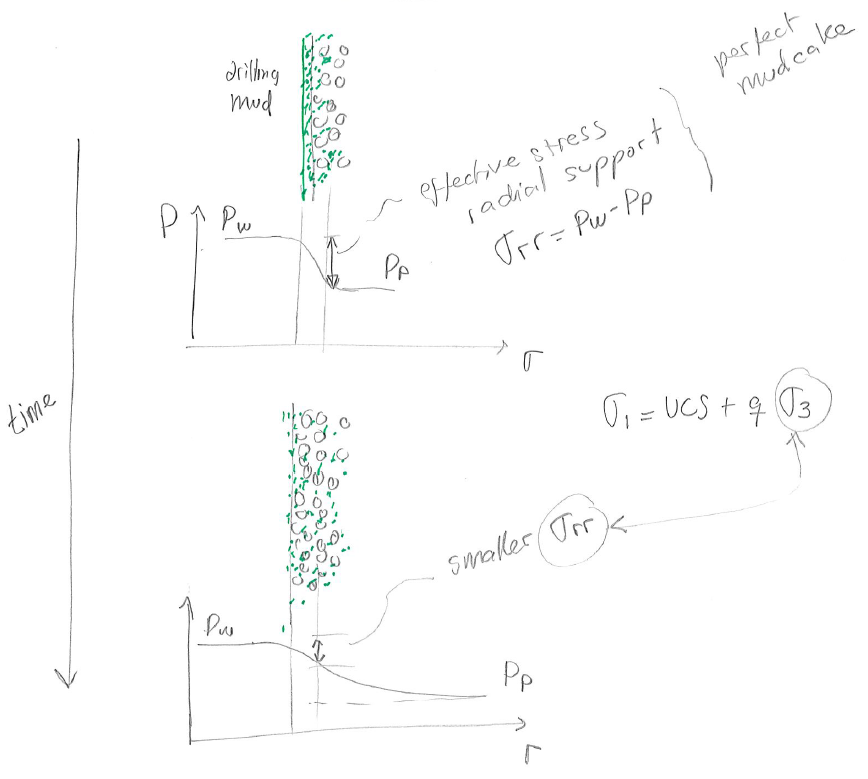

So far we have assumed that the radial effective stress at the wellbore wall is

.

Such assumption implies a perfect and sharp “mudcake” that creates a sharp gradient between the mud pressure and the pore pressure, such that, viscous forces apply an effective stress

.

Such assumption implies a perfect and sharp “mudcake” that creates a sharp gradient between the mud pressure and the pore pressure, such that, viscous forces apply an effective stress

on the wellbore wall (Fig. 6.4).

However, mud water leak off and mud filtration can occur over time decreasing the sharpness of such gradient and reducing the effective stresses in the near wellbore region.

A reduction of effective stress lowers the strength of rock and favors rock failure around the wellbore.

Hence, a wellbore could be stable right after drilling, but unstable after some time due to mud filtration and loss of radial stress support.

on the wellbore wall (Fig. 6.4).

However, mud water leak off and mud filtration can occur over time decreasing the sharpness of such gradient and reducing the effective stresses in the near wellbore region.

A reduction of effective stress lowers the strength of rock and favors rock failure around the wellbore.

Hence, a wellbore could be stable right after drilling, but unstable after some time due to mud filtration and loss of radial stress support.

Figure 6.31:

Loss of mudcake after excessive particle filtration. The loss of mudcake leads to a decrease in effective stress radial support and therefore rock shear strength.

|

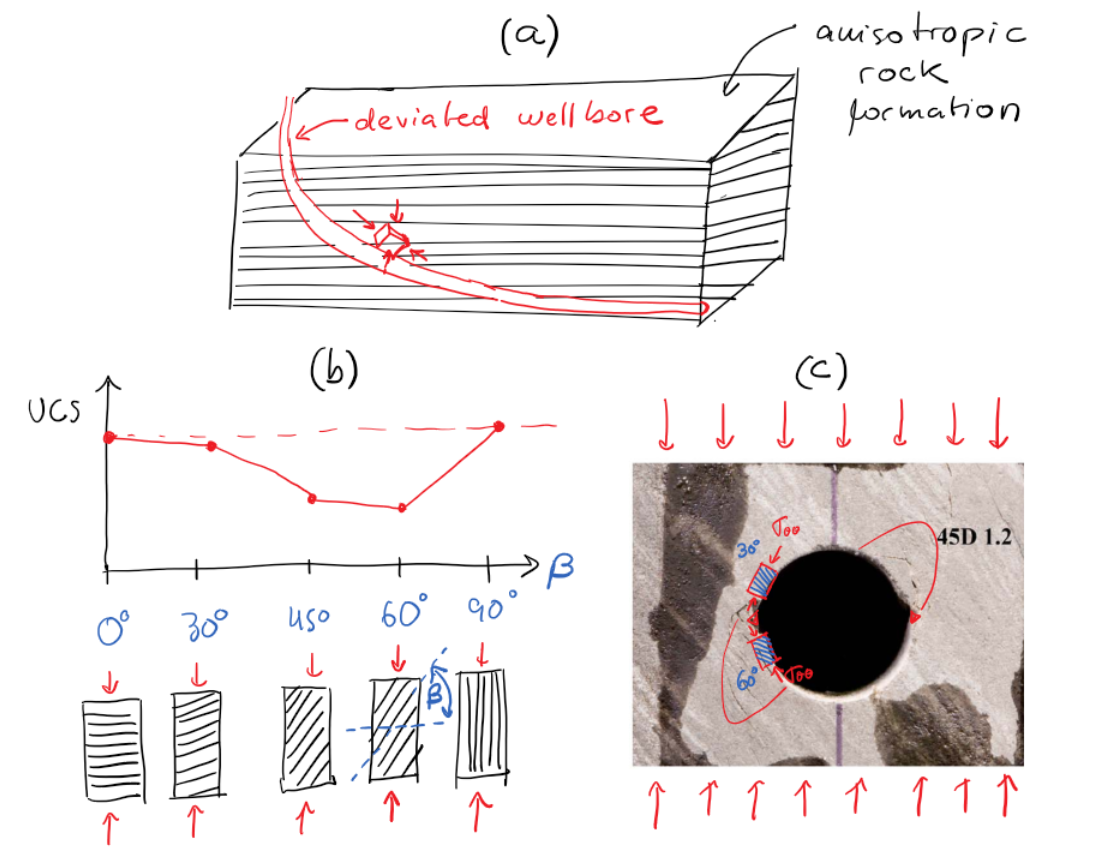

Sedimentary rocks are anisotropic.

Rock lamination contributes to stiffness and strength anisotropy.

Consider a deviated wellbore as in Fig. 6.32.

Far field stress anisotropy will result in high stress anisotropy regions (red zone perpendicular to the direction of maximum stress) and potential breakouts if the strength of intact rock is overcome.

Yet, there will be other areas around the wellbore without such high stress anisotropy but high enough and aligned optimally to induce shear failure in regions weakened by the presence of rock lamination (blue zone).

Such areas may also be prone to develop a second family of breakouts.

- Using equations of stresses around a cylindrical cavity, calculate near-wellbore effective radial

and hoop

and hoop

stresses for a vertical well 8 in diameter in the directions of

stresses for a vertical well 8 in diameter in the directions of  (4,500 psi – acting E-W) and

(4,500 psi – acting E-W) and  (6,000 psi) up to 3 ft of distance considering that

(6,000 psi) up to 3 ft of distance considering that  = 3200 psi and

= 3200 psi and

= 3,200 psi

= 3,200 psi

= 4,000 psi

= 4,000 psi

The result should be presented as plots of stresses (

,

,

) for

) for  and

and

as a function of distance (

as a function of distance ( ) from the center of the wellbore.

) from the center of the wellbore.

- Effect of overpressure:

Consider the problem solved in class (Wellbore: vertical; Site: onshore, 7,000 ft of depth,

= 7,000 psi,

= 7,000 psi,  = 4,300 psi,

= 4,300 psi,  = 6,300 psi; Rock properties:

= 6,300 psi; Rock properties:  = 3,500 psi,

= 3,500 psi,  ,

,  = 800 psi).

= 800 psi).

- Calculate wellbore pressure and corresponding mud weight for (i)

, (ii)

, (ii)

(

(

), and (iii) for inducing tensile fractures (

), and (iii) for inducing tensile fractures ( ) for

) for

and

and

. Compare with

. Compare with

solved in class. How does the drilling mud window change with varying pore pressure?

solved in class. How does the drilling mud window change with varying pore pressure?

- Assume horizontal stress directions near Dallas-Fort Worth region. What would the azimuth of breakouts and drilling induced fractures be? https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-020-15841-5/figures/1

- Effect of stress anisotropy (differential stress)

:

Consider the following problem, Wellbore: vertical; Site: onshore, 2 km of depth,

:

Consider the following problem, Wellbore: vertical; Site: onshore, 2 km of depth,

MPa/km,

MPa/km,

,

,

; Rock properties:

; Rock properties:  = 7 MPa,

= 7 MPa,  ,

,  = 2 MPa. Calculate wellbore pressure and corresponding mud weight for (i)

= 2 MPa. Calculate wellbore pressure and corresponding mud weight for (i)

, (ii)

, (ii)

, and (iii) for inducing tensile fractures for

, and (iii) for inducing tensile fractures for

-

-

-

- How does the drilling mud window change with

?

?

- Offshore:

Consider an offshore vertical wellbore being drilled at 2 km of total vertical depth, with 500 m of water, hydrostatic pore pressure,

,

,

. The rock properties are

. The rock properties are  = 7 MPa,

= 7 MPa,  ,

,  = 2 MPa. Calculate wellbore pressure and corresponding mud weight for (i)

= 2 MPa. Calculate wellbore pressure and corresponding mud weight for (i)

, (ii)

, (ii)

, and (iii) for inducing tensile fractures.

, and (iii) for inducing tensile fractures.

- Horizontal wells:

Evaluate wellbore stability for horizontal wells that you will need to exploit in a gas reservoir subjected to a strike-slip stress environment.

- Consider two wellbores: one drilled parallel to

and another drilled parallel to

and another drilled parallel to  . Draw cross-sections of these two wells, identify involved stresses, and clearly mark expected positions of tensile fractures and wellbore breakouts.

. Draw cross-sections of these two wells, identify involved stresses, and clearly mark expected positions of tensile fractures and wellbore breakouts.

- The horizontal wells lie at about 8,000 ft depth where it is estimated that

= 50 MPa,

= 50 MPa,  = 70 MPa,

= 70 MPa,

psi/ft and

psi/ft and

. The unconfined compressive strength of the rock is 8,500 psi, the rock internal friction coefficient is

. The unconfined compressive strength of the rock is 8,500 psi, the rock internal friction coefficient is  , and tensile strength is about

, and tensile strength is about  psi given the large density of natural fractures. Determine the mechanical stability limits on wellbore pressure for both horizontal well directions considered. Assume a breakout angle

psi given the large density of natural fractures. Determine the mechanical stability limits on wellbore pressure for both horizontal well directions considered. Assume a breakout angle

to calculate the lower bound for the mud window.

to calculate the lower bound for the mud window.

- Determine mud density window appropriate for these wells (keep in mind potential lost circulation).

- Which one appears to have a wider mud window? Justify

- Fjaer, E., Holt, R.M., Raaen, A.M., Risnes, R. and Horsrud, P., 2008. Petroleum related rock mechanics (Vol. 53). Elsevier. (Chapters 4 and 9)

- Heggheim T. and J. Andrews, 2023, Learnings from Successful Drilling in Heavily Depleted HPHT Reservoir with Up to 460 Bar Depletion. IADC/SPE-212526-MS. https://doi.org/10.2118/212526-MS

- Jaeger, J.C., Cook, N.G. and Zimmerman, R., 2009. Fundamentals of rock mechanics. John Wiley & Sons. (Chapter 8)

- Zoback, M.D., 2010. Reservoir geomechanics. Cambridge University Press. (Chapters 6 and 8)

, pore presssure

, pore presssure  , and rock properties.

, and rock properties.

(

( for wellbore), mud composition, mud fluid chemistry, and wellbore orientation (direction azimuth and deviation).

for wellbore), mud composition, mud fluid chemistry, and wellbore orientation (direction azimuth and deviation).

![\includegraphics[scale=0.45]{.././Figures/split/8-WellIntro.PNG}](img871.svg)

![\includegraphics[scale=0.85]{.././Figures/split/7-ECD.pdf}](img874.svg)

is shown in Fig. 6.6.

The presence of the wellbore amplifies compressive stresses 2 times

is shown in Fig. 6.6.

The presence of the wellbore amplifies compressive stresses 2 times

all around the wellbore wall in circumferential direction.

The presence of the wellbore cavity also creates infinitely large stress anisotropy at the wellbore wall

all around the wellbore wall in circumferential direction.

The presence of the wellbore cavity also creates infinitely large stress anisotropy at the wellbore wall

all around the wellbore wall, since

all around the wellbore wall, since

in this case.

Stresses decrease inversely proportional to

in this case.

Stresses decrease inversely proportional to  and are neglible at

and are neglible at  4 radii from the wellbore wall.

4 radii from the wellbore wall.

is shown in Fig. 6.7.

We assume a non-porous solid now.

This assumption will be relaxed later on.

Wellbore pressure adds compression on the wellbore wall

is shown in Fig. 6.7.

We assume a non-porous solid now.

This assumption will be relaxed later on.

Wellbore pressure adds compression on the wellbore wall

, and induces cavity expansion and tensile hoop stresses

, and induces cavity expansion and tensile hoop stresses

all around the wellbore.

all around the wellbore.

aligned with

aligned with

is shown in Fig. 6.8.

The deviatoric stress results in compression on the wellbore wall

is shown in Fig. 6.8.

The deviatoric stress results in compression on the wellbore wall

at

at

and

and  , and in tension

, and in tension

at

at

and

and  .

Hence, the presence of the wellbore amplifies compressive stresses 3 times

.

Hence, the presence of the wellbore amplifies compressive stresses 3 times

at

at

and

and  .

The variation of stresses around the wellbore depend on harmonic functions

.

The variation of stresses around the wellbore depend on harmonic functions

and

and

.

.

instead of

instead of  .

.

![\includegraphics[scale=0.55]{.././Figures/split/7-3.pdf}](img904.svg)

![\includegraphics[scale=0.65]{.././Figures/split/7-5.pdf}](img912.svg)

![$\displaystyle \left[

-(P_W - P_p) +3 \: \sigma_{Hmax} -\sigma_{hmin}

\right] = UCS + q \left[ P_W - P_p \right]$](img914.svg)

![\includegraphics[scale=0.50]{.././Figures/split/7-7.pdf}](img916.svg)

ft

ft psi/ft

psi/ft psi

psi

psi

psi psi

psi psi

psi

psi

psi psi

psi psi

psi

psi

psi

![\includegraphics[scale=0.65]{.././Figures/split/7-6.pdf}](img935.svg)

![$\displaystyle \left[ -(P_W - P_p) + (\sigma_{Hmax} + \sigma_{hmin})

- 2(\sigma_{Hmax} - \sigma_{hmin}) \cos (2 \theta_B) \right]

= UCS + q (P_W - P_p)$](img942.svg)

ppg

ppg

![$\displaystyle w_{BO} = 180^{\circ} - \arccos \left[ \frac{ 3220 \text{ psi} + 1...

...3220 \text{ psi} - 1220 \text{ psi})} \right] = 66 ^{\circ} \: \: \blacksquare

$](img949.svg)

![\includegraphics[scale=0.65]{.././Figures/split/7-8.pdf}](img950.svg)

![$\displaystyle S_{Hmax} = P_p + \frac{UCS + (1+q)(P_W - P_p)

- \sigma_{hmin} \left[ 1 + 2 \cos (\pi - w_{BO}) \right]}

{1 - 2 \cos (\pi - w_{BO})}$](img951.svg)

![\includegraphics[scale=0.65]{.././Figures/split/7-13.pdf}](img955.svg)

![$\sigma^{\Delta T} = [\alpha_T E/(1-\nu)] \Delta T$](img963.svg)

![\includegraphics[scale=0.65]{.././Figures/split/7-14.pdf}](img968.svg)

psi

psi psi

psi psi

psi psi

psi psi

psi

![\includegraphics[scale=0.65]{.././Figures/split/7-15.pdf}](img975.svg)

![\includegraphics[scale=0.65]{.././Figures/split/7-18.pdf}](img976.svg)

![\includegraphics[scale=0.45]{.././Figures/split/7-DevSurvey.pdf}](img982.svg)

![\includegraphics[scale=0.55]{.././Figures/split/8-ExampleDevWells.pdf}](img983.svg)

![\begin{displaymath}\uuline{S}{}_W =

\left[

\begin{array}{ccc}

S_{11} & S_{12} & ...

...2} & S_{23} \\

S_{31} & S_{32} & S_{33} \\

\end{array}\right]\end{displaymath}](img992.svg)

![\includegraphics[scale=0.65]{.././Figures/split/8-3.pdf}](img1003.svg)

![\includegraphics[scale=0.70]{.././Figures/split/8-BreakoutsDevWells.pdf}](img1008.svg)

![\includegraphics[scale=0.70]{.././Figures/split/8-BreakoutsDevWells-EXNF.pdf}](img1015.svg)

![\includegraphics[scale=0.70]{.././Figures/split/8-BreakoutsDevWells-EXRF.pdf}](img1018.svg)

, given principal stresses

, given principal stresses  and principal stress directions

and principal stress directions

.

.

), to explore deviation angle from 0 to 90 degrees.

), to explore deviation angle from 0 to 90 degrees.

) to explore azimuth from 0 to 360 degrees.

) to explore azimuth from 0 to 360 degrees.

, calculate stresses in the wellbore coordinate system

, calculate stresses in the wellbore coordinate system  , a function of

, a function of  .

.

, open a third loop (say counter

, open a third loop (say counter  ), to calculate stress at and around the wellbore wall for a cross section with angle from 0 to 360 degrees.

), to calculate stress at and around the wellbore wall for a cross section with angle from 0 to 360 degrees.

), analyze this data to output a quantity for each orientation (

), analyze this data to output a quantity for each orientation ( ). For example, you could count how many points are failing in shear and get from here the breakout angle.

). For example, you could count how many points are failing in shear and get from here the breakout angle.

![\includegraphics[scale=0.65]{.././Figures/split/8-TensfracsDevWells.pdf}](img1028.svg)

![\includegraphics[scale=0.75]{.././Figures/split/8-InterparticleDistance.pdf}](img1037.svg)

![\includegraphics[scale=0.65]{.././Figures/split/7-24.pdf}](img1039.svg)

and hoop

and hoop

stresses for a vertical well 8 in diameter in the directions of

stresses for a vertical well 8 in diameter in the directions of  (4,500 psi – acting E-W) and

(4,500 psi – acting E-W) and  (6,000 psi) up to 3 ft of distance considering that

(6,000 psi) up to 3 ft of distance considering that  = 3200 psi and

= 3200 psi and

= 3,200 psi

= 3,200 psi

= 4,000 psi

= 4,000 psi

,

,

) for

) for  and

and

as a function of distance (

as a function of distance ( ) from the center of the wellbore.

) from the center of the wellbore.

= 7,000 psi,

= 7,000 psi,  = 4,300 psi,

= 4,300 psi,  = 6,300 psi; Rock properties:

= 6,300 psi; Rock properties:  = 3,500 psi,

= 3,500 psi,  ,

,  = 800 psi).

= 800 psi).

, (ii)

, (ii)

(

(

), and (iii) for inducing tensile fractures (

), and (iii) for inducing tensile fractures ( ) for

) for

and

and

. Compare with

. Compare with

solved in class. How does the drilling mud window change with varying pore pressure?

solved in class. How does the drilling mud window change with varying pore pressure?

:

Consider the following problem, Wellbore: vertical; Site: onshore, 2 km of depth,

:

Consider the following problem, Wellbore: vertical; Site: onshore, 2 km of depth,

MPa/km,

MPa/km,

,

,

; Rock properties:

; Rock properties:  = 7 MPa,

= 7 MPa,  ,

,  = 2 MPa. Calculate wellbore pressure and corresponding mud weight for (i)

= 2 MPa. Calculate wellbore pressure and corresponding mud weight for (i)

, (ii)

, (ii)

, and (iii) for inducing tensile fractures for

, and (iii) for inducing tensile fractures for

?

?

,

,

. The rock properties are

. The rock properties are  = 7 MPa,

= 7 MPa,  ,

,  = 2 MPa. Calculate wellbore pressure and corresponding mud weight for (i)

= 2 MPa. Calculate wellbore pressure and corresponding mud weight for (i)

, (ii)

, (ii)

, and (iii) for inducing tensile fractures.

, and (iii) for inducing tensile fractures.

and another drilled parallel to

and another drilled parallel to  . Draw cross-sections of these two wells, identify involved stresses, and clearly mark expected positions of tensile fractures and wellbore breakouts.

. Draw cross-sections of these two wells, identify involved stresses, and clearly mark expected positions of tensile fractures and wellbore breakouts.

= 50 MPa,

= 50 MPa,  = 70 MPa,

= 70 MPa,

psi/ft and

psi/ft and

. The unconfined compressive strength of the rock is 8,500 psi, the rock internal friction coefficient is

. The unconfined compressive strength of the rock is 8,500 psi, the rock internal friction coefficient is  , and tensile strength is about

, and tensile strength is about  psi given the large density of natural fractures. Determine the mechanical stability limits on wellbore pressure for both horizontal well directions considered. Assume a breakout angle

psi given the large density of natural fractures. Determine the mechanical stability limits on wellbore pressure for both horizontal well directions considered. Assume a breakout angle

to calculate the lower bound for the mud window.

to calculate the lower bound for the mud window.