Subsections

Consider a 3D space with a given right-handed orthogonal coordinate system

,

,

,

,

in directions 1, 2 and 3 (Figure 3.2).

In a right-handed coordinate system, the first element of the base

in directions 1, 2 and 3 (Figure 3.2).

In a right-handed coordinate system, the first element of the base

is your index finger, the second element of the base

is your index finger, the second element of the base

is your middle finger, and the third element of the base

is your middle finger, and the third element of the base

is your thumb (all in your right hand).

is your thumb (all in your right hand).

The number that represents the value of a scalar (such as temperature  or pore pressure

or pore pressure  ) at a given point

) at a given point

is independent of the coordinate system orientation and origin (Figure 3.1).

However, the numbers that represent the value of a vector (such as velocity

is independent of the coordinate system orientation and origin (Figure 3.1).

However, the numbers that represent the value of a vector (such as velocity  or force

or force  ) or a tensor depend on the coordinate system.

A tensor, like stress, also depends on the coordinate system used to express its numerical values.

Read the values

) or a tensor depend on the coordinate system.

A tensor, like stress, also depends on the coordinate system used to express its numerical values.

Read the values  as the stress on face perpendicular to base vector

as the stress on face perpendicular to base vector

in the direction of base vector

in the direction of base vector

.

.

is positive if after a displacement

is positive if after a displacement  ,

,  points in opposite direction to

points in opposite direction to

(Figure 3.2).

(Figure 3.2).

Figure 3.1:

Examples of scalar, vector and tensor quantities in a shale reservoir.

|

All stresses  can be written as a matrix (Figure 3.2).

The diagonal terms correspond to normal stresses.

The off-diagonal terms correspond to shear stresses.

Off-diagonal stresses are symmetric

can be written as a matrix (Figure 3.2).

The diagonal terms correspond to normal stresses.

The off-diagonal terms correspond to shear stresses.

Off-diagonal stresses are symmetric

(

( ) because of angular momentum equilibrium (the element does not spin around any axis).

Hence, the stress tensor is symmetric with respect to the diagonal (top-left to bottom-right).

) because of angular momentum equilibrium (the element does not spin around any axis).

Hence, the stress tensor is symmetric with respect to the diagonal (top-left to bottom-right).

Figure 3.2:

Graphical and mathematical representation of the stress tensor. Read  as the stress on face perpendicular to

as the stress on face perpendicular to

in the direction

in the direction

.

.  is positive if after a positive displacement

is positive if after a positive displacement  ,

,  points in direction opposite to the directions of the base element

points in direction opposite to the directions of the base element

. All stresses in this figure have been drawn to be positive.

. All stresses in this figure have been drawn to be positive.

|

Since the stress tensor is symmetric and is composed by all real numbers, there exist 3 real-valued eigenvalues that we call principal stresses and denote

.

Each principal stress (eigenvalue) is associated with a principal direction (eigenvector).

Principal directions are always perpendicular to each other in a cartesian coordinate system.

When we write the stress tensor in the coordinate system aligned with directions of the principal stresses, the stress tensor results in diagonal elements populated by the principal stresses and zeros in the off-diagonal places.

Usually, the principal stresses are ordered from top to bottom starting with

.

Each principal stress (eigenvalue) is associated with a principal direction (eigenvector).

Principal directions are always perpendicular to each other in a cartesian coordinate system.

When we write the stress tensor in the coordinate system aligned with directions of the principal stresses, the stress tensor results in diagonal elements populated by the principal stresses and zeros in the off-diagonal places.

Usually, the principal stresses are ordered from top to bottom starting with  at the top (Figure 3.3).

at the top (Figure 3.3).

Figure 3.3:

Principal stresses and directions. Every tensor with non-zero off-diagonal terms can be simplified to a principal stress tensor with zero off-diagonal terms at the orientation that coincides with the directions of principal stresses.

|

EXAMPLE 3.1: For the following stress tensor obtained for the Neuquen Basin: a) calculate the eigenvalues (principal stresses), b) calculate eigenvectors (principal directions), c) answer what the stress regime is, and d) calculate the angle between the North and the direction of  in clockwise direction.

in clockwise direction.

![$\displaystyle \underset{=}{\sigma} =

\left[

\begin{array}{ccc}

\sigma_{NN} ...

...ccc}

8580 & 100 & 0 \\

100 & 9900 & 0 \\

0 & 0 & 9000

\end{array} \right]$](img288.svg)

psi

Note: The stress tensor is written in the North-East-Down coordinate system.

SOLUTION

First, find an appropiate math solver that can calculate eigenvalues and eigenvectors (Python, Matlab, Wolfram Alpha, etc.)

We will use Wolfram Alpha online in this solution.

Go to https://www.wolframalpha.com/ and enter:

eigenvalues

The answer to this querry is (click in “approximate forms”):

and

a,b) The principal stresses are

Figuring out what are horizontal and vertical stresses depends on the eigenvectors.

First, let's start with the easiest one.

Eigenvector

points straight in the downward direction, i.e., no horizontal component either in N or E directions (first two coordinates are zeros).

Hence,

points straight in the downward direction, i.e., no horizontal component either in N or E directions (first two coordinates are zeros).

Hence,

is in the vertical direction and is

is in the vertical direction and is  .

The other two (

.

The other two ( and

and  ) are the horizontal stresses, where

) are the horizontal stresses, where

and therefore

and therefore

.

.

c)  is the intermediate stress in this case, hence, this location is under strike-slip stress regime according to the Andersonian classification.

is the intermediate stress in this case, hence, this location is under strike-slip stress regime according to the Andersonian classification.

d) Eigenvector

gives the direction of

gives the direction of

.

Let's read the vector

.

Let's read the vector  according to the NED coordinate system: it goes North +0.0753277 units, it goes East +1.0 units, it goes Down 0.0 units.

Drawing this in a 3D coordinate system results in a vector in the NE horizontal plane pointing mostly towards the East.

The angle between the East axis and the vector is

according to the NED coordinate system: it goes North +0.0753277 units, it goes East +1.0 units, it goes Down 0.0 units.

Drawing this in a 3D coordinate system results in a vector in the NE horizontal plane pointing mostly towards the East.

The angle between the East axis and the vector is

rad

rad , i.e.,

, i.e.,

from the East axis towards the North axis.

Hence, the angle between the North and the vector

from the East axis towards the North axis.

Hence, the angle between the North and the vector  is

is

.

.

Equilibrium of stresses requires summation of forces in all directions to be zero when the object is not moving (no acceleration  , thus

, thus

).

Consider the schematic in Figure 3.4.

Summation of forces in direction 1, where the term

).

Consider the schematic in Figure 3.4.

Summation of forces in direction 1, where the term

is the body force component, proportional to the solid mass density

is the body force component, proportional to the solid mass density  and volume

and volume  , and the acceleration component

, and the acceleration component  , requires

, requires

which eventually reduces to the following equation when canceling terms and dividing by the element volume

|

(3.1) |

Figure 3.4:

Equilibrium of forces in direction 1.  ,

,

and

and

are applied on the non-visible faces of the solid element.

are applied on the non-visible faces of the solid element.

|

A generalization of equilibrium in all directions with all stresses (Figure 3.2) yields the Cauchy's equilibrium equations:

|

(3.2) |

Consider a half-space where the surface coincides with the origin of the coordinate system and gravity  points in direction 3, hence

points in direction 3, hence  in Eq. 3.2.

We assume infinite extension in directions 1 and 2, therefore there are no variations in directions 1 and 2, such that

in Eq. 3.2.

We assume infinite extension in directions 1 and 2, therefore there are no variations in directions 1 and 2, such that

.

Notice there are 6 unknowns and 3 equations in Eq. 3.2 (remember

.

Notice there are 6 unknowns and 3 equations in Eq. 3.2 (remember

).

The only equation we can solve is the third one.

Integration of the third equation yields the (vertical) stress

).

The only equation we can solve is the third one.

Integration of the third equation yields the (vertical) stress  ,

,

|

(3.3) |

equivalent to Eq. 2.11.

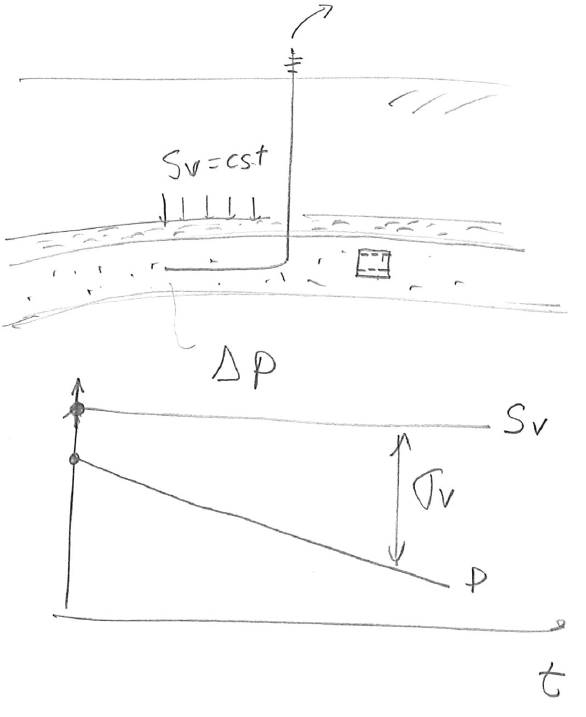

Figure 3.5:

Stress gradient in a solid half-space and derivation of total vertical stress  as a function of depth.

as a function of depth.

|

You may wonder “what about  and

and  ?

The horizontal stresses cannot be determined with the current equations.

The solution to this problem will be developed in section 3.3.4.

?

The horizontal stresses cannot be determined with the current equations.

The solution to this problem will be developed in section 3.3.4.

Figure 3.6 shows an example of an arbitrary shaped continuous solid subjected to external stresses  , external forces

, external forces  , body forces

, body forces  , and displacement constraints (bottom fixture).

As highlighted before, notice that there are 6 unknowns (9 unknowns if displacements are included) and 3 equations in Cauchy's equations of equilibrium (Eq. 3.2).

The solution of a general problem with arbitrary boundary conditions requires more equations to have a determined problem (as many equations as unknowns).

The solution of such problem requires knowledge of the material properties.

We need equations that relate displacement to stresses. These equations divide in two types:

, and displacement constraints (bottom fixture).

As highlighted before, notice that there are 6 unknowns (9 unknowns if displacements are included) and 3 equations in Cauchy's equations of equilibrium (Eq. 3.2).

The solution of a general problem with arbitrary boundary conditions requires more equations to have a determined problem (as many equations as unknowns).

The solution of such problem requires knowledge of the material properties.

We need equations that relate displacement to stresses. These equations divide in two types:

- kinematic equations, that relate displacements to strains, and

- constitutive equations, that relate strains to stresses.

The following section describes the simplest form of kinematic and constitutive equations.

Figure 3.6:

A general equilibrium problem. The solution of a general continuum mechanics problem requires knowledge of material properties and solid deformation.

|

Applications of stresses result in solid deformation and displacements.

Figure 3.7 shows an example of a solid body and the corresponding displacement vector field (traces the displacements from the original to the deformed state).

In this particular case, the solid is anchored at the bottom and deforms due to the application of a force (from left to right) on the top.

Hence, displacements at the bottom are zero and displacements on the top are the maximum.

Figure 3.7:

Example of displacement vector field for a solid anchored at the bottom and with a force (left to right) applied on the top. All other solid surfaces (but the bottom) can move freely. Strains are a function of the displacement field.

|

Yet, absolute displacements are not enough to determine stresses.

A solid may translate or rotate in space without development of any internal stresses required to equilibrate external actions (imagine a cookie “floating” in zero gravity within the International Space Station https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=q5uV4fTV0Zo).

Let's look at Figure 3.8 in order to relate displacements to strains:

- (LEFT) A solid is stretched on its face 1 (perpendicular to

) in direction 1 only. This type of deformation produces a change of volume of the solid and therefore contributes to volumetric strain. The resulting deformation or strain (change of length divided original length) is

) in direction 1 only. This type of deformation produces a change of volume of the solid and therefore contributes to volumetric strain. The resulting deformation or strain (change of length divided original length) is

|

(3.4) |

- (CENTER) A solid is stretched on its face 2 in direction 2 only. This type of deformation also contributes to volumetric strain. The resulting strain is

|

(3.5) |

- (RIGHT) The solid is now distorted. Notice that the faces do not make a right angle anymore. The change of volume is negligible for small deformations. The resulting distortion or shear strain is proportional to the change in angle between faces 1 and 2. Hence the change of angle is

![$\pi - \left[ \pi - \arctan(\Delta u_1 / \Delta x_2) + \arctan(\Delta u_2 / \Delta x_1) \right] $](img328.svg) . The shear strain is 1/2 of the total change of the angle and therefore (for small changes

. The shear strain is 1/2 of the total change of the angle and therefore (for small changes

)

)

|

(3.6) |

The average in the equation ensures capturing shear distortion rather than rotation.

Figure 3.8:

Strain equations for small deformations.

|

Strains do not quantify the absolute value of displacements, but its variation in space (derivative with respect to  ).

All other strains are found with similar equations in the 3D case.

Similarly to the stress tensor, strains can be organized in a tensor where elements in the diagonal contribute to volumetric strain, and off-diagonal elements are shear strains.

).

All other strains are found with similar equations in the 3D case.

Similarly to the stress tensor, strains can be organized in a tensor where elements in the diagonal contribute to volumetric strain, and off-diagonal elements are shear strains.

![\begin{displaymath}\underset{=}{\varepsilon} =

\left[

\begin{array}{ccc}

\cfrac{...

...n_{31} & \varepsilon_{32} & \varepsilon_{33}

\end{array}\right]\end{displaymath}](img333.svg) |

(3.7) |

The summation of all diagonal terms yields the volumetric strain

|

(3.8) |

EXAMPLE 3.2: Demonstrate the equality in Eq. 3.8 from simple geometrical concepts. Hint: the initial volume of the solid is

.

.

SOLUTION

The definition of volumetric strain is the ratio between the change of volume  and the initial volume

and the initial volume  :

:

For an elementary cubic volume with initial volume

and volume after deformation

and volume after deformation

, the equation above results

, the equation above results

Let us discard all the products containing

and also

and also

because they are much smaller than the other terms including just one

because they are much smaller than the other terms including just one

(

(

), then

), then

Constitutive equations tell us how a solid deforms (in time) as a response to stresses, to changes of temperature and to changes of pore pressure among others.

How to choose a constitutive equation depends on the material properties, the magnitude of strain changes, the magnitude of stresses, and the loading rate among other factors.

Figure 3.9:

Example of deformations imparted by an applied stress.

|

The simplest constitutive relationship for solids is linear elasticity, in which stresses and strains are linearly related by constant coefficients.

The examples in Figure 3.10 correspond to applications of linear elasticity in various dimensions:

Figure 3.10:

From Hooke's law to generalized 3D linear elasticity.

|

Consider a prismatic solid with length  to which we apply a stress

to which we apply a stress

on top face 3 (Figure 3.11).

The bottom face is not allowed to move in direction 3 but it can slide sideways.

The four other faces are free to move in all directions.

Notice that the top face can also deform in directions 1 and 2.

The Young modulus

on top face 3 (Figure 3.11).

The bottom face is not allowed to move in direction 3 but it can slide sideways.

The four other faces are free to move in all directions.

Notice that the top face can also deform in directions 1 and 2.

The Young modulus  is defined as the ratio between the applied stress

is defined as the ratio between the applied stress

and the resulting strain (in the direction of the applied stress)

and the resulting strain (in the direction of the applied stress)

|

(3.13) |

The solid will most likely tend to enlarge in the direction perpendicular to the stress applied.

The Poisson ratio (greek letter nu) is defined as (-1) times the ratio between the strain perpendicular to the applied stress

(or

(or

) and the strain in the direction of the applied stress

) and the strain in the direction of the applied stress

|

(3.14) |

These two coefficients are the two coefficients conventionally used as elasticity constants in continuum mechanics.

We will see later that in the subsurface we almost never find conditions of laterally “unconfined” stress loading like the one shown in Figure 3.11.

Figure 3.11:

Unconfined stress loading (compression) of a linear elastic isotropic solid. Because the solid is isotropic, the same equations are valid for compression in any other direction, and also in tension.

|

The real behavior of rocks differs from the linear elastic assumption.

Figure 3.12 shows a schematic representation of a typical unconfined loading test.

The figure plots axial stress  in the vertical axis and axial strain

in the vertical axis and axial strain

in the horizontal axis.

Often, rock plugs are not perfectly parallel or may have some microcracks.

Both features make the initial loading stress-strain behavior look less stiff than the actual rock stiffness.

After the initial loading, the rock may show a linear response -where the Young modulus is measured- followed by softening approaching rock failure and the peak stress.

When the test is performed under unconfined conditions, the peak stress is termed the “unconfined compressive strength (UCS)” of the rock (further explained in Section 4).

The Poisson ratio can be measured in the same range of the measurement of

in the horizontal axis.

Often, rock plugs are not perfectly parallel or may have some microcracks.

Both features make the initial loading stress-strain behavior look less stiff than the actual rock stiffness.

After the initial loading, the rock may show a linear response -where the Young modulus is measured- followed by softening approaching rock failure and the peak stress.

When the test is performed under unconfined conditions, the peak stress is termed the “unconfined compressive strength (UCS)” of the rock (further explained in Section 4).

The Poisson ratio can be measured in the same range of the measurement of  when lateral strain transducers are available.

when lateral strain transducers are available.

Figure 3.12:

Schematic of stress-strain curve during rock uniaxial loading in the laboratory.

|

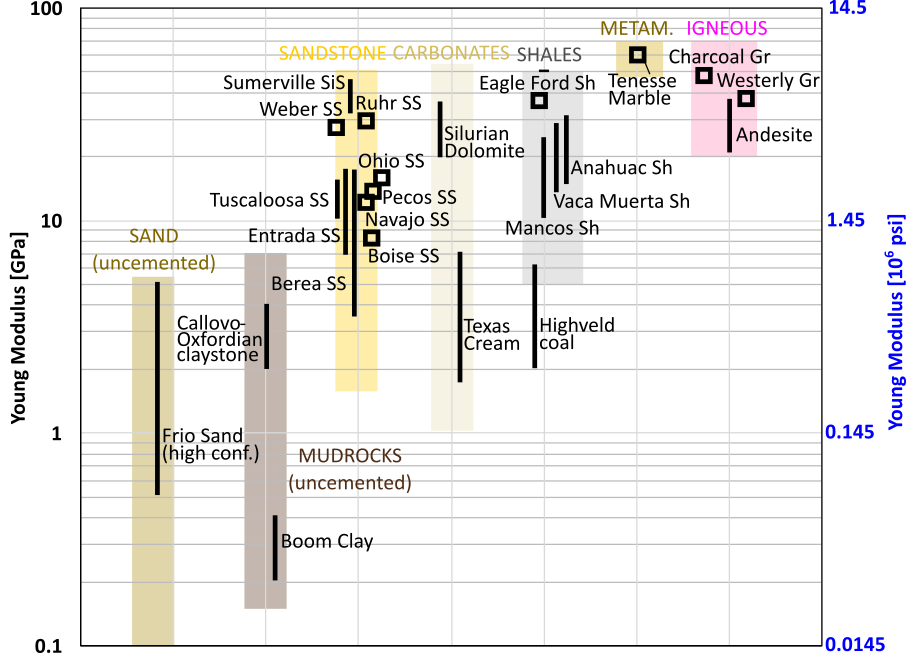

The Young modulus of sediments and rocks varies widely.

Figure 3.13 shows typical values of Young's modulus.

Figure 3.13:

Typical Young moduli for sediments and rocks. The values correspond to “quasi-static” loading from stress-strain response. SS: sandstone; SiS: Siltstone; Sh: Shale; Gr: Granite.

|

EXAMPLE 3.3: Compute the (axial) strain expected for a rock subjected to 3,000 psi of (axial) stress under unconfined axial loading for:

- A soft mudrock with E = 1 GPa

- A soft sandstone with E = 10 GPa

- A hard limestone with E = 50 GPa

SOLUTION

Let us work in SI units:

Then

GPa

GPa

GPa

Notice that rocks can be quite stiff and even for an effective stress as large as 3,000 psi (equivalent to a depth onshore of 5,000 ft under hydrostatic pore pressure), the deformation is in the order of 1% to 0.1% or less.

A generalization of the Young's modulus and Poisson's ratio equations (Eq. 3.13 and 3.14) in all directions leads to the 3 independent equations.

|

(3.15) |

In addition, shear strains

are proportional to the applied shear stress through shear modulus

are proportional to the applied shear stress through shear modulus

![$G=E/[2(1+\nu)]$](img381.svg) , such that,

, such that,

|

(3.16) |

Hence, all six equations permit putting together the shear strain tensor

as a function of the stress tensor

as a function of the stress tensor

through compliance fourth-order tensor

through compliance fourth-order tensor

.

.

|

(3.17) |

For ease of calculation, we will express the stress and strain tensors as

matrices, such that

matrices, such that

will be a

will be a

matrix.

This notation is called Voigt notation.

Hence, fourth-order tensor

matrix.

This notation is called Voigt notation.

Hence, fourth-order tensor

can be expressed as a

can be expressed as a

matrix:

matrix:

![\begin{displaymath}%compliance matrix

\left[

\begin{array}{c}

\varepsilon_{11} ...

...ma_{13} \cfrac{}{}\\

\sigma_{12} \cfrac{}{}

\end{array}\right]\end{displaymath}](img387.svg) |

(3.18) |

For example, let us apply a stress

![$\uuline{\sigma} = [0,0,\sigma_{33},0,0,0]^T$](img388.svg) as in example in Figure 3.11.

The result of

as in example in Figure 3.11.

The result of

is

is

which are the same strains we found above in the definition of  and

and  .

.

The inverse of the compliance matrix is the stiffness matrix

and let us calculate stress as a function of strain.

and let us calculate stress as a function of strain.

![\begin{displaymath}%stiffness matrix

\left[

\begin{array}{c}

\sigma_{11} \\

\s...

... \cfrac{}{}\\

2 \varepsilon_{12} \cfrac{}{}

\end{array}\right]\end{displaymath}](img393.svg) |

(3.19) |

Voigt notation is easier to code in computer codes that work with matrices.

The Lamé equations are the same equations shown above but use the Lamé parameters  and

and  instead of

instead of  and

and  .

For example, let us write the first equation of the product of the stiffness tensor and the strain tensor in Voigt notation:

.

For example, let us write the first equation of the product of the stiffness tensor and the strain tensor in Voigt notation:

or equivalently

where the Lamé parameters are:

|

(3.20) |

and

|

(3.21) |

Notice that  , the shear modulus as defined above.

Putting equations in all directions together yields the complete set of Lamé's equations:

, the shear modulus as defined above.

Putting equations in all directions together yields the complete set of Lamé's equations:

|

(3.22) |

EXAMPLE 3.4: Write the Lamé equations (Eq. 3.22) in matrix format using the Voigt notation.

SOLUTION

Remember that there are only two independent constitutive parameters in linear isotropic elasticity.

The usual pair choice is  and

and  .

However, there are other options depending on the application and equations used, e.g,

.

However, there are other options depending on the application and equations used, e.g,  and

and  .

A complete list of parameter pairs is available scrolling to the bottom in https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Young's_modulus.

Figure 3.14 list the most common equivalencies.

.

A complete list of parameter pairs is available scrolling to the bottom in https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Young's_modulus.

Figure 3.14 list the most common equivalencies.

Figure 3.14:

Table with equivalencies of the most used elastic moduli in linear isotropic elasticity.

|

Porous solids deform and fail due to the application of effective stresses rather than total stress.

Hence, Hooke's law requires to use the effective stress tensor rather than the total stress tensor.

The equation

is incorrect.

Instead, the stress-strain relationship requires effective stress:

is incorrect.

Instead, the stress-strain relationship requires effective stress:

|

(3.23) |

Pore pressure has an effect on normal stresses only (fluid pressure would not be able to cause solid shear strains). Hence, only pore pressure is subtracted from the diagonal terms of the total stress tensor.

The subtracted value is the same in all directions because pore pressure is the same in all directions at a given point location.

Figure 3.15:

The effective stress tensor.

|

Rigorously, the effective stress tensor needs a correction of pore pressure by the Biot coefficient  that accounts for solid grain deformation with changes in pore pressure.

that accounts for solid grain deformation with changes in pore pressure.

|

(3.24) |

For most problems, the assumption of

is satisfactory.

The rock matrix of tight sandstones and shales may have a Biot coeffiecient as low as

is satisfactory.

The rock matrix of tight sandstones and shales may have a Biot coeffiecient as low as

.

The theory of poroelasticity is covered in the “Advanced Geomechanics” course with a brief introduction in Section 3.7.1.

.

The theory of poroelasticity is covered in the “Advanced Geomechanics” course with a brief introduction in Section 3.7.1.

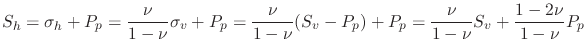

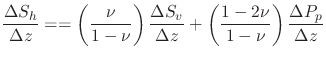

3.3.4 Calculation of horizontal stress according to linear elasticity

Let us revisit the problem of stress calculation in a half-space, such as the Earth's shallow subsurface.

We already know that the vertical total stress (

) is a function of depth and rock bulk mass density.

) is a function of depth and rock bulk mass density.

|

(3.25) |

The effective vertical stress will be

|

(3.26) |

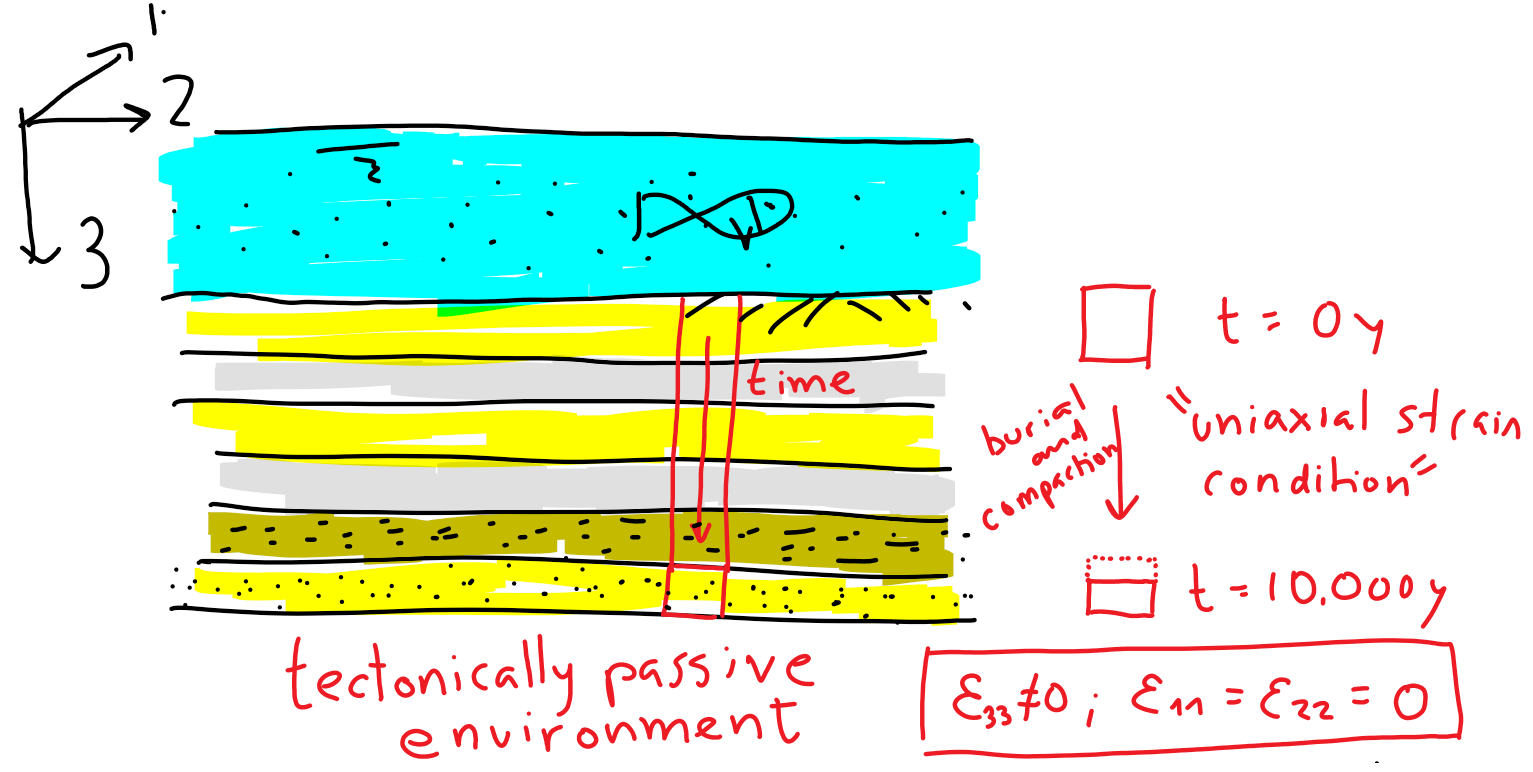

Let us now assume that the half space did not deform in horizontal directions (

), usually known as a “tectonically passive environment”. This means that the solid is laterally contained at “repose” and no additional horizontal strains have been added either compressive or tensile.

Such is the case of a sedimentary basin with no additional tectonic strains.

), usually known as a “tectonically passive environment”. This means that the solid is laterally contained at “repose” and no additional horizontal strains have been added either compressive or tensile.

Such is the case of a sedimentary basin with no additional tectonic strains.

Figure 3.16:

Uniaxial strain condition with sedimentation in a tectonically passive environment. As sediment burial progresses the sediment compacts only in vertical direction.

|

Let us now use Equation 3.23 together with the equilibrium equation.

Shear strains are zero.

Hence

![$\uuline{\varepsilon} = [0,0,\varepsilon_{33},0,0,0]^T$](img414.svg) .

Then, the multiplication of

.

Then, the multiplication of

, results in

, results in

|

(3.27) |

Let us express

as a function of

as a function of

, and plug it in the equation for horizontal stresses

, and plug it in the equation for horizontal stresses

and

and

.

The result is

.

The result is

|

(3.28) |

or equivalently

|

(3.29) |

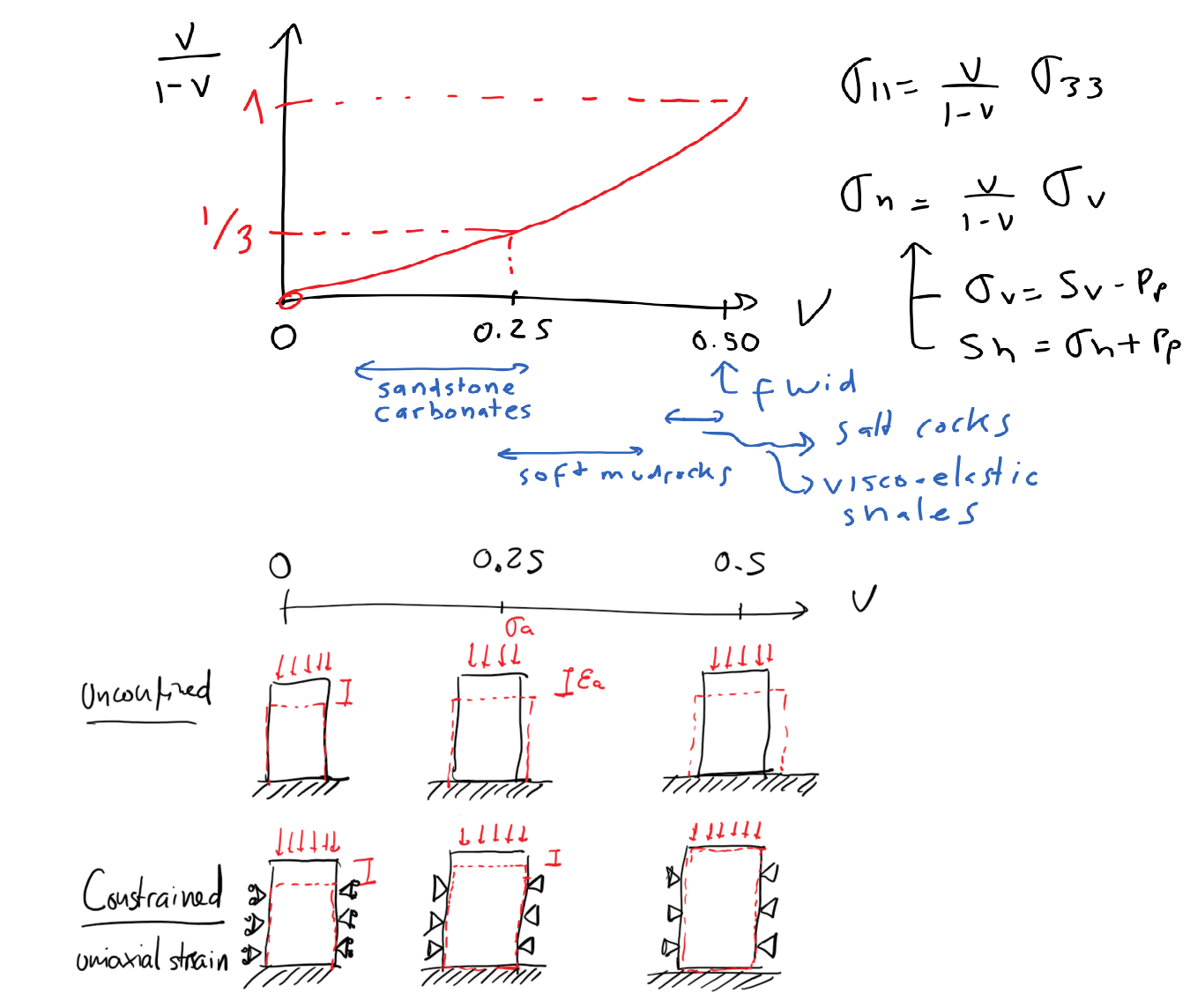

For typical values of

, the horizontal stress coefficient is

, the horizontal stress coefficient is

(Figure 3.17).

Thus, the effective horizontal stress is approximately one third of the effective vertical stress.

Contrary to a fluid, the solid does not push sideways with all its weight.

It pushes sideways with just a fraction of its weight proportionally to its tendency to deform sideways, i.e., the Poisson ratio.

Notice that

(Figure 3.17).

Thus, the effective horizontal stress is approximately one third of the effective vertical stress.

Contrary to a fluid, the solid does not push sideways with all its weight.

It pushes sideways with just a fraction of its weight proportionally to its tendency to deform sideways, i.e., the Poisson ratio.

Notice that

implies

implies

.

An “effective”

.

An “effective”

is applicable for fluids, soft rocks under undrained loading, and salt rocks.

is applicable for fluids, soft rocks under undrained loading, and salt rocks.

Figure 3.17:

Lateral stress coefficient as a function of Poisson's ratio. Solids do not push sideways with all its weight when compacted vertically.

|

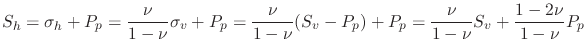

The total horizontal stresses are obtained by adding pore pressure to the effective horizontal stresses:

and

and

.

.

Equation 3.29 allows us to approximate a lower bound for the fracture gradient, that is, the pressure required to open a hydraulic fracture.

Such pressure will be equal or greater than the minimum horizontal total stress  (assuming zero tectonic strains):

(assuming zero tectonic strains):

|

(3.30) |

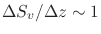

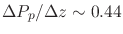

The gradient is the variation of pressure (or stress) with depth, i.e., derivative with respect to depth  .

Assuming that the material properties are constant, then,

.

Assuming that the material properties are constant, then,

|

(3.31) |

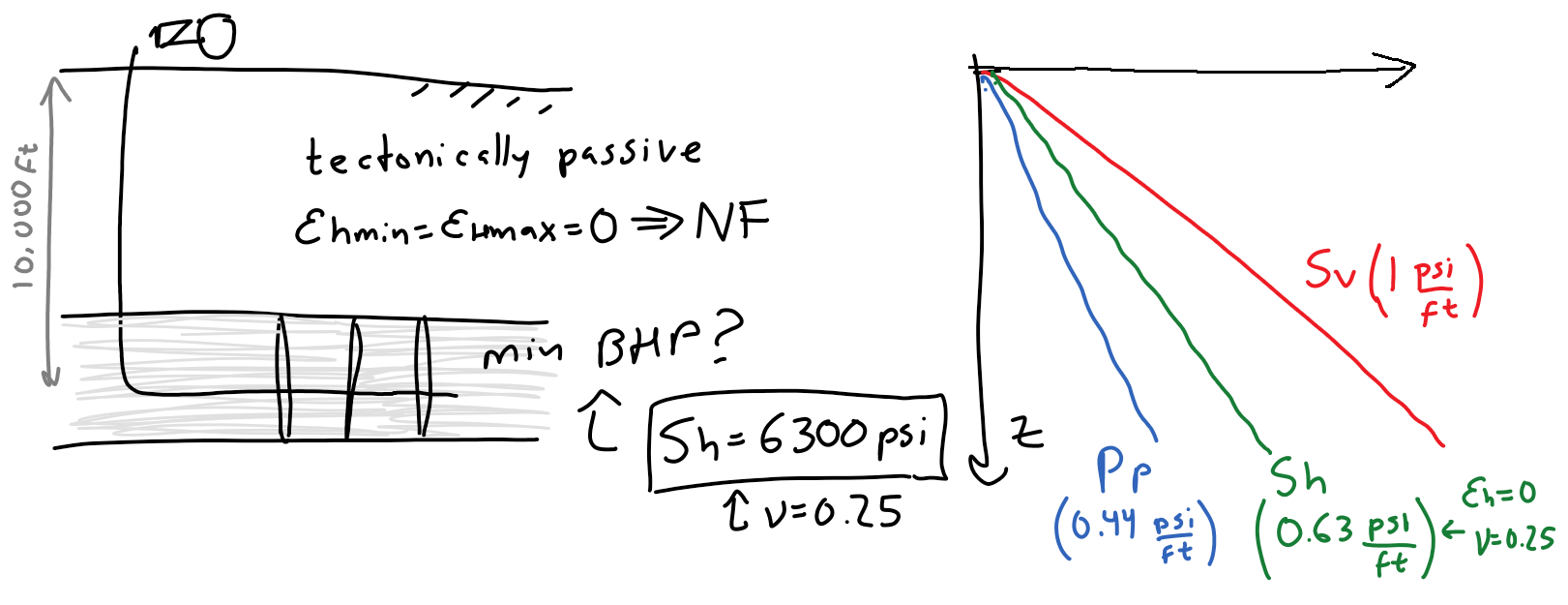

For example, for onshore conditions with typical values

psi/ft,

psi/ft,

psi/ft, and

psi/ft, and

, the fracture gradient is

, the fracture gradient is

psi/ft. Figure XX shows a schematic example of the calculated fracture gradient.

psi/ft. Figure XX shows a schematic example of the calculated fracture gradient.

Figure 3.18:

Schematic representation of the prediction of minimum horizontal total stress  , a lower bound for the fracture gradient, using Eq. 3.31

, a lower bound for the fracture gradient, using Eq. 3.31

|

Let us now relax the assumption of horizontal strains equal to zero, such that they are not zero

, but are known quantities.

We use the equation

, but are known quantities.

We use the equation

again. Shear strains are zero.

Hence

again. Shear strains are zero.

Hence

![$\uuline{\varepsilon} = [\varepsilon_{11},\varepsilon_{22},\varepsilon_{33},0,0,0]^T$](img430.svg) .

The resulting equations are,

.

The resulting equations are,

|

(3.32) |

Let us now substitute

in the equations of

in the equations of

and

and

as a function of

as a function of

. The result is:

. The result is:

|

(3.33) |

Horizontal strains are usually caused by tectonic plate movement.

Hence, we can call them “tectonic strains” and say that this is a “tectonically active” environment, particularly for large compressive horizontal strains that may increase horizontal stress over the vertical stress.

Let us call

the maximum (compressive) tectonic strain, and

the maximum (compressive) tectonic strain, and

the minimum tectonic strain in a given direction.

As a result the maximum effective horizontal stress and minimum horizontal stresses are:

the minimum tectonic strain in a given direction.

As a result the maximum effective horizontal stress and minimum horizontal stresses are:

|

(3.34) |

where

is called the plane strain modulus.

We will see later that the plane strain modulus, rather than the Young's modulus, appears in many of the equations of interest to subsurface applications.

These equations have been coded in a Jupyter notebook available at https://mybinder.org/v2/gh/dnicolasespinoza/GeomechanicsJupyter/master?filepath=HorizontalStresses_Widget.ipynb.

The above algorithm further assumes a linear increase of strain with depth.

is called the plane strain modulus.

We will see later that the plane strain modulus, rather than the Young's modulus, appears in many of the equations of interest to subsurface applications.

These equations have been coded in a Jupyter notebook available at https://mybinder.org/v2/gh/dnicolasespinoza/GeomechanicsJupyter/master?filepath=HorizontalStresses_Widget.ipynb.

The above algorithm further assumes a linear increase of strain with depth.

The following workflow is valid to calculate horizontal total stress with any constitutive (rock property) model:

- Calculate total vertical stress

- Calculate pore pressure

.

.

- If hydrostatic, use

psi/ft.

psi/ft.

- If non-hydrostatic, use the method based on shale porosity

or use directly

or use directly

if

if  is given.

is given.

- Calculate effective vertical stress:

- Calculate effective horizontal stresses

and

and

:

:

- Assuming linear isotropic elasticity, use Eq. 3.34 if tectonic strains are not zero or simply Eq. 3.29 if tectonic strains are zero.

- Assuming subsurface stresses are at yield, use Eqs. in the Chapter about “Stresses on Faults”.

- Assuming subsurface stresses are affected by visco-elastic response, add stress relaxation component (Fig. 3.26)

- Calculate total horizontal stress by adding pore pressure to effective horizontal stresses:

and

EXAMPLE 3.5:

Calculate the total horizontal stresses in a section of the Barnett Shale located at 7,950 ft (TVD) using the theory of linear elasticity.

Assume a constant vertical stress gradient

MPa/km, overpressure parameter

MPa/km, overpressure parameter

, shale Young's modulus

, shale Young's modulus

psi, Poisson's ratio

psi, Poisson's ratio

, and tectonic strains

, and tectonic strains

and

and

.

.

SOLUTION

At a depth of 7950 ft

Hence, the effective vertical stress is

Now, we are in conditions of using Eq. 3.34.

Let us first calculate the plane strain modulus:

Then,

Finally, let us compute the total horizontal stresses by adding pore pressure:

Horizontal stresses tend to be different in most basins, hence,

.

In practice, differences

.

In practice, differences

MPa (100 psi) tend to be enough to force hydraulic fractures to grow mostly perpendicular to

MPa (100 psi) tend to be enough to force hydraulic fractures to grow mostly perpendicular to  in places subjected to normal faulting or strike slip stress regime.

Locations with small horizontal stress anisotropy (mostly normal faulting sites) impose less control on orientations of hydraulic fractures (Chapter 7) and on orientation of faults (Chapter 5).

Polygonal faults (Chapter 5 - [update link]) are an example of normal fault growth with strike in all directions because

in places subjected to normal faulting or strike slip stress regime.

Locations with small horizontal stress anisotropy (mostly normal faulting sites) impose less control on orientations of hydraulic fractures (Chapter 7) and on orientation of faults (Chapter 5).

Polygonal faults (Chapter 5 - [update link]) are an example of normal fault growth with strike in all directions because

.

.

3.3.5 Calculation of reservoir compressibility with linear elasticity

The rock pore volume compressibility  is a critical parameter in the fluid flow mass conservation equation and therefore on the diffusivity equation (1D example):

is a critical parameter in the fluid flow mass conservation equation and therefore on the diffusivity equation (1D example):

|

(3.35) |

Where the total compressibility is

.

Reservoir simulators usually calculate the fluid compressibility

.

Reservoir simulators usually calculate the fluid compressibility

based in phase behavior, hence, the only required input is

based in phase behavior, hence, the only required input is  .

For example, compaction drive is proportional to rock compressibility (see https://petrowiki.org/Compaction_drive_reservoirs).

.

For example, compaction drive is proportional to rock compressibility (see https://petrowiki.org/Compaction_drive_reservoirs).

The pore volume compressibility  tells us what the change of pore volume

tells us what the change of pore volume  is due to a change in pore pressure:

is due to a change in pore pressure:

|

(3.36) |

The equation above captures reservoir boundary conditions in which the total vertical stress  remains constant (overburden above the reservoir does not change) and there is no change of lateral strain

remains constant (overburden above the reservoir does not change) and there is no change of lateral strain

, a condition also termed as “uniaxial strain” deformation.

Such condition is appropriate in long and thin reservoirs with a compliant caprock (Figure 3.19).

, a condition also termed as “uniaxial strain” deformation.

Such condition is appropriate in long and thin reservoirs with a compliant caprock (Figure 3.19).

The measurements of  are derived from bulk volume measurements.

Let us assume that the change of pore volume

are derived from bulk volume measurements.

Let us assume that the change of pore volume

is equal to the change of bulk volume

is equal to the change of bulk volume

, which means that all bulk deformation is caused by change of porosity.

Hence it is possible to rewrite the definition of

, which means that all bulk deformation is caused by change of porosity.

Hence it is possible to rewrite the definition of  as

as

|

(3.37) |

Porosity is defined as

and the term between parenthesis is defined as the bulk compressibility under uniaxial condition

and the term between parenthesis is defined as the bulk compressibility under uniaxial condition  (notice

(notice

).

Hence, the parameter

).

Hence, the parameter  is linked to the bulk rock compressibility

is linked to the bulk rock compressibility  through porosity:

through porosity:

|

(3.38) |

where the bulk compressibility with no lateral strain is approximately equal to the inverse of the bulk constrained modulus

, where

, where

![$M = (1-\nu) E / [(1+\nu)(1-2\nu)]$](img468.svg) for an isotropic elastic solid.

The approximation is due to a correction needed to account for grain compressibility.

Finally, we can calculate the uniaxial strain pore compressibility using the typical mechanical parameters

for an isotropic elastic solid.

The approximation is due to a correction needed to account for grain compressibility.

Finally, we can calculate the uniaxial strain pore compressibility using the typical mechanical parameters  and

and  as,

as,

. . |

(3.39) |

Figure 3.19:

Pressure depletion causes reservoir compaction. The reservoir compressibility is inversely proportional to the constrained modulus  .

.

|

Unfortunately, the theory of linear elasticity is quite limited to capture the visco-elasto-plastic behavior of rocks upon depletion during long times and with large strains.

Hence, Eq. 3.39 is just a first order approximation.

Typical values of pore volume compressibility vary from 2 to 30

psi

psi , where

, where

psi

psi sip.

Stiff well cemented rocks have low pore volume compressibility

sip.

Stiff well cemented rocks have low pore volume compressibility

sip while uncemented loose sediments tend to have high pore volume compressibility

sip while uncemented loose sediments tend to have high pore volume compressibility

sip.

sip.

EXAMPLE 3.6: Calculate the pore compressibility of a rock tested in the laboratory with porosity

, Young's modulus

, Young's modulus  GPa, and

GPa, and

. Provide the solution in [

. Provide the solution in [ psi]

psi] units.

units.

SOLUTION

The constrained modulus is

Hence,

The general solution of a linear elasticity problem requires combining the equilibrium, kinematic, and constitutive equations.

The result is a differential equation with displacement  as the unknown:

as the unknown:

|

(3.40) |

where

![$\lambda = (\nu E)/[(1+\nu)(1-2\nu)]$](img481.svg) is the first Lamé parameter,

is the first Lamé parameter,  is the shear modulus,

is the shear modulus,  is the rock bulk mass density, and

is the rock bulk mass density, and  is the body force acceleration vector (usually gravity).

A review of the gradient

is the body force acceleration vector (usually gravity).

A review of the gradient  , divergence

, divergence

and Laplacian

and Laplacian

operators is available at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vector_calculus_identities.

In summary, these are all derivatives that quantify changes of displacement in space.

The full derivation of this equation can be found here: https://youtu.be/1PnQ10H2vV0.

operators is available at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vector_calculus_identities.

In summary, these are all derivatives that quantify changes of displacement in space.

The full derivation of this equation can be found here: https://youtu.be/1PnQ10H2vV0.

The solution requires knowledge of the domain geometry, boundary conditions and initial conditions.

For example, a hydraulic fracture simulator solves numerically these same equations (Figure 3.20).

In this class, we will see analytical solutions of this equation for 1) displacements and stresses around wellbores, and 2) displacements and stresses around planar fractures.

Figure 3.20:

General continuum mechanics problem.

|

Real rocks are not isotropic due to layering, particle orientation during deposition, and fracturing.

Sedimentary rocks are usually well explained with transverse isotropic symmetry.

Vertical transverse isotropy assumes symmetry around a vertical axis such that mechanical properties are the same when measured along any direction in a horizontal plane but different in the vertical direction (the direction perpendicular to bedding).

The presence of vertical fractures in a preferred orientation can break this symmetry and make the medium orthorhombic.

Accurate determination of horizontal stresses with elastic models (e.g., Eq. 3.34) may need anisotropic models to properly account for rock stiffness anisotropy.

Figure 3.21:

Stiffness matrix coefficients in anisotropic media.

|

Most sedimentary rocks are stiffer in the horizontal direction than in the vertical direction  .

.

Figure 3.22:

Stiffness parallel and perpendicular to bedding. [add real data]

|

Most rocks will exhibit permanent (plastic) deformation when loaded at large strains

.

Plastic deformation includes plastic compression strains and plastic shear strains.

The theory of elasto-plasticity is covered in the Advanced Geomechanics course https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLv0npDbE5HXssC2CwCAssJs0fTkKquQFj.

Figure 3.23 shows an example of permanent deformation during a typical deviatoric loading test to measure Young's modulus.

First-time loading usually involves plastic deformation and creep.

Therefore the loading Young's modulus

.

Plastic deformation includes plastic compression strains and plastic shear strains.

The theory of elasto-plasticity is covered in the Advanced Geomechanics course https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLv0npDbE5HXssC2CwCAssJs0fTkKquQFj.

Figure 3.23 shows an example of permanent deformation during a typical deviatoric loading test to measure Young's modulus.

First-time loading usually involves plastic deformation and creep.

Therefore the loading Young's modulus  results smaller than the unloading modulus

results smaller than the unloading modulus

.

While

.

While  calculation lumps elastic, plastic, and creep strains,

calculation lumps elastic, plastic, and creep strains,

involves mostly elastic strains.

Notice the the re-loading modulus is similar to the unloading modulus

involves mostly elastic strains.

Notice the the re-loading modulus is similar to the unloading modulus

because a re-loading path is not a first-time loading.

because a re-loading path is not a first-time loading.

Figure 3.23:

Loading and unloading stress paths for a shale sample. Two unloading-reloading paths were performed before rock failure. Notice that

because of plastic and creep strains.

because of plastic and creep strains.

|

So far, we have assumed that rock strain-stress response is independent of loading rate, however, this is not true.

The stiffness of rocks is not the same if loaded in a time frame of thousands of years (geological time), years (reservoir production time), or during a few minutes (drilling and laboratory time).

Rocks tend to be softer and more ductile as the loading time frame increases.

Figure 3.24:

Strain-rate dependent stiffness. [Put your own data]

|

Another manifestation of visco-elasticity is time-dependent deformation, usually known as “creep”.

Whenever a change of stress is applied and set constant, deformations may continue with time.

An example of this type of response is when drilling through salt rocks.

Stresses intensify around the wellbore after the hole is bored.

The wellbore walls will deform if left uncased and stick to the drilling string.

Figure 3.25:

Time-dependent deformation: Creep.

|

One other manifestation of visco-elasticity is time-dependent stress change or stress relaxation.

Whenever a change of strain is applied and set constant, stresses may relax with time.

For example, unconsolidated sands may relax horizontal stresses with time after a tectonic strain is applied (Figure 3.27).

Therefore, neglecting visco-elasticity may result in an overestimation of horizontal stresses in unconsolidated sands with a purely elastic model.

Figure 3.26:

Time-dependent deformation: stress relaxation.

|

Figure 3.27:

Impact of stress relaxation in horizontal stresses in the subsurface. (a) Decrease of  due to deviatoric stress relaxation caused by a paleo-tectonic strain

due to deviatoric stress relaxation caused by a paleo-tectonic strain

. (b)Increase of

. (b)Increase of  due to deviatoric stress relaxation caused by overburden stress.

due to deviatoric stress relaxation caused by overburden stress.

|

3.7.1 Poro-elasticity

When rocks deform, most of the deformation transfers into changes of porosity.

As a matter of fact, the solid phase can also deform and change volume.

In that case the equation that links stresses and deformations

needs to be corrected according to Biot's effective stress:

needs to be corrected according to Biot's effective stress:

|

(3.41) |

where  is the Biot coefficient and

is the Biot coefficient and

is the identity tensor.

In the case of linear elastic and isotropic porous media, the Biot coefficient is:

is the identity tensor.

In the case of linear elastic and isotropic porous media, the Biot coefficient is:

|

(3.42) |

where

is the drained bulk modulus of the porous solid and

is the drained bulk modulus of the porous solid and  is the unjacketed bulk modulus.

The unjacketed bulk modulus is equal to the mineral bulk modulus

is the unjacketed bulk modulus.

The unjacketed bulk modulus is equal to the mineral bulk modulus

when all porosity is connected and the rock has a mono-mineral composition.

The values of the Biot coefficient range from the value of porosity to 1.

Most rocks and sediments subjected to large depths have a Biot coefficient that ranges from

when all porosity is connected and the rock has a mono-mineral composition.

The values of the Biot coefficient range from the value of porosity to 1.

Most rocks and sediments subjected to large depths have a Biot coefficient that ranges from  0.4 to 0.95, decreasing in value as rocks get stiffer.

In anisotropic media, the poroelasticity correction factor becomes a tensor

0.4 to 0.95, decreasing in value as rocks get stiffer.

In anisotropic media, the poroelasticity correction factor becomes a tensor

.

The corrections for poroelasticity

.

The corrections for poroelasticity

become significant in tight rocks with high stiffness, and low and unconnected porosity.

become significant in tight rocks with high stiffness, and low and unconnected porosity.

3.7.2 Thermo-elasticity

Changes of temperature in solids change the equilibrium distance between molecules, and therefore induce strains.

Imagine a solid heated up, but not allowed to dilate in vertical direction (Figure 3.28).

The result is an increase of stress in vertical direction rather than a deformation in vertical direction.

Figure 3.28:

Thermo-elasticity example of dilation thermal stress.

|

The coefficient of thermal dilation  quantifies strains as a function of changes of temperature

quantifies strains as a function of changes of temperature  at constant pressure

at constant pressure  , and it is defined as

, and it is defined as

|

(3.43) |

Typical linear thermal dilation coefficients of rock range from 5 to 10

1/C

1/C .

You may compare this range to the linear thermal dilation coefficient of steel

.

You may compare this range to the linear thermal dilation coefficient of steel

1/C

1/C and water

and water

1/C

1/C .

.

Under unconstrained (displacement) conditions, a negative change in temperature causes shrinkage and a positive change in temperature causes dilation.

The elastic equations extended to consider thermal changes make explicit that stresses can be changed as a result of a change in temperature  and/or as a result of a change of volumetric strains.

and/or as a result of a change of volumetric strains.

|

(3.44) |

Eq. 3.44 does not include the effects of pore pressure.

The coupled thermo-poro-elastic equations are covered in the Advanced Geomechanics course.

Thermal(-induced) stresses can cause reductions in fracture gradient when drilling with relatively cold drilling mud.

Thermal(-induced) stresses can also cause enhanced fractured reactivation when injecting cold fluids in a hot reservoir, such as in deep geothermal energy recovery.

EXAMPLE 3.7: Derive an expression of the thermal swelling stress (in vertical direction) for the example shown in Figure 3.28.

SOLUTION

Let us assume the axis 3 in the vertical direction, then

,

,

,

,

.

Then, for

.

Then, for

, a simplification of Eq. 3.44 results in,

, a simplification of Eq. 3.44 results in,

Solving for

and pluging it the

and pluging it the

equation results in

equation results in

- For the following stress tensors: a) calculate the eigenvalues (principal stresses), b) calculate eigenvectors (principal directions), c) answer what the stress regime is, and d) calculate the angle between the North and the direction of

in clockwise direction:

in clockwise direction:

- North Colorado:

![\begin{displaymath}\underset{=}{\sigma} =

\left[

\begin{array}{ccc}

\sigma_{NN} ...

...-200 & 7300 & 0 \\

0 & 0 & 8100

\end{array} \right] \text{psi}\end{displaymath}](img520.svg) |

(3.45) |

- North-East North Dakota:

![\begin{displaymath}\underset{=}{\sigma} =

\left[

\begin{array}{ccc}

\sigma_{NN} ...

...

100 & 6300 & 0 \\

0 & 0 & 6200

\end{array} \right] \text{psi}\end{displaymath}](img521.svg) |

(3.46) |

Notes: Compare your solutions with expectations of the US stress map (https://www.usgs.gov/media/images/new-us-stress-map). You may use Python, Matlab, Wolfram Alpha (https://www.wolframalpha.com/), or a calculator that supports linear algebra to solve this problem.

- Draw the normal and shear stresses defined as positive on the four sides of the following square solid element according to the given 2D coordinate system.

- An axial deviatoric test was performed in an organic-rich Mancos shale sample. The sample was cored in the direction of bedding. The sample diameter was

in and the sample length was

in and the sample length was  in. The test was conducted in “as received conditions”. The data is available here.

The data contains Time (s), Axial force

in. The test was conducted in “as received conditions”. The data is available here.

The data contains Time (s), Axial force  (lb), Axial displacement

(lb), Axial displacement  (in), and Radial displacement

(in), and Radial displacement  (in).

(in).

- Calculate the axial stress as a function of axial force

, where

, where  is the cross-sectional area.

is the cross-sectional area.

- Calculate axial and radial strains utilizing the displacements

(

( ) and

) and  (

( ). Notice the radial strain is

). Notice the radial strain is

. Calculate the volumetric strain as well.

. Calculate the volumetric strain as well.

- Show the solution of the first and second point in the same graph, plot: (i) axial stress versus axial strain, (ii) axial stress versus radial strain, and (iii) axial stress versus volumetric strain. (Plot axial stress in the vertical axis.)

- Utilizing linear curve fitting, compute Young's modulus and Poisson's ratio in the interval of axial strain between 0.0028 and 0.0040. You may need to plot radial strain versus axial strain to calculate the Poisson's ratio (using a linear regression).

- Isotropic loading means that applied stresses are the same in all directions.

- Using the equations of 3D linear elasticity (

in Voigt notation) show that by applying an isotropic stress

in Voigt notation) show that by applying an isotropic stress

(no shear) the volumetric strain is equal to

(no shear) the volumetric strain is equal to

.

.

- What would be the volumetric strain

, for a shale rock with

, for a shale rock with

psi and

psi and  , when subjected to an isotropic change of stress

, when subjected to an isotropic change of stress

3,000 psi? Write the full (3D) acting stress tensors and resulting strain tensor as matrices 3

3,000 psi? Write the full (3D) acting stress tensors and resulting strain tensor as matrices 3  3.

3.

- What is the shale bulk modulus

?

?

- One-dimensional strain loading implies changes of stress with changes in strain in only one direction (usually the vertical direction).

- Using the equations of 3D linear elasticity (

in Voigt notation) show that by applying stress in one direction (say 1) and not letting the solid expand in the other two, you can recover the following expression

in Voigt notation) show that by applying stress in one direction (say 1) and not letting the solid expand in the other two, you can recover the following expression

.

.

- The proportionality coefficient in the equation above is called the constrained modulus

. Is it lower or higher than E? What is the physical explanation?

. Is it lower or higher than E? What is the physical explanation?

- A high porosity carbonate reservoir is subjected to depletion and a change of effective vertical stress of 20 MPa. The carbonate rock Young's modulus is 1.5 GPa and Poisson's ratio is 0.10. What are the resulting strain and stress tensors due to compaction? Write the results as

matrices.

matrices.

- What are the bulk and pore compressibilities of this carbonate rock if

. Provide answers in

. Provide answers in  sip.

sip.

- The top of the Barnett shale is located at about 7,950 ft TVD. At this depth:

- Compute the total vertical stress assuming a lithostatic gradient of 23.8 MPa/km.

- Compute the effective vertical stress assuming hydrostatic pore pressure gradient.

- Compute horizontal effective stresses assuming linear isotropic elasticity,

=0.22 and that horizontal strains are nearly zero.

=0.22 and that horizontal strains are nearly zero.

- Write the tensor of effective stresses as a matrix.

- Compute total horizontal stress.

- Compute the ratio between effective horizontal stress and effective vertical stress.

- Compute the ratio between total horizontal stress and total vertical stress.

- Compute effective and total stresses assuming there is overpressure with

, tectonic strains are

, tectonic strains are

and

and

, and the shale Young’s modulus is

, and the shale Young’s modulus is

psi.

psi.

You may use the python code available in the following link at Google Colab: https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/1rIzjFd5p81JGOSRUkaMiQF018idb1XU3?usp=sharing.

I suggest you use it as “inspiration” and learning, but write your own.

Make sure to acknowledge any copying and pasting.

- Fjaer, E., Holt, R.M., Raaen, A.M., Risnes, R. and Horsrud, P., 2008. Petroleum related rock mechanics (Vol. 53). Elsevier. (Chapter 1)

- Jaeger, J.C., Cook, N.G. and Zimmerman, R., 2009. Fundamentals of rock mechanics. John Wiley & Sons. (Chapter 5)

![\includegraphics[scale=0.55]{.././Figures/split/4-3.pdf}](img285.svg)

![\includegraphics[scale=0.55]{.././Figures/split/4-4.pdf}](img287.svg)

![$\displaystyle \underset{=}{\sigma} =

\left[

\begin{array}{ccc}

\sigma_{NN} ...

...ccc}

8580 & 100 & 0 \\

100 & 9900 & 0 \\

0 & 0 & 9000

\end{array} \right]$](img288.svg) psi

psi

![\begin{displaymath}\begin{array}{rcl}

\sum F_1 & = & 0 \\

\sum F_1 & =

& + S_{1...

...] dx_1 dx_2 \\

& & - \rho (dx_1 dx_2 dx_3) b_1 = 0

\end{array}\end{displaymath}](img311.svg)

![\includegraphics[scale=0.65]{.././Figures/split/4-5.pdf}](img314.svg)

![\includegraphics[scale=0.45]{.././Figures/split/4-7.pdf}](img319.svg)

![\includegraphics[scale=0.55]{.././Figures/split/4-8.pdf}](img324.svg)

![\includegraphics[scale=0.55]{.././Figures/split/4-DispStrains.PNG}](img325.svg)

) in direction 1 only. This type of deformation produces a change of volume of the solid and therefore contributes to volumetric strain. The resulting deformation or strain (change of length divided original length) is

) in direction 1 only. This type of deformation produces a change of volume of the solid and therefore contributes to volumetric strain. The resulting deformation or strain (change of length divided original length) is

![$\pi - \left[ \pi - \arctan(\Delta u_1 / \Delta x_2) + \arctan(\Delta u_2 / \Delta x_1) \right] $](img328.svg) . The shear strain is 1/2 of the total change of the angle and therefore (for small changes

. The shear strain is 1/2 of the total change of the angle and therefore (for small changes

)

)

![$\displaystyle \varepsilon_{vol} = \frac{[(\mathrm{d} x_1 + \mathrm{d}u_1)(\math...

...athrm{d} x_2 \mathrm{d} x_3)]}{(\mathrm{d} x_1 \mathrm{d} x_2 \mathrm{d} x_3)}

$](img341.svg)

[N] required to produce an elongation

[N] required to produce an elongation  [m] in a spring with mechanical constant

[m] in a spring with mechanical constant  [N/m] is

[N/m] is

and length

and length  . The force required to produce an elongation

. The force required to produce an elongation  [m] is inversely proportional to

[m] is inversely proportional to  , and proportional to proportional to

, and proportional to proportional to  , and

, and  (the stiffness modulus of the solid), such that

(the stiffness modulus of the solid), such that

and strain

and strain

is proportional to the strain tensor

is proportional to the strain tensor

through the stiffness tensor

through the stiffness tensor

(or

(or

) and the strain in the direction of the applied stress

) and the strain in the direction of the applied stress

These two coefficients are the two coefficients conventionally used as elasticity constants in continuum mechanics.

We will see later that in the subsurface we almost never find conditions of laterally “unconfined” stress loading like the one shown in Figure 3.11.

These two coefficients are the two coefficients conventionally used as elasticity constants in continuum mechanics.

We will see later that in the subsurface we almost never find conditions of laterally “unconfined” stress loading like the one shown in Figure 3.11.

![\includegraphics[scale=0.65]{.././Figures/split/4-14.pdf}](img367.svg)

psi

psi MPa

MPa MPa

MPa

GPa

GPa

GPa

GPa

GPa

GPa

![$G=E/[2(1+\nu)]$](img381.svg)

![\begin{displaymath}%compliance matrix

\left[

\begin{array}{c}

\varepsilon_{11} ...

...ma_{13} \cfrac{}{}\\

\sigma_{12} \cfrac{}{}

\end{array}\right]\end{displaymath}](img387.svg)

![$\uuline{\sigma} = [0,0,\sigma_{33},0,0,0]^T$](img388.svg)

![$\displaystyle \uuline{\varepsilon} = \left [ -\cfrac{\nu}{E} \: \sigma_{33},-\cfrac{\nu}{E} \: \sigma_{33},\cfrac{1}{E} \: \sigma_{33},0,0,0 \right]^T $](img390.svg)

and

and  .

.

![$\displaystyle \sigma_{11} = \cfrac{E}{(1+\nu)(1-2\nu)}

\left[ (1-\nu) \varepsilon_{11} + \nu \varepsilon_{22} + \nu \varepsilon_{33} \right]$](img395.svg)

![\begin{displaymath}%compliance matrix

\left[

\begin{array}{c}

\sigma_{11} \\

\...

...3} \\

2 \varepsilon_{12}

\end{array}\right] \: \: \blacksquare\end{displaymath}](img401.svg)

![\includegraphics[scale=0.55]{.././Figures/split/4-21.pdf}](img404.svg)

![$\uuline{\varepsilon} = [0,0,\varepsilon_{33},0,0,0]^T$](img414.svg)

![]() (assuming zero tectonic strains):

(assuming zero tectonic strains):

![]() psi/ft,

psi/ft,

![]() psi/ft, and

psi/ft, and

![]() , the fracture gradient is

, the fracture gradient is

![]() psi/ft. Figure XX shows a schematic example of the calculated fracture gradient.

psi/ft. Figure XX shows a schematic example of the calculated fracture gradient.

![$\uuline{\varepsilon} = [\varepsilon_{11},\varepsilon_{22},\varepsilon_{33},0,0,0]^T$](img430.svg)

.

.

is given.

is given.

and

and

:

:

![]() psi, Poisson's ratio

psi, Poisson's ratio

![$M = (1-\nu) E / [(1+\nu)(1-2\nu)]$](img468.svg)

![$\displaystyle C_{pp} = \frac{1}{M \phi} = \frac{1}{1.6 \times 10^{6} \text{psi}...

...} = 3.1 \: [10^{6} \text{psi}]^{-1} = 3.1 \: \mu \text{sip} \: \: \blacksquare

$](img478.svg)

![$\lambda = (\nu E)/[(1+\nu)(1-2\nu)]$](img481.svg)

![\includegraphics[scale=0.55]{.././Figures/split/LoadingUnloading.pdf}](img492.svg)

![\includegraphics[scale=0.45]{.././Figures/split/4-StressRelaxField.PNG}](img496.svg)

in clockwise direction:

in clockwise direction:

in and the sample length was

in and the sample length was  in. The test was conducted in “as received conditions”. The data is available here.

The data contains Time (s), Axial force

in. The test was conducted in “as received conditions”. The data is available here.

The data contains Time (s), Axial force  (lb), Axial displacement

(lb), Axial displacement  (in), and Radial displacement

(in), and Radial displacement  (in).

(in).

, where

, where  is the cross-sectional area.

is the cross-sectional area.

(

( ) and

) and  (

( ). Notice the radial strain is

). Notice the radial strain is

. Calculate the volumetric strain as well.

. Calculate the volumetric strain as well.

in Voigt notation) show that by applying an isotropic stress

in Voigt notation) show that by applying an isotropic stress

(no shear) the volumetric strain is equal to

(no shear) the volumetric strain is equal to

.

.

, for a shale rock with

, for a shale rock with

psi and

psi and  , when subjected to an isotropic change of stress

, when subjected to an isotropic change of stress

3,000 psi? Write the full (3D) acting stress tensors and resulting strain tensor as matrices 3

3,000 psi? Write the full (3D) acting stress tensors and resulting strain tensor as matrices 3  3.

3.

?

?

in Voigt notation) show that by applying stress in one direction (say 1) and not letting the solid expand in the other two, you can recover the following expression

in Voigt notation) show that by applying stress in one direction (say 1) and not letting the solid expand in the other two, you can recover the following expression

.

.

. Is it lower or higher than E? What is the physical explanation?

. Is it lower or higher than E? What is the physical explanation?

matrices.

matrices.

. Provide answers in

. Provide answers in  sip.

sip.

=0.22 and that horizontal strains are nearly zero.

=0.22 and that horizontal strains are nearly zero.

, tectonic strains are

, tectonic strains are

and

and

, and the shale Young’s modulus is

, and the shale Young’s modulus is