Subsections

Similarly to fluid pressure, rock stresses change with depth.

Yet, changes in rock stresses depend not only on depth but also on the properties of the rock and tectonic stresses if any.

This chapter presents a summary of the calculation of vertical stress (total and effective) and pore pressure with depth.

The chapter also reviews the concept of horizontal stress from a phenomenological point of view.

The calculation of horizontal stress requires a mechanical model that will be introduced in subsequent chapters.

The lithostatic stress gradient is the variation of total vertical stress  with vertical depth (usually referred as true depth in petroleum engineering).

The following subsections review the fundamental concepts of stress, stress equilibrium, and effective stress.

with vertical depth (usually referred as true depth in petroleum engineering).

The following subsections review the fundamental concepts of stress, stress equilibrium, and effective stress.

Consider the solid bar in Figure 2.1.

Two forces

and

and

pull the bar in opposite directions.

Underlining indicates the variable is a vector in

pull the bar in opposite directions.

Underlining indicates the variable is a vector in

(three dimensions).

Equilibrium requires summation of (vectorial) forces to be zero, hence,

(three dimensions).

Equilibrium requires summation of (vectorial) forces to be zero, hence,

.

If the solid bar has a weight, then equilibrium requires

.

If the solid bar has a weight, then equilibrium requires

, the difference is the weight

, the difference is the weight

.

.

Stress is defined as force  over area

over area  (perpendicular to the force) such that

(perpendicular to the force) such that

|

(2.1) |

The units of stress are [Force]/[Area]: MPa, psi, etc., but it does not necessarily mean stress is a pressure!

Stress depends on the direction in which is measured, while pressure is the same in all directions.

The directionality of stress is a result of the solid capacity to resist shear stresses.

Figure 2.1:

1D stress equilibrium.

|

In a 3D porous solid with volume

(Figure 2.2), equilibrium requires the summation of (vectorial) forces in all directions to be zero

(Figure 2.2), equilibrium requires the summation of (vectorial) forces in all directions to be zero

.

Equilibrium of forces in the vertical direction (gravity

.

Equilibrium of forces in the vertical direction (gravity  direction) requires

direction) requires

(forces in vertical direction).

Hence,

(forces in vertical direction).

Hence,

Figure 2.2:

Vertical total stress gradient.

|

Considering infinitesimal variations yields the following equation

|

(2.5) |

The term within the integral in the right-hand-side

is called the vertical total stress gradient, or sometimes, simply as lithostatic stress gradient.

In a semi-infinite medium (e.g. approximation of the Earth's surface)

is called the vertical total stress gradient, or sometimes, simply as lithostatic stress gradient.

In a semi-infinite medium (e.g. approximation of the Earth's surface)

.

.

If

, then vertical stress

, then vertical stress  as a function of depth

as a function of depth  is

is

|

(2.6) |

The total vertical stress is a compressive stress and by convention in geomechanics we assign it a positive sign.

EXAMPLE 2.1:

Assume a rock made of 100% quartz (mass density

) with 20% porosity filled with water (mass density

) with 20% porosity filled with water (mass density  ).

What is the lithostatic stress gradient?

).

What is the lithostatic stress gradient?

SOLUTION

The bulk (volume average) rock mass density

depends on porosity

depends on porosity  , volume fractions of mineral phases, and volume fractions of fluid phases.

For a water-saturated rock:

, volume fractions of mineral phases, and volume fractions of fluid phases.

For a water-saturated rock:

Let's assume typical values

kg/m

kg/m and

and

kg/m

kg/m (check out https://nature.berkeley.edu/classes/eps2/wisc/glossary2.html, look for specific gravity SG).

Then,

This bulk mass density is also equal to 144.8 lb/ft

(check out https://nature.berkeley.edu/classes/eps2/wisc/glossary2.html, look for specific gravity SG).

Then,

This bulk mass density is also equal to 144.8 lb/ft and 19.4 ppg (pounds per gallon), where 1 kg = 2.2 lb, 1 ft = 0.305 m, and 1 ft

and 19.4 ppg (pounds per gallon), where 1 kg = 2.2 lb, 1 ft = 0.305 m, and 1 ft = 7.48 US gallon.

The stress gradient results

Note that 1 N = 1 kg m/s

= 7.48 US gallon.

The stress gradient results

Note that 1 N = 1 kg m/s , 1 Pa = 1 N/m

, 1 Pa = 1 N/m , 1 MPa = 10

, 1 MPa = 10 Pa and 1 Km = 10

Pa and 1 Km = 10 m.

m.

Let us calculate the stress gradient in petroleum field units (psi/ft).

First, we need to convert kg to lb (1 kg = 2.205 lb) and m to ft (1 m = 3.281 ft), thus

kg/m

kg/m lb/ft

lb/ft .

Second, we will pass pounds mass (lb) to pounds force (lbf).

This takes into account multiplying for

.

Second, we will pass pounds mass (lb) to pounds force (lbf).

This takes into account multiplying for  , so you should not multiply any numerical value going from lb to lbf.

Third, we will separate the denominator in area times length, and convert ft

, so you should not multiply any numerical value going from lb to lbf.

Third, we will separate the denominator in area times length, and convert ft to in

to in :

:

lbf/ft lbf/ft lbf/ft lbf/ft 1/ft 1/ft lbf/(12 in) lbf/(12 in) 1/ft 1/ft psi/ft psi/ft |

|

Typical vertical stress gradient are around  psi/ft

psi/ft  MPa/km for porosity

MPa/km for porosity

.

Hydrostatic pore pressure gradient is

.

Hydrostatic pore pressure gradient is  psi/ft

psi/ft  MPa/km.

You may use fluid saturations

MPa/km.

You may use fluid saturations

if the rock has two or more fluids in the pore space to accurately calculate the vertical stress gradient.

You may also use the corresponding mineral volume fractions if the rock is comprised of two or more minerals, e.g., a dolomite-rich shale.

if the rock has two or more fluids in the pore space to accurately calculate the vertical stress gradient.

You may also use the corresponding mineral volume fractions if the rock is comprised of two or more minerals, e.g., a dolomite-rich shale.

Now that we have the stress gradient, we can calculate total stress at a given depth.

Let's consider two cases: onshore and offshore.

First, consider an onshore scenario in which the surface coincides with the water table (in most practical applications this is a reasonable assumption).

Assume a constant fluid density  and constant bulk rock mass density

and constant bulk rock mass density

(remember that it includes fluids within pores).

Then, the pore pressure gradient as a function of depth

(remember that it includes fluids within pores).

Then, the pore pressure gradient as a function of depth  will be

will be

|

(2.7) |

as long as there is a connected pore network path from the surface to the depth  , such that the fluid is in hydrostatic equilibrium (it may not happen sometimes).

The total vertical stress gradient as a function of depth

, such that the fluid is in hydrostatic equilibrium (it may not happen sometimes).

The total vertical stress gradient as a function of depth  is calculated with Equation 2.6 because in onshore conditions the assumption of constant bulk mass density with depth is acceptable.

Both (hydrostatic)

is calculated with Equation 2.6 because in onshore conditions the assumption of constant bulk mass density with depth is acceptable.

Both (hydrostatic)  and

and  increase linearly with depth

increase linearly with depth  with constant mass densities (Figure 2.3).

with constant mass densities (Figure 2.3).

Figure 2.3:

Onshore pressure and vertical stress gradient.  : pore pressure,

: pore pressure,  : vertical total stress,

: vertical total stress,  : effective vertical stress.

: effective vertical stress.

|

The difference between total stress and pore pressure is called “effective stress”; hence, the effective vertical stress is

|

(2.8) |

Effective stresses in the subsurface are mostly compressive. Compressive effective stress holds rock together and compacts them.

Notice that  must hold in order to have a compressive effective vertical stress.

We will see later that effective stress is a very important quantity and dictates rock deformation and failure.

Figure 2.4 shows an example of effective stress making cohesionless ground coffee strong and stiff like a brick.

You will see this example in class how I stand on a “brick” of ground coffee thanks to Terzaghi's effective stress and how effective stress strengthens the coffee pack due to friction forces.

must hold in order to have a compressive effective vertical stress.

We will see later that effective stress is a very important quantity and dictates rock deformation and failure.

Figure 2.4 shows an example of effective stress making cohesionless ground coffee strong and stiff like a brick.

You will see this example in class how I stand on a “brick” of ground coffee thanks to Terzaghi's effective stress and how effective stress strengthens the coffee pack due to friction forces.

Figure 2.4:

Example of Terzaghi's effective stress with ground coffee.

|

Similar to the membrane effect conceptualized in Figure 2.4, the mudcake that forms around a wellbore during drilling provides an effective stress to the surrounding rock.

This is a result of the sharp pressure gradient between the mud pressure in the well  and the pore pressure

and the pore pressure  in the formation (Figure 6.4).

in the formation (Figure 6.4).

Figure 2.5:

Schematic of mudcake effect to provide effective stress on the wall of a wellbore.

|

EXAMPLE 2.2:

Compute the pore pressure and vertical stress at 4000 ft of depth (True Vertical Depth: TVD) underneath an onshore drilling rig.

The pore pressure gradient is hydrostatic with brine mass density of 1.04 g/cm and the average rock bulk mass density is about 2.35 g/cm

and the average rock bulk mass density is about 2.35 g/cm .

Make a plot of pressure and vertical stress versus depth.

Show results in MPa and psi.

.

Make a plot of pressure and vertical stress versus depth.

Show results in MPa and psi.

SOLUTION

The corresponding hydrostatic and lithostatic gradients are (keep in mind that 1 g/cm = 1 g/cc = 1000 kg/m

= 1 g/cc = 1000 kg/m ):

):

and

Hence, the pore pressure and hydrostatic gradient at 4000 ft (1219.2 m) of depth are

and

Note: 1 MPa = 145 psi.

In an offshore case we have to take into account the presence of overlying water weight proportional to thickness  .

Again, let us assume constant mass densities for simplicity.

In the water, you cannot define a stress because there is no solid phase.

Within the water zone, fluid pressure will increase according to Eq. 2.7.

This fluid pressure will continue increasing within the seafloor sediments as long as there is a connected pore network from the seafloor to depth

.

Again, let us assume constant mass densities for simplicity.

In the water, you cannot define a stress because there is no solid phase.

Within the water zone, fluid pressure will increase according to Eq. 2.7.

This fluid pressure will continue increasing within the seafloor sediments as long as there is a connected pore network from the seafloor to depth  .

Stresses start to develop at the seafloor beyond depth

.

Stresses start to develop at the seafloor beyond depth  (Figure 2.6), such that the total vertical stress will be

(Figure 2.6), such that the total vertical stress will be

for for |

(2.9) |

Figure 2.6:

Offshore pressure and total stress gradient.

|

Notice that the total stress does not start at 0 at the seafloor  .

However, the important and “physically meaningful” quantity is effective stress and this one does start at zero at the seafloor.

.

However, the important and “physically meaningful” quantity is effective stress and this one does start at zero at the seafloor.

for for |

(2.10) |

This makes sense because otherwise an octopus would not be able to dig in sand at the seafloor (take a look at this video https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LSeYVTo7DFs).

We will see later that stress is a “tensor” (with magnitude that depends on the orientation of the plane in which it is measured) and that pore pressure affects effective stresses in the normal directions.

EXAMPLE 2.3: Compute the pore pressure and vertical stress at 9000 ft of depth (TVD) underneath an offshore drilling rig with water depth of 2000 ft.

The pore pressure gradient is 0.44 psi/ft and the lithostatic gradient is 1 psi/ft.

The hydrostatic pressure gradient above the seafloor is 0.44 psi/ft as well.

Make a plot of pressure and vertical stress versus depth. Calculate effective stress at 9000 ft of depth.

Show results in MPa and psi.

SOLUTION

The pore pressure and hydrostatic gradient at  = 9000 ft of total depth with water depth

= 9000 ft of total depth with water depth  = 2000 ft are

= 2000 ft are

and

hence,

The values in SI units are

MPa,

MPa,

MPa, and

MPa, and

MPa.

MPa.

For an interactive example of calculation of vertical stress with depth, check my Jupyter notebook at https://mybinder.org/v2/gh/dnicolasespinoza/GeomechanicsJupyter/master?filepath=PorePressureVerticalStress_Widget.ipynb

In the general case rock bulk mass density

varies with depth. For example, rock lithology will vary with depth.

Rocks usually have lower porosity as depth increases.

Brine mass density also changes with depth.

In general, vertical stress is calculated from integration of the equation

varies with depth. For example, rock lithology will vary with depth.

Rocks usually have lower porosity as depth increases.

Brine mass density also changes with depth.

In general, vertical stress is calculated from integration of the equation

|

(2.11) |

where

is obtained from (gamma ray) density well logs and

is obtained from (gamma ray) density well logs and  is obtained from the true vertical depth (TVD) calculated from the well measured depth (MD) and the well deviation survey (Figure 2.7).

Accurate calculations should account for the difference between the rotary table or kelly bushing (from where measured depth is often obtained) and the actual ground level.

This difference can be significant in offshore cases.

In deviated wellbores, you should also take into account wellbore deviation and compute TVD from MD and well trajectory.

is obtained from the true vertical depth (TVD) calculated from the well measured depth (MD) and the well deviation survey (Figure 2.7).

Accurate calculations should account for the difference between the rotary table or kelly bushing (from where measured depth is often obtained) and the actual ground level.

This difference can be significant in offshore cases.

In deviated wellbores, you should also take into account wellbore deviation and compute TVD from MD and well trajectory.

Figure 2.7:

Variables involved in the calculation of vertical stress in the general case.

|

Well logs contain “discrete” data, hence you have to do numerical integration.

Equation 2.11 can be approximated with

|

(2.12) |

where  is the i-th interval at depth

is the i-th interval at depth  .

You can code this equation as the “trapezoidal rule" in a for loop or in a spreadsheet.

For example, the vertical stress at the

.

You can code this equation as the “trapezoidal rule" in a for loop or in a spreadsheet.

For example, the vertical stress at the  -th layer is

-th layer is

![$\displaystyle S_v(i) = \left[ \frac{ \rho_{bulk}(i) + \rho_{bulk}(i-1)}{2} \right] g \left[ z(i) - z(i-1) \right] + S_v(i-1)$](img186.svg) |

(2.13) |

where

![$\left[ ( \rho_{bulk}(i) + \rho_{bulk}(i-1))/2 \right] g $](img187.svg) is the average height of the trapezoid,

is the average height of the trapezoid,

![$\left[ z(i) - z(i-1) \right]$](img188.svg) is the base of the trapezoid, and

is the base of the trapezoid, and  is the total stress at the previous depth data point calculated with the same rule, but one level above.

The result is the addition of the weight of all layers above the point under consideration.

is the total stress at the previous depth data point calculated with the same rule, but one level above.

The result is the addition of the weight of all layers above the point under consideration.

EXAMPLE 2.4: Go to https://github.com/dnicolasespinoza/GeomechanicsJupyter and download the files 1_14-1_Composite.las and 1_14-1_deviation_mod.dev.

The first one is a well logging file (.LAS).

You will find here measured depth (DEPTH - Track 1) and bulk mass density (RHOB - Track 8).

Track 3 also shows bulk density correction (DRHO).

Add RHOB to DRHO to obtain the corrected bulk mass density.

The second file has the deviation survey of the well.

Use this file to calculate true vertical depth subsea (TVDSS) as a function of measured depth (MD) in the well logging file.

You may assume an average bulk mass density of 2 g/cc between the seafloor and the beginning of the density data.

Apply Equation 2.12.

Summations with discrete data sets can be easily done through a for loop.

SOLUTION

See Figure 2.8.

You may use the library https://pypi.org/project/lasio/ to open LAS files with python or write your own code to read the text files .LAS and .DEV.

Figure 2.8:

Example of calculation of vertical stress for a general case. This is an offshore example in the North Sea with seafloor at 104 m of depth. The calculation assumes an average bulk mass density of 2 g/cc between the seafloor and 1000 m TVDSS (True Vertical Depth SubSea).

|

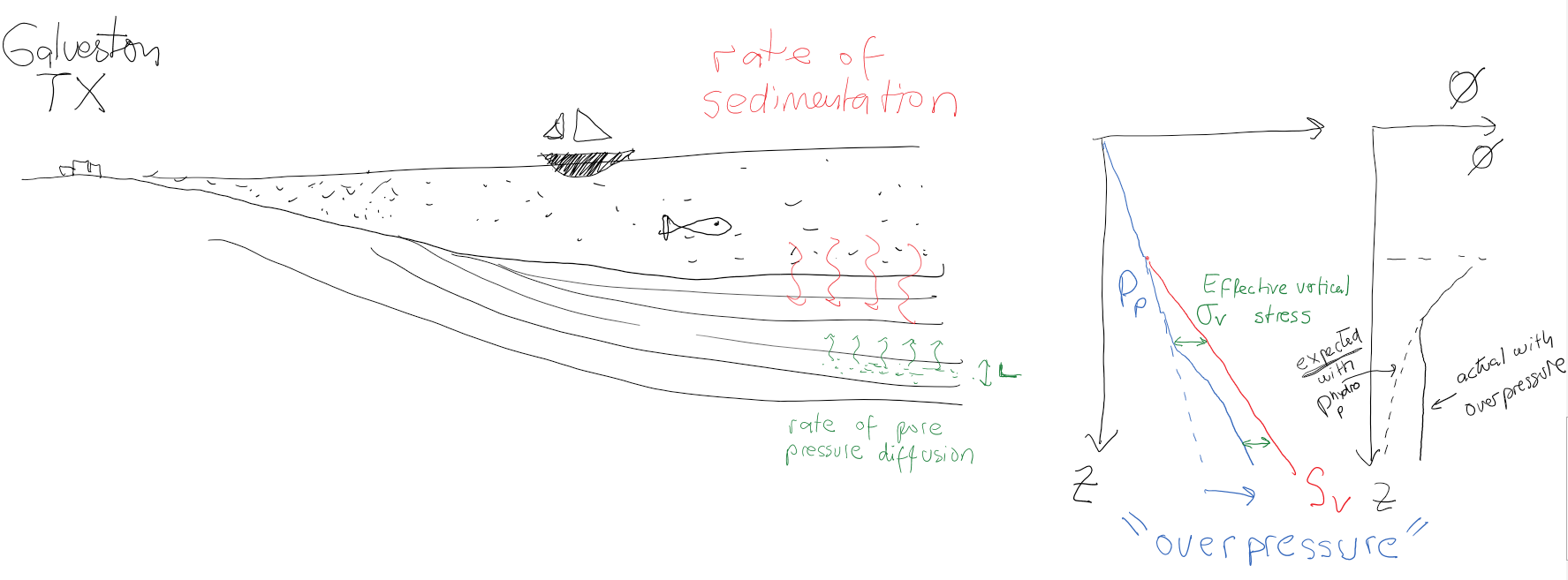

2.2 Non-hydrostatic pore pressure

Pore pressure is not hydrostatic everywhere.

In fact, many times pore pressure is an unknown!

In a system of “connected pores” under hydrostatic equilibrium (water does not move), pore pressure increases hydrostatically.

Non-hydrostatic variations of pore pressure are usually located adjacent to low permeability barriers (e.g., shale formations) that do not allow pore pressure to achieve hydrostatic equilibrium fast enough compared to the rate of sedimentation and pore pressure relief.

Hence, pore pressure gets locked-in.

In the example in Figure 2.9, pore pressure is hydrostatic until

ft.

Overpressure develops from

ft.

Overpressure develops from

ft to

ft to

ft (likely due to a low permeability mudrock).

Pore pressure below

ft (likely due to a low permeability mudrock).

Pore pressure below

ft is quite different from hydrostatic!

ft is quite different from hydrostatic!

Figure 2.9:

Overpressure example in the Monte Cristo field (Image credit: [Zoback 2013]).

|

A convenient parameter to relate pore pressure and total vertical stress is the dimensionless overpressure parameter  :

:

|

(2.14) |

In stationary conditions  cannot be larger than

cannot be larger than  , hence,

, hence,

.

In onshore conditions

.

In onshore conditions

means hydrostatic pore pressure (

means hydrostatic pore pressure (

in hydrostatic conditions offshore, why?).

Reservoir overpressure is good for hydrocarbon recovery (more energy to flow to the wellbore), however, it may cause geomechanical challenges for drilling (kicks).

Parameter

in hydrostatic conditions offshore, why?).

Reservoir overpressure is good for hydrocarbon recovery (more energy to flow to the wellbore), however, it may cause geomechanical challenges for drilling (kicks).

Parameter

means little effective stress.

We will see later that rocks have effective stress-dependent strength.

Hence, overpressure leads to weak rocks, especially if they are not well cemented, difficult to drill.

means little effective stress.

We will see later that rocks have effective stress-dependent strength.

Hence, overpressure leads to weak rocks, especially if they are not well cemented, difficult to drill.

There are several mechanisms that may contribute to overpressure

.

First, hydrocarbon accumulations create overpressure due to buoyancy.

Overpressure

.

First, hydrocarbon accumulations create overpressure due to buoyancy.

Overpressure

is proportional to hydrocarbon column height

is proportional to hydrocarbon column height  and difference in mass density of pore fluids

and difference in mass density of pore fluids

|

(2.15) |

where  is measured from the hydrocarbon-brine contact line upwards.

A connected pore structure is needed throughout the buoyant phase.

is measured from the hydrocarbon-brine contact line upwards.

A connected pore structure is needed throughout the buoyant phase.

Figure 2.10:

Mechanisms of overpressure: Hydrocarbon column.

|

Second, changes in temperature cause fluids to dilate. If the fluids cannot escape quickly enough, then pore pressure increases.

Third, clay diagenesis can expell water molecules. For example, when montmorillonite converts to illite at high pressure and temperature, previously bound water molecules get “added” to the pore space. Under constant pore volume conditions, such addition will result in increases of pore pressure.

Fourth, hydrocarbon generation also induces overpressure. With hydrocarbon generation, the original organic compounds transform in another phase which occupies more volume at the same pressure conditions. Overpressure in organic-rich shales is a good indicator of hydrocarbon presence.

Figure 2.11:

Other mechanisms of overpressure

|

Changes of vertical and horizontal stresses can induce pore pressure changes.

Pore pressure increases when a rock/sediment is compressed (such that the pore volume decreases) under conditions in which the fluid cannot escape quickly enough.

Figure 2.12 shows a schematic representation of this concept.

- (LEFT) A weight is added on a receptacle with a moving top lid. The top has a hole so that water can escape through the tube when the valve is not closed. The valve is closed now, so the water takes the weight

and pore pressure increases a magnitude

and pore pressure increases a magnitude

, where

, where  is the area of the top lid.

is the area of the top lid.

- (MIDDLE) Somebody opens the valve. The fluid starts to drain out. When the top touches the sediment grains, the weight

starts to transfer to the sediment, so that the water takes now just a fraction of the weight and pore pressure reduces accordingly.

starts to transfer to the sediment, so that the water takes now just a fraction of the weight and pore pressure reduces accordingly.

- (RIGHT) The sediment takes all the load

so now the vertical effective stress on the top is

so now the vertical effective stress on the top is

. The fluid does not support the weight

. The fluid does not support the weight  anymore

anymore

. The time it takes to arrive to this scenario depends on the tube and valve hydraulic conductivity and the overpressure generated by the weight

. The time it takes to arrive to this scenario depends on the tube and valve hydraulic conductivity and the overpressure generated by the weight  .

.

Figure 2.12:

Schematic of the consolidation problem.

|

Imagine now a sediment layer saturated with water.

There is an impervious layer at the bottom.

Water cannot escape from the sides either.

Water can only escape from the top.

Figure 2.13:

Disequilibrium compaction: initial conditions

|

An overburden is placed quickly on the sediment so that it compacts an amount  .

Initially, the pore pressure increases everywhere the same amount.

The pore pressure decreases preferentially at the top boundary (where it can flow) and the rate of pore pressure change is proportional to the hydraulic diffusivity parameter

.

Initially, the pore pressure increases everywhere the same amount.

The pore pressure decreases preferentially at the top boundary (where it can flow) and the rate of pore pressure change is proportional to the hydraulic diffusivity parameter

|

(2.16) |

where  is the constrained rock “stiffness” (inverse of 1D compressibility

is the constrained rock “stiffness” (inverse of 1D compressibility  ),

),  is the sediment (vertical) permeability, and

is the sediment (vertical) permeability, and  is the fluid viscosity.

The one-dimensional equation to this problem is

is the fluid viscosity.

The one-dimensional equation to this problem is

|

(2.17) |

Figure 2.14:

Disequilibrium compaction: load application

|

The solution of the partial differential equation above give us a characteristic time  for which

for which  of the pore pressure is relieved,

of the pore pressure is relieved,

|

(2.18) |

where  is the characteristic distance of drainage.

In our example

is the characteristic distance of drainage.

In our example  is the thickness of the sediment layer, the longest straight path to a draining boundary.

is the thickness of the sediment layer, the longest straight path to a draining boundary.

EXAMPLE 2.5: Calculate the characteristic time of pore pressure diffusion for a 100 m thick sediment with top drainage considering

(a) a sand with  100 mD and

100 mD and  1 GPa, and

1 GPa, and

(b) a mudrock with  100 nD and

100 nD and  1 GPa.

1 GPa.

The water viscosity is 1 mPa s.

SOLUTION

(a) Sand:

1.1 day.

1.1 day.

(b) Mudrock:

3000 years.

3000 years.

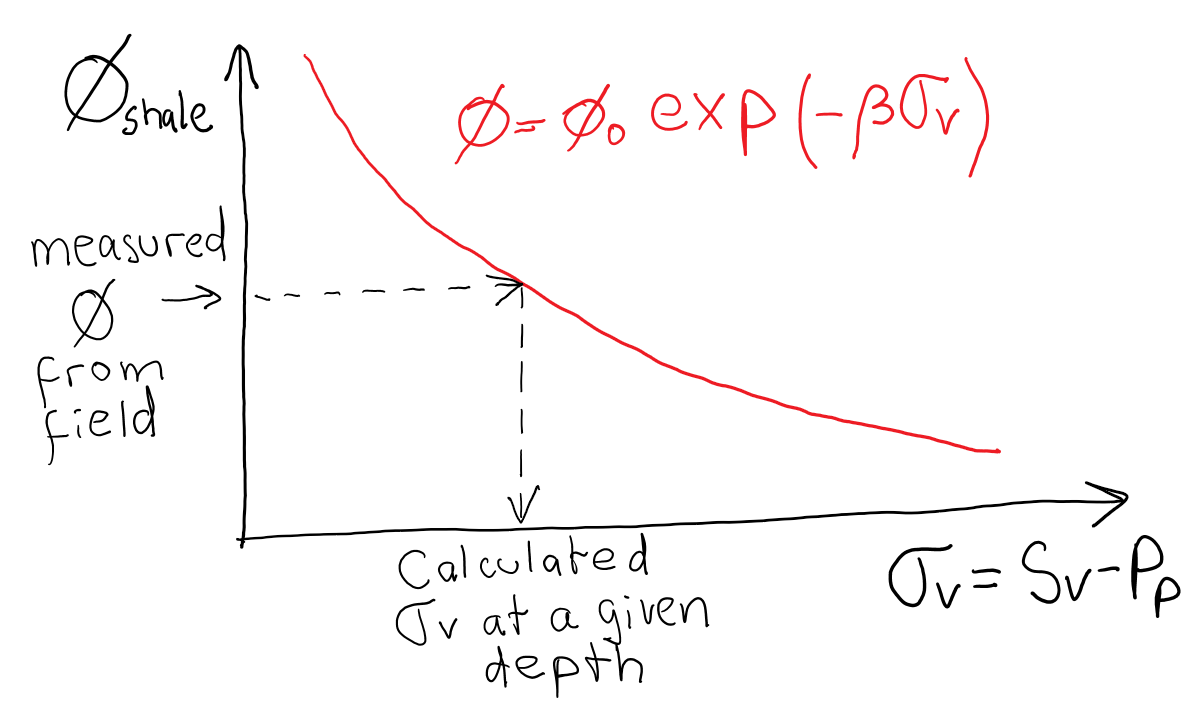

The example in Figure 2.16 is a measurement of pore pressure  that utilizes measurements of porosity in mudrocks (Track 3) to predict overpressure (Track 4).

The concept is simple: the porosity of clay-rich rock decreases with effective stress (Figure 2.15).

Let us assume the following equation for such dependence

that utilizes measurements of porosity in mudrocks (Track 3) to predict overpressure (Track 4).

The concept is simple: the porosity of clay-rich rock decreases with effective stress (Figure 2.15).

Let us assume the following equation for such dependence

|

(2.19) |

Figure 2.15:

Schematic example of shale porosity as a function of effective vertical stress. Effective stress (rather than total stress) causes rock mechanical compaction.

|

Under hydrostatic pore pressure conditions, vertical effective stress will always increase with depth.

However, in the presence of overpressure, effective stress may increase less steeply or even decrease with depth. Hence, mudrocks with porosity higher than the porosity expected at that depth (in hydrostatic conditions) indicate overpressured sediment intervals (Figure 2.17).

Figure 2.16:

Example of overpressure in the Gulf of Mexico.

|

Figure 2.17:

Schematic representation of overpressure due to disequilibrium compaction. Overpressure develops when the rate of sedimentation exceeds the rate of pore pressure diffusion, i.e., water does not have enough time to escape when squeezed within the rock.

|

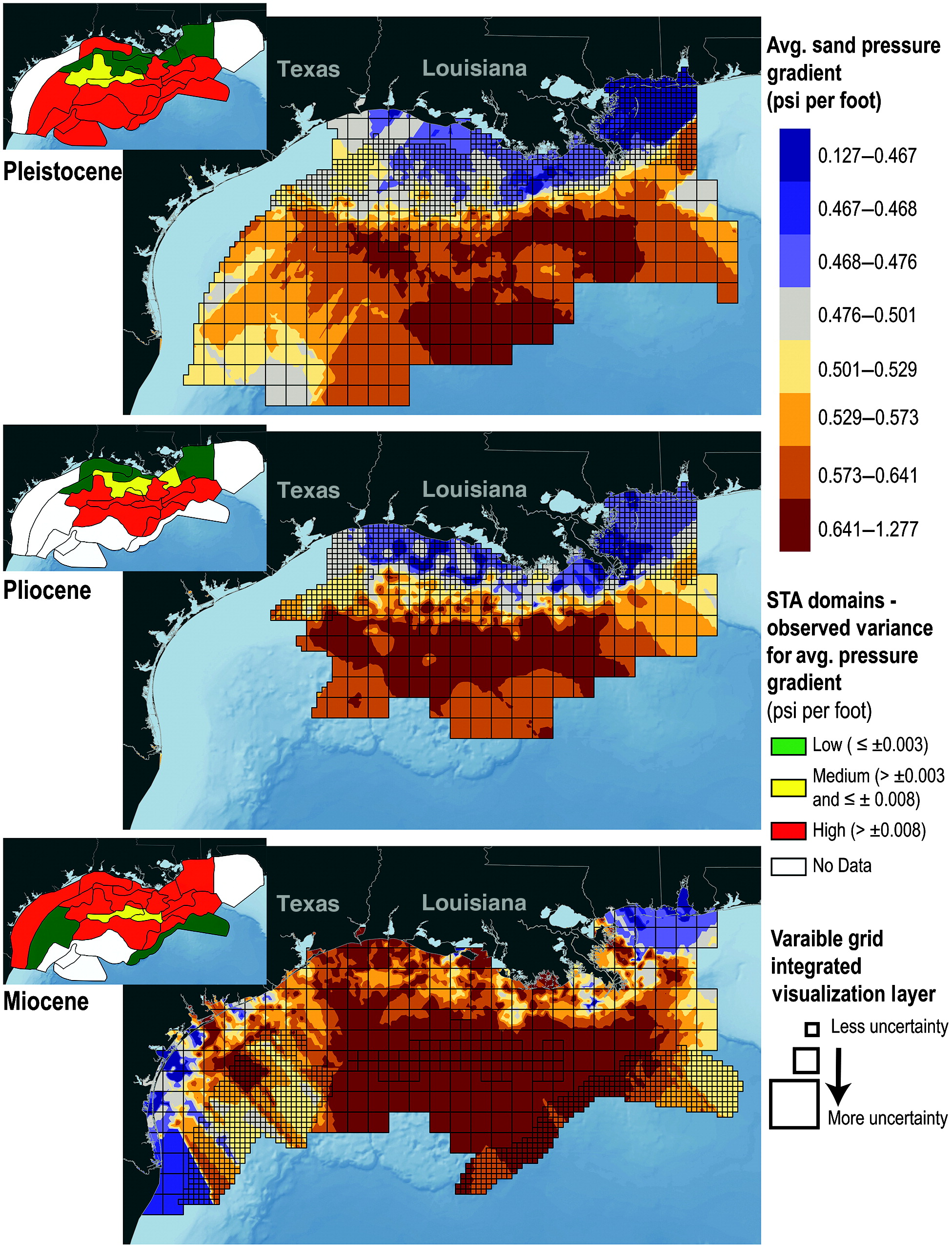

Figure 2.18 shows maps of pressure gradients in the Gulf of Mexico.

Data from offshore locations show that overpressure (gradient  0.44 psi/ft ) starts to develop at 2 to 3 km of depth below seafloor.

0.44 psi/ft ) starts to develop at 2 to 3 km of depth below seafloor.

Figure 2.18:

Pore pressure gradients in the Gulf of Mexico (GOM). Overpressure (gradient  0.44 psi/ft) in GOM is mostly due to disequilibrium compaction and often increases with depth (depth increasing from Pleistocene to Miocene). Source: Rose et al. 2020, https://doi.org/10.1190/INT-2019-0019.1.

0.44 psi/ft) in GOM is mostly due to disequilibrium compaction and often increases with depth (depth increasing from Pleistocene to Miocene). Source: Rose et al. 2020, https://doi.org/10.1190/INT-2019-0019.1.

|

EXAMPLE 2.6: Calculate the pore pressure  and overpressure parameter

and overpressure parameter  in a muddy sediment located offshore with porosity

in a muddy sediment located offshore with porosity

.

The total depth is 2000 m and the water depth is 500 m (assume a lithostatic gradient of 22 MPa/km below the seafloor).

Laboratory tests indicate a compaction curve with parameters

.

The total depth is 2000 m and the water depth is 500 m (assume a lithostatic gradient of 22 MPa/km below the seafloor).

Laboratory tests indicate a compaction curve with parameters

MPa

MPa and

and

.

How much higher than expected hydrostatic value is the pore pressure?

.

How much higher than expected hydrostatic value is the pore pressure?

SOLUTION

First, calculate total vertical stress:

Second, calculate effective vertical stress from using the measured porosity and Equation 2.19:

MPa MPa |

|

Third, calculate pore pressure from

, so

, so

Hence, the overpressure parameter is

2.2.3 Reservoir depletion

Opposite to overpressure, “underpressure” occurs when pore pressure is lower than hydrostatic.

The most common reason of underpressure is reservoir depletion.

In compartmentalized reservoirs with poor water recharge drive, pore pressure may stay low for long periods of time.

Reservoir depletion usually brings along lower total horizontal stresses which lower the fracture gradient and make drilling problematic because of decreased difficulty to create open-mode fractures.

Figure 2.19:

Example of decreased fracture pressure (between 5,100 ft and 5,400 ft) due to depletion of sandy intervals.

|

Vertical (effective) stress is not enough to define the state of stress in a solid.

Stresses in horizontal direction are very often different to the stress in vertical direction.

The state of stress can be fully defined by the “principal stresses”.

These are three independent normal stresses in directions all perpendicular to each other.

A stress is a principal stress if there is no shear stress on the plane in which it is applied.

Total vertical stress  may not be a principal stress, although in most cases it is.

If vertical stress is a principal stress, then the two other principal stresses are horizontal.

The maximum principal stress in the horizontal case is

may not be a principal stress, although in most cases it is.

If vertical stress is a principal stress, then the two other principal stresses are horizontal.

The maximum principal stress in the horizontal case is  and the minimum horizontal stress is

and the minimum horizontal stress is  , such that

, such that

(Figure 2.20).

(Figure 2.20).

Figure 2.20:

The stress tensor when vertical stress is a principal stress.

|

We have seen that total vertical stress is mostly a function of overburden and depth.

Now, what determines horizontal stresses?

There is not an easy answer for that.

Many variables affect and limit horizontal stresses.

First, there are “background” horizontal stresses that develop due to the weight of overburden, its compaction, and “pushing sideways” effect.

For example, water pushes sideways with all its weight (pressure is the same in all directions).

Solids push sideways with a fraction of their weight.

Second, horizontal stresses may deviate from background stresses - to be either more or less compressive.

Tectonic plate movements are the main contributors to variations of horizontal stress.

Convergent plates increase horizontal compression.

Divergent plates decrease horizontal compression.

Shear stresses develop at transform boundaries.

Other factors include topography, crustal thickening/thinning, mass density anomalies, buoyancy forces, and lithospheric flexure (similar effect of a loaded slab).

Figure 2.21:

Example of a transform plate boundary

|

The direction of maximum horizontal stress varies with location around the Earth's crust.

Tectonic plate movements are the main contributors the affect the direction of maximum horizontal stress (See Figure 2.22).

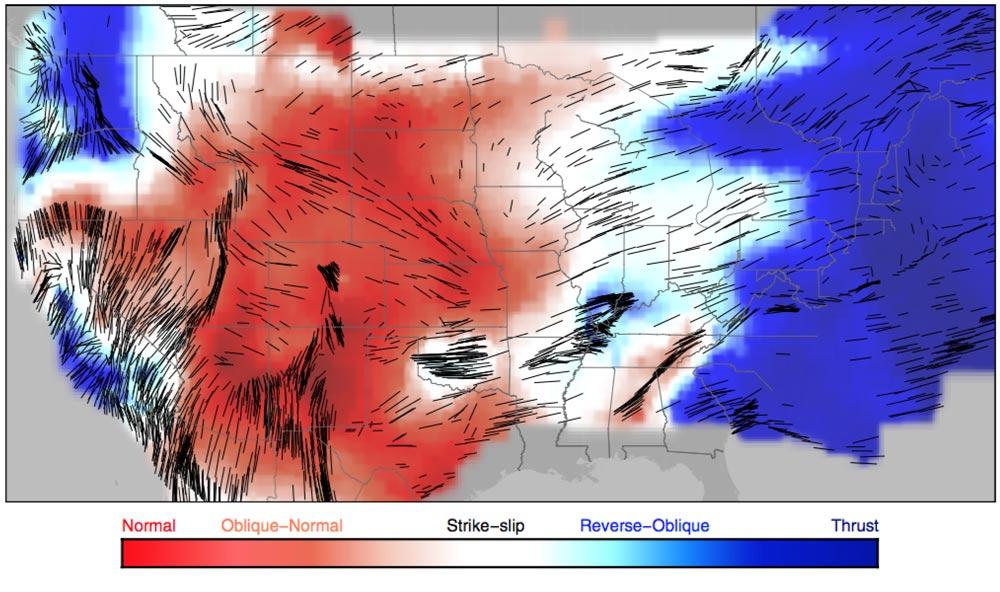

Figure 2.22:

Horizontal stress map. The direction of maximum horizontal stress is affected by tectonic plate movement. The maximum principal stress is horizontal in compressional and strike-slip stress faulting regimes. The minimum principal stress is horizontal in extensional domains.

|

Geological formations can be indicators of “paleo-stress” direction, that is, the stress that caused such feature at a particular time.

The paleo-stress, however, may be different from the current state of stress in magnitude and direction.

Keep in mind that the Earth crust today is the results of millions of years of plate movement, smashing, and thinning/thickening (see this great animation of the Earth crust evolution since the Precambrian https://dinosaurpictures.org/ancient-earth#150.)

The orientation of fault planes is an indicator of the state of stress that caused such fault. This topic will be seen later in “Fault stability" analysis.

Folding direction also can give an idea of the horizontal stress that produced such fold.

Natural fractures can be indicators of shear or open mode fractures.

Both are related to the orientation of the state of stress.

Earthquake focal mechanisms tell about the polarity of waves emitted by rock failure, where rock failure is also related to the orientation of the state of stress (to be covered later).

Magmatic and sedimentary dikes are natural hydraulic fractures. They form when a pressurized fluid/sediment mixture opens the subsurface and props the recently opened space with crystallized magma or sediments.

Dikes, like any other hydraulic fracture, open up preferentially against the least principal stress  .

.

Figure 2.23:

Example of magmatic dike/dyke: large-scale hydraulic fractures.

|

The only way to know the current magnitude (and direction) of the minimum horizontal stress  (if

(if

) is to measure it.

Subsurface measurements of

) is to measure it.

Subsurface measurements of  are based in hydraulic fracturing methods (to be seen in detail later in the course, Chapter 7).

Three types of hydraulic fracture tests are:

are based in hydraulic fracturing methods (to be seen in detail later in the course, Chapter 7).

Three types of hydraulic fracture tests are:

- Extended leak-off test: performed during drilling with drilling mud. The minimum principal stress

is measured at about the value of the fracture closure pressure

is measured at about the value of the fracture closure pressure  .

.

- Mini-frac test: Performed for completion purposes before the main hydraulic fracture treatment with fracturing fluid. The analysis to obtain

is based on the same principles of the extended leak-off test.

is based on the same principles of the extended leak-off test.

- Step-rate test: Used for continuous fluid injection. The formation parting pressure (when a hydraulic fracture forms) is related but higher than

.

.

The variations of horizontal stress in the lithosphere give rise to three types of stress regimes, depending on the relative magnitude of horizontal stress with respect to vertical stress (Table 2.1).

Stress is a tensor.

Every stress tensor has three characteristic values called principal stresses  ,

,  , and

, and  (eigenvalues https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Eigenvalues_and_eigenvectors ).

The principal stress

(eigenvalues https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Eigenvalues_and_eigenvectors ).

The principal stress  is the maximum normal stress value in a given direction (maximum total principal stress).

The principal stress

is the maximum normal stress value in a given direction (maximum total principal stress).

The principal stress  is the minimum normal stress value in a given direction (minimum total principal stress).

The principal stress

is the minimum normal stress value in a given direction (minimum total principal stress).

The principal stress  is an intermediate stress value at a direction perpendicular to

is an intermediate stress value at a direction perpendicular to  and

and  .

Figure 2.24 shows a map of the United States (lower 48 states) with the three types of stress regimes explained in Table 2.1.

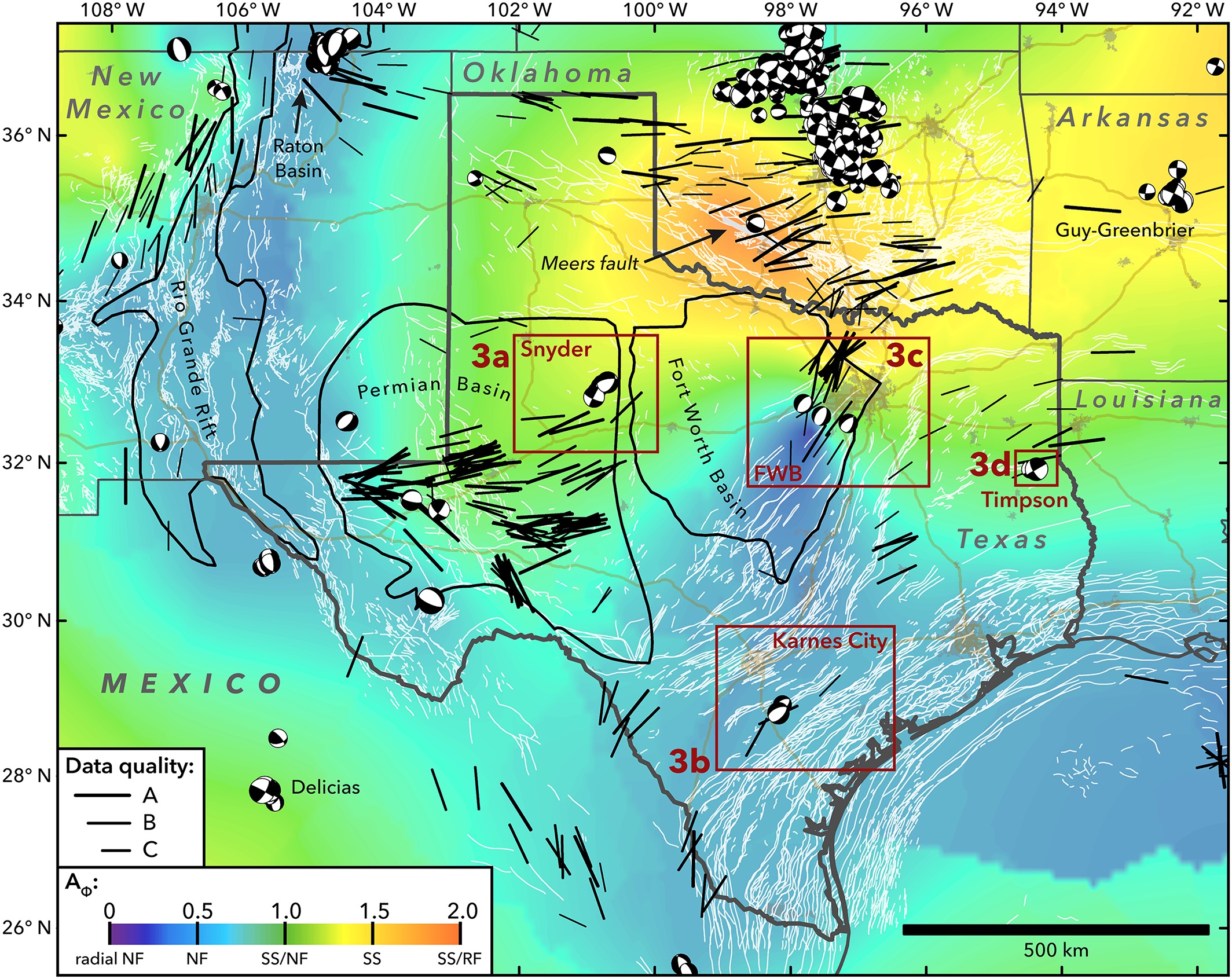

Figure 2.25 shows the variation of stress regimes and horizontal stress diection in Texas.

.

Figure 2.24 shows a map of the United States (lower 48 states) with the three types of stress regimes explained in Table 2.1.

Figure 2.25 shows the variation of stress regimes and horizontal stress diection in Texas.

Table 2.1:

Stress regimes in the subsurface according to the Andersonian classification.

| Stress Regime |

|

|

|

| Normal Faulting |

|

|

|

| Strike-Slip Faulting |

|

|

|

| Reverse/Thrust Faulting |

|

|

|

Figure 2.25:

Stress regimes and horizontal stress direction in Texas, Oklahoma, and New Mexico. The black lines represent the direction of maximum horizontal stress ( ). Source: Snee and Zoback, 2016 https://doi.org/10.1002/2016GL070974.

). Source: Snee and Zoback, 2016 https://doi.org/10.1002/2016GL070974.

|

Normal faulting occurs in tectonically passive or extensional environments, such that

, where

, where  ,

,

,

,

.

The minimum horizontal stress

.

The minimum horizontal stress  can be as low as

can be as low as  % of

% of  , but not much lower.

If lower, sedimentary strata fail creating normal faults due to large differences between effective stresses

, but not much lower.

If lower, sedimentary strata fail creating normal faults due to large differences between effective stresses

and

and

.

Hydraulic fractures in this environment would be vertical (perpendicular to

.

Hydraulic fractures in this environment would be vertical (perpendicular to  direction).

Most hydrocarbon-producing basins in the USA are in normal faulting stress regimes.

direction).

Most hydrocarbon-producing basins in the USA are in normal faulting stress regimes.

Strike slip faulting occurs in “mild” tectonically compressive environments, such that

where

where

,

,  , and

, and

.

These stress regimes cause strike-slip faults when

.

These stress regimes cause strike-slip faults when  surpasses

surpasses  above the frictional limit.

Hydraulic fractures in this environment are vertical and perpendicular to

above the frictional limit.

Hydraulic fractures in this environment are vertical and perpendicular to  direction.

Some giant oil fields in the middle East are in strike-slip stress regime.

direction.

Some giant oil fields in the middle East are in strike-slip stress regime.

Reverse faulting occurs in “strong” tectonically compressive environments, such that

, where

, where

,

,

,

,  .

These stress regimes cause reverse and thrust faults when

.

These stress regimes cause reverse and thrust faults when  surpasses

surpasses  above the failure limit.

Hydraulic fractures in this environment are horizontal! (perpendicular to

above the failure limit.

Hydraulic fractures in this environment are horizontal! (perpendicular to  direction).

Some unconventional fields in Argentina and Australia are in reverse faulting stress-regime at specific depths.

direction).

Some unconventional fields in Argentina and Australia are in reverse faulting stress-regime at specific depths.

Why is the shape of an inflated balloon spherical (Figure 2.27)?

Even if you were to inflate the ballon under water, it would be still spherical.

The reason is that pressure around the balloon is the same in all directions.

It would be the atmospheric pressure in air at surface conditions or the water pressure

at seafloor conditions.

Now, what would be the shape of a balloon inflated under several layers of sediments?

Would it be spherical or not?

at seafloor conditions.

Now, what would be the shape of a balloon inflated under several layers of sediments?

Would it be spherical or not?

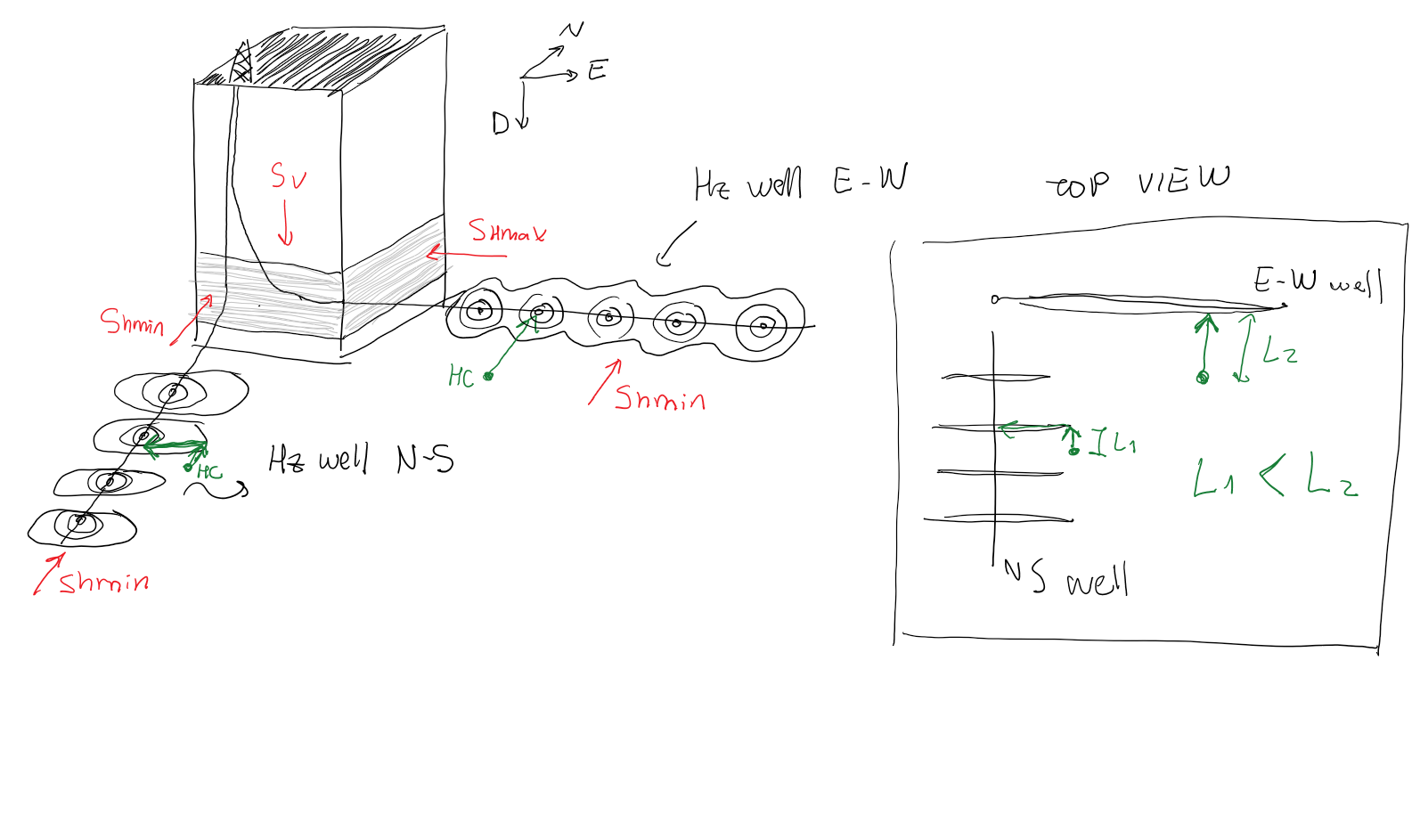

The previous section anticipated the hydraulic fractures are perpendicular to the direction of the least principal stress  .

The reason for such behavior responds to the tendency of nature to go through the path of “least amount of energy”.

There is no reason to push away rock in a direction of higher stress if there is another direction in which stress is lower and it is easier to push.

Thus, hydraulic fractures would be perpendicular to the least principal stress as long as

.

The reason for such behavior responds to the tendency of nature to go through the path of “least amount of energy”.

There is no reason to push away rock in a direction of higher stress if there is another direction in which stress is lower and it is easier to push.

Thus, hydraulic fractures would be perpendicular to the least principal stress as long as  is different and lower than

is different and lower than  and

and  .

As a result, the shape of a balloon inflated under several layers of sediment would be a flat ellipsoid with smallest axis in the direction of

.

As a result, the shape of a balloon inflated under several layers of sediment would be a flat ellipsoid with smallest axis in the direction of  .

.

Figure 2.27:

Ideal orientation of open-mode fractures.

|

Let us consider a place in the subsurface like the one shown in Figure 2.27.

There are three possible cases for the orientation of a hydraulic fracture depending on the values and orientations of the principal stresses.

In Case 1 the least principal stress is horizontal in the direction of axis 2, hence

(the subindices of stresses are explained in detail in the next chapter).

Case 1 is the one drawn on the top right schematic.

In Case 2 the least principal stress is horizontal in the direction of axis 1,

(the subindices of stresses are explained in detail in the next chapter).

Case 1 is the one drawn on the top right schematic.

In Case 2 the least principal stress is horizontal in the direction of axis 1,

.

In Case 3 the least principal stress is vertical in the direction of axis 3,

.

In Case 3 the least principal stress is vertical in the direction of axis 3,

.

.

Given a state of stress, multistage hydraulic fracturing may result or not in independent fracture planes.

Consider the example in Figure 2.28 where

.

The hydraulic fracture planes would always tend to open up against

.

The hydraulic fracture planes would always tend to open up against  regardless of the wellbore orientation.

Multiple hydraulic fractures would tend to link on a single plane if started from a vertical wellbore or a horizontal wellbore drilled in the direction of

regardless of the wellbore orientation.

Multiple hydraulic fractures would tend to link on a single plane if started from a vertical wellbore or a horizontal wellbore drilled in the direction of  .

Hydraulic fractures would have much less tendency to link up if started from a horizontal wellbore drilled in the direction of

.

Hydraulic fractures would have much less tendency to link up if started from a horizontal wellbore drilled in the direction of  .

.

Figure 2.28:

Geometry of open-mode fractures according to wellbore orientation in normal faulting stress environment.

|

For example, the Barnett shale Formation near Dallas-Forth Worth is subjected to a normal faulting stress regime.

Furthermore, the maximum horizontal total stress  is in NE-SW direction (about 60

is in NE-SW direction (about 60 from the North clockwise - Figure 2.29).

As a result, the (least) minimum horizontal stress is oriented 30

from the North clockwise - Figure 2.29).

As a result, the (least) minimum horizontal stress is oriented 30 from the North counter-clockwise.

Consequently, hydraulic fractures are expected to be vertical and the preferential orientation of horizontal wellbores for multistage hydraulic fracturing is either 30

from the North counter-clockwise.

Consequently, hydraulic fractures are expected to be vertical and the preferential orientation of horizontal wellbores for multistage hydraulic fracturing is either 30 from the North counter-clockwise in direction NW or 120

from the North counter-clockwise in direction NW or 120 from the North clockwise in direction SE.

from the North clockwise in direction SE.

Figure 2.29:

Ideal orientation of horizontal wellbores in the Barnett shale.

|

- Compute the vertical stress gradient resulting from a carbonate rock made of 70% dolomite and 30% calcite, porosity 10% and filled with brine 1,060 kg/m

. Look up for mineral densities in the web in trusted sources. Provide answer in psi/ft, MPa/km, and ppg.

. Look up for mineral densities in the web in trusted sources. Provide answer in psi/ft, MPa/km, and ppg.

- Calculate (without the help of a computer) the total vertical stress in an off-shore location at 10,000 ft of total depth (from surface) for which: water depth is 1,000 m (with mass density 1,030 kg/m

), bulk mass density of rock at the seabed is 1,800 kg/m

), bulk mass density of rock at the seabed is 1,800 kg/m increasing linearly until a depth of 500 m below sea-floor to 2,350 kg/m

increasing linearly until a depth of 500 m below sea-floor to 2,350 kg/m and relatively constant below 500 m below seafloor. Why would rock bulk mass density increase with depth?

and relatively constant below 500 m below seafloor. Why would rock bulk mass density increase with depth?

- The following table contains the estimated bulk mass densities for an offshore location in Brazil as a function of true vertical depth sub sea (TVDSS). Water depth is 500 m. Measurements indicate that porosity of shale layers estimated through electrical resistivity measurements.

- Plot the profiles of

v.s. depth (MPa v.s. m and ft v.s psi)

v.s. depth (MPa v.s. m and ft v.s psi)

- Plot the profile of (hypothetical) hydrostatic water pressure. Assume the density of brine is 1,031 kg/m

in the rock pore space (MPa v.s. m and ft v.s. psi).

in the rock pore space (MPa v.s. m and ft v.s. psi).

- Additional compaction lab measurements on shale cores indicate a good fitting of the porosity-effective vertical stress relation through Equation 2.19, with parameters

and

and

MPa

MPa . Estimate the actual pore pressure in the shale. Is there overpressure? At what depth does it start?

. Estimate the actual pore pressure in the shale. Is there overpressure? At what depth does it start?

- According to porosity measurements, does vertical effective stress always increase with depth? Justify.

Note: You are encouraged to summarize all calculations in a single plot as a function of depth (inverted vertical axis): hypothetical pore pressure, actual pore pressure and total vertical stress.

| |

|

|

|

| |

Depth |

Bulk mass density |

Shale porosity |

| |

m m![$]$](img275.svg) |

kg/m kg/m![$^3]$](img276.svg) |

![$[-]$](img277.svg) |

| Water |

0 |

1025 |

NA |

| Water |

100 |

1026 |

NA |

| Water |

200 |

1026 |

NA |

| Water |

300 |

1030 |

NA |

| Water |

400 |

1030 |

NA |

| Water |

500 |

1031 |

NA |

| Sand |

600 |

1900 |

NA |

| Sand |

700 |

2190 |

NA |

| Sand |

800 |

2200 |

NA |

| Sand |

900 |

2230 |

NA |

| Sand |

1000 |

2235 |

NA |

| Sand |

1100 |

2240 |

NA |

| Shale |

1200 |

2275 |

0.305 |

| Shale |

1300 |

2305 |

0.297 |

| Shale |

1400 |

2310 |

0.286 |

| Shale |

1500 |

2308 |

0.281 |

| Shale |

1600 |

2310 |

0.285 |

| Shale |

1700 |

2305 |

0.293 |

| Shale |

1800 |

2310 |

0.307 |

| Shale |

1900 |

2324 |

0.305 |

| Shale |

2000 |

2319 |

0.298 |

- Go to https://github.com/dnicolasespinoza/GeomechanicsJupyter and download the files “HCLonghorn.las” and “HCdeviationsurvey.dev”.

The files include the well logging data and the well trajectory of a well for the Longhorn Field near Plaquemines Parish, Louisiana. The oilfield is an onshore oilfield.

The first one is a well logging file (.las). You will find here measured depth (DEPTH [ft] - Track 1) and bulk mass density (ZDNC [g/cc] - Track 27).

The second file has the deviation survey of the well.

Column 3 is measured depth (MD), column 4 is TVDSS, column 5 is the E-W offset from the surface location, and column 6 is the N-S offset from the surface location.

The water depth at this well location is 38 ft. You may assume an average bulk mass density of 2 g/cc between the surface and the beginning of the bulk density data.

- (optional) Plot the 3-D well trajectory and wellbore direction in a lower hemisphere projection (plot inclination angles and azimuth angles in a polar coordinate system) using the deviation survey.

- Plot TVDSS [ft] as a function of MD [ft]. For this simple trajectory you may use a linear fit to relate TVDSS and MD.

- Plot bulk density (x-axis) verse TVDSS (ft) (y-axis).

- Compute and plot the total vertical stress (psi) (x-axis) versus TVDSS (ft) (y-axis). Compute and plot also the expected hydrostatic pore pressure.

- Based on the US stress map published by the USGS (Fig. 2.24 - https://www.usgs.gov/media/images/new-us-stress-map), answer the following for the Anadarko Basin near mid-center Oklahoma:

- What is the predominant direction of

?.

?.

- What is the predominant stress regime?

- What would the ideal orientation of a hydraulic fracture be in this area?

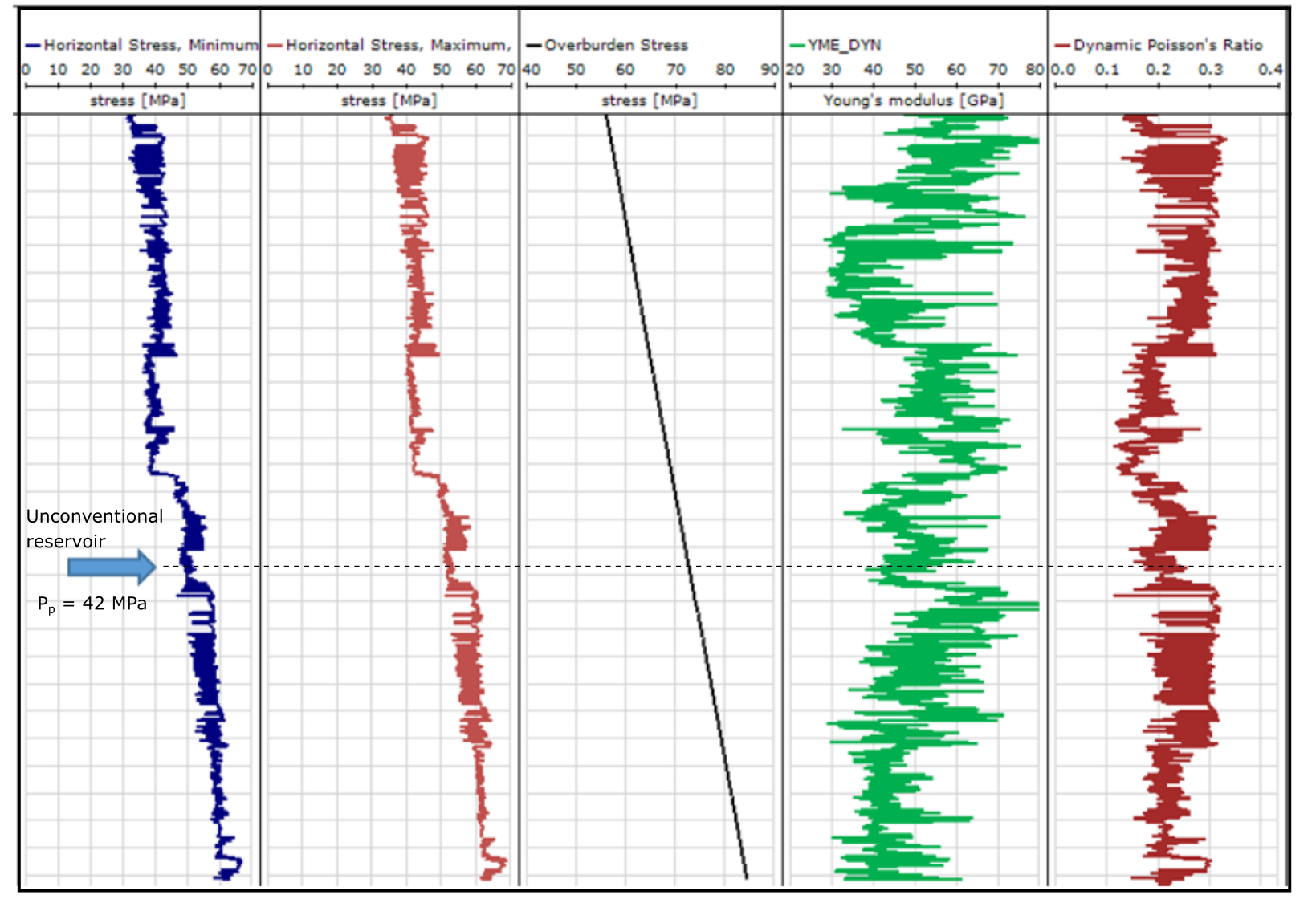

- The following image shows a “stress log” for a location in the Permian Basin (onshore):

- What is the approximate range of depth shown in the stress log?

- What is the approximate depth at the location of the unconventional reservoir (answer specifically at the location of the dashed line - same for following questions)?

- What are the minimum and maximum total horizontal stresses?

- Is the reservoir pressure “hydrostatic”? What is the effective vertical stress?

- What is the stress regime?

Note: You may use a plot digitizer (for example, https://apps.automeris.io/wpd/) to obtain numerical data from image files.

You may use the python code available in the following link at Google Colab: https://drive.google.com/drive/folders/1rIzjFd5p81JGOSRUkaMiQF018idb1XU3?usp=sharing.

I suggest you use it as “inspiration” and learning, but write your own.

Make sure to acknowledge any copying and pasting.

- Fjaer, E., Holt, R.M., Raaen, A.M., Risnes, R. and Horsrud, P., 2008. Petroleum related rock mechanics (Vol. 53). Elsevier. (Chapter 3)

- Zoback, M.D., 2010. Reservoir geomechanics. Cambridge University Press. (Chapter 1 and 2)

kg/m

kg/m and

and

kg/m

kg/m (check out https://nature.berkeley.edu/classes/eps2/wisc/glossary2.html, look for specific gravity SG).

Then,

(check out https://nature.berkeley.edu/classes/eps2/wisc/glossary2.html, look for specific gravity SG).

Then,

kg/m

kg/m kg/m

kg/m kg/m

kg/m

and 19.4 ppg (pounds per gallon), where 1 kg = 2.2 lb, 1 ft = 0.305 m, and 1 ft

and 19.4 ppg (pounds per gallon), where 1 kg = 2.2 lb, 1 ft = 0.305 m, and 1 ft = 7.48 US gallon.

The stress gradient results

= 7.48 US gallon.

The stress gradient results

kg/m

kg/m m/s

m/s Pa/m

Pa/m MPa/km

MPa/km

, 1 Pa = 1 N/m

, 1 Pa = 1 N/m , 1 MPa = 10

, 1 MPa = 10 Pa and 1 Km = 10

Pa and 1 Km = 10 m.

m.

lbf/ft

lbf/ft lbf/ft

lbf/ft 1/ft

1/ft lbf/(12 in)

lbf/(12 in) 1/ft

1/ft psi/ft

psi/ft

![\includegraphics[scale=0.55]{.././Figures/split/2-OnshorePpSv.pdf}](img140.svg)

kg/m

kg/m m/s

m/s MPa/km

MPa/km kg/m

kg/m m/s

m/s MPa/km

MPa/km MPa/km

MPa/km km

km MPa

MPa psi

psi MPa/km

MPa/km km

km MPa

MPa psi

psi

for

for

for

for

psi/ft

psi/ft ft

ft psi/ft

psi/ft ft

ft psi

psi psi/ft

psi/ft ft

ft psi/ft

psi/ft ft

ft psi

psi

psi

psi psi

psi psi

psi

![$\left[ ( \rho_{bulk}(i) + \rho_{bulk}(i-1))/2 \right] g $](img187.svg)

![$\left[ z(i) - z(i-1) \right]$](img188.svg)

![\includegraphics[scale=0.85]{.././Figures/split/2-VertStress_TVDSS.pdf}](img190.svg)

is measured from the hydrocarbon-brine contact line upwards.

A connected pore structure is needed throughout the buoyant phase.

is measured from the hydrocarbon-brine contact line upwards.

A connected pore structure is needed throughout the buoyant phase.

and pore pressure increases a magnitude

and pore pressure increases a magnitude

, where

, where  is the area of the top lid.

is the area of the top lid.

starts to transfer to the sediment, so that the water takes now just a fraction of the weight and pore pressure reduces accordingly.

starts to transfer to the sediment, so that the water takes now just a fraction of the weight and pore pressure reduces accordingly.

so now the vertical effective stress on the top is

so now the vertical effective stress on the top is

. The fluid does not support the weight

. The fluid does not support the weight  anymore

anymore

. The time it takes to arrive to this scenario depends on the tube and valve hydraulic conductivity and the overpressure generated by the weight

. The time it takes to arrive to this scenario depends on the tube and valve hydraulic conductivity and the overpressure generated by the weight  .

.

is the constrained rock “stiffness” (inverse of 1D compressibility

is the constrained rock “stiffness” (inverse of 1D compressibility  ),

),  is the sediment (vertical) permeability, and

is the sediment (vertical) permeability, and  is the fluid viscosity.

The one-dimensional equation to this problem is

is the fluid viscosity.

The one-dimensional equation to this problem is

is the characteristic distance of drainage.

In our example

is the characteristic distance of drainage.

In our example  is the thickness of the sediment layer, the longest straight path to a draining boundary.

is the thickness of the sediment layer, the longest straight path to a draining boundary.

MPa/km

MPa/km km

km MPa/km

MPa/km km

km MPa

MPa

MPa

MPa

MPa

MPa MPa

MPa MPa

MPa

![\includegraphics[scale=0.65]{.././Figures/split/2-17.pdf}](img244.svg)

![\includegraphics[scale=0.55]{.././Figures/split/3-18.pdf}](img248.svg)

is measured at about the value of the fracture closure pressure

is measured at about the value of the fracture closure pressure  .

.

is based on the same principles of the extended leak-off test.

is based on the same principles of the extended leak-off test.

.

.

![\includegraphics[scale=0.55]{.././Figures/split/2-StressProfiles.pdf}](img259.svg)

. Look up for mineral densities in the web in trusted sources. Provide answer in psi/ft, MPa/km, and ppg.

. Look up for mineral densities in the web in trusted sources. Provide answer in psi/ft, MPa/km, and ppg.

), bulk mass density of rock at the seabed is 1,800 kg/m

), bulk mass density of rock at the seabed is 1,800 kg/m increasing linearly until a depth of 500 m below sea-floor to 2,350 kg/m

increasing linearly until a depth of 500 m below sea-floor to 2,350 kg/m and relatively constant below 500 m below seafloor. Why would rock bulk mass density increase with depth?

and relatively constant below 500 m below seafloor. Why would rock bulk mass density increase with depth?

v.s. depth (MPa v.s. m and ft v.s psi)

v.s. depth (MPa v.s. m and ft v.s psi)

in the rock pore space (MPa v.s. m and ft v.s. psi).

in the rock pore space (MPa v.s. m and ft v.s. psi).

and

and

MPa

MPa . Estimate the actual pore pressure in the shale. Is there overpressure? At what depth does it start?

. Estimate the actual pore pressure in the shale. Is there overpressure? At what depth does it start?

m

m![$]$](img275.svg)

kg/m

kg/m![$^3]$](img276.svg)

![$[-]$](img277.svg)

?.

?.