Subsections

4. Rock Yield and Failure

The microstructure of rocks varies widely, from lumped crystals in igneous rocks to fossil carbonate skeletons in diatomite-rich chalk.

We will discuss mostly sedimentary rocks (shown in Fig. 4.1). However, igneous rocks can also host hydrocarbons (really? how?) and constitute the basement of sedimentary basins.

For example, induced seismicity from deep injection of produced-water mostly originates in basement igneous rocks.

Sedimentary rocks include shales, sandstones, and carbonates among other types.

The microstructure of rocks governs their failure properties and characteristics.

For example, uncemented sands cannot hold tensile stresses (Fig. 4.1-a).

At low mean effective stress (as in the sandboarding picture) rock failure happens through grain rotating and roll-over.

Sandstone is formed by cemented grains (Fig. 4.1-b).

At relatively high porosity, the strength of sandstones is dominated by the strength of cemented contacts (bonds).

At failure, the bonds rather than the grains tend to break.

Matrix-supported carbonates form a continuous mineral matrix (Fig. 4.1-c).

Failure usually involves cracking of the solid matrix.

Figure 4.1:

Influence of rock microstructure on failure mechanisms.

|

Petroleum and subsurface engineering involves rock failure at many length scales, from the millimeter-scale to the kilometer-scale (Figure 4.2).

The failure properties of rock (and many other properties too) depend on the length scale of analysis.

Small-scale process zones engage the rock “matrix” properties. Rock cutting at the drill-bit scale and wellbore stability (in homogeneous and non-fractured rock) are two examples. The samples we test in the laboratory are at this small scale as well.

Large-scale process zones involve fractures, multiple sedimentary layers, and faults.

For example, hydraulic fracturing tends to reactivate neighboring fractures in shear and reservoir depletion can reactivate large faults in shear as well.

Recognizing the appropriate length-scale is extremely important to use adequately the rock strength measured in the laboratory and simple mechanical formulations such as linear elasticity.

Figure 4.2:

Rock failure properties are a function of process-zone size and length scale.

|

Rock yield (plastic deformation) and failure can happen due to tensile stresses, shear stresses, compressive stresses, and a combination of the three.

The following sections explore these types of rock damage separately.

Figure 4.3:

Overview of rock failure modes: tension, shear, and compression.

|

Application of tensile stresses (with negative sign according to our geomechanics convention) on a metal bar results in tensile strains (negative too).

In this example the state of stress is relatively simple with tensile stress in the axial direction and zero-stress in any direction perpendicular to the axis of the bar (Figure 4.4).

The maximum tensile stress taken by the bar is called tensile strength.

Metals are usually “ductile” and deform after reaching a peak stress.

When unstressed, the bar in the example figure does not recover its original length but remains with “plastic deformation”.

Figure 4.4:

Tensile strength of a ductile metal bar.

|

The one-dimensional tensile strength test for metals (Fig. 4.4) is not easy to implement in rocks.

You would have to grab the rock on its sides or glue it on the ends to perform such tests. Even in that case, your rock may break at the those “grabbing” points.

One alternative is to “machine” the rock to a convenient shape, so that, you can pull it without using glues or grabbing jaws (shown in Figure 4.5).

However, rocks are not easy to “machine” in general, and thus this test becomes impractical in many situations.

Rock failure in simple tension usually displays “brittle” failure, no plastic strains follow after reaching tensile strength. It just breaks quickly.

Figure 4.5:

Direct tension test on brittle rock. Correct interpretation depends on rock micro-structure and possible existence of pre-existent flaws.

|

The Brazilian test is a convenient method to measure tensile strength.

It uses short cylindrical samples and takes advantage of the shape of the rock specimen to create tensile stresses with application of a compressive force along the sample diameter (Figure 4.6).

A solution of the state of stress within the rock (assuming a linear elastic homogeneous material) yields the tensile strength value  equal to

equal to

|

(4.1) |

where  is the peak compressive force,

is the peak compressive force,  is the specimen length, and

is the specimen length, and  is the specimen radius.

Notice that you have a combined state of stress with compression in the direction of the compressive load and tension in the direction perpendicular to the load along the diameter.

is the specimen radius.

Notice that you have a combined state of stress with compression in the direction of the compressive load and tension in the direction perpendicular to the load along the diameter.

Figure 4.6:

The Brazilian test: sample geometry and example.

|

PROBLEM 4.1: Determine the tensile strength of the shale sample shown in Fig. 4.6. The sample diameter is 1.00 in and the length is 1.00 in.

SOLUTION

The sample dimensions are

in

m

and

in

m

Hence, the tensile strength is

Typical values of tensile strength for cemented sedimentary rocks range from 0.5 MPa to 10 MPa.

Uncemented sediments -very common in sedimentary basins- have zero tensile strength.

Figure 4.7 summarizes typical values of tensile strength for rocks.

Figure 4.7:

Values of tensile strength in a set of cemented rocks measured with direct tension tests (DTS) and Brazilian tension tests (BTS)[Data from Geotech. Geol. Engineering (2014), 32].

The value of the igneous set is an average of granite, latite, meta-pegmatite and peridotite.

The tensile strength of the metamorphic set is an average of gneiss, marble, quartzite and slate.

Compare these values to tensile strength of fused silica: 48 MPa, 304 stainless steel: 505 MPa, and titanium: 1860 MPa.

|

The shear strength of rocks depends on the cohesive strength of the rock  (to be explained later) and the internal frictional strength of the rock.

The frictional strength depends on friction forces, where the force

(to be explained later) and the internal frictional strength of the rock.

The frictional strength depends on friction forces, where the force  needed to displace an object resting on a surface depends on the friction coefficient

needed to displace an object resting on a surface depends on the friction coefficient  and applied normal force

and applied normal force  , such that

, such that

(Figure 4.8).

Hence, if the normal force

(Figure 4.8).

Hence, if the normal force  , then

, then  .

The frictional force

.

The frictional force  increases linearly with the value of the normal force

increases linearly with the value of the normal force  .

.

Figure 4.8:

Friction forces and the friction coefficient. (a,b) Frictional force required to move a solid box. (c) Extension to granular media.

|

Similarly, uncemented sediments can resist shear stresses with the application of an effective “confining” compressive stress (remember the example of the vacuum-sealed coffee).

The maximum shear stress  in uncemented sands is proportional to the normal effective stress

in uncemented sands is proportional to the normal effective stress  through an “internal” friction coefficient

through an “internal” friction coefficient  (red line in Figure 4.9).

The sand is at shear failure when the shear line

(red line in Figure 4.9).

The sand is at shear failure when the shear line

intercects the state of stress represented by the Mohr circle (Check this online Mohr's circle drawer).

intercects the state of stress represented by the Mohr circle (Check this online Mohr's circle drawer).

Figure 4.9:

Frictional strength of uncemented sediments.

|

The Mohr circle represents all possible state of stresses depending on the plane at which you measure  and

and  .

Notice that from all those possible state of stresses, there is just one state of stress that intersects the line

.

Notice that from all those possible state of stresses, there is just one state of stress that intersects the line

.

That plane is the plane at which a shear fracture would form.

Similarly to Figure 4.8, if

.

That plane is the plane at which a shear fracture would form.

Similarly to Figure 4.8, if

then

then  , so the sand has no strength whatsoever without an effective compressive stress.

The friction coefficient

, so the sand has no strength whatsoever without an effective compressive stress.

The friction coefficient  is often expressed as a friction angle

is often expressed as a friction angle  , where

, where

.

Typical values of

.

Typical values of  vary from 0.4 to 1.0.

For example, if

vary from 0.4 to 1.0.

For example, if  , then

, then

.

.

Cemented rocks can bear shear stresses with zero effective lateral stress

(

( for radial effective stress as in cylindrical samples).

Figure 4.10 shows an unconfined cylindrical rock loaded (on the top face) to failure with a compression effective stress

for radial effective stress as in cylindrical samples).

Figure 4.10 shows an unconfined cylindrical rock loaded (on the top face) to failure with a compression effective stress  .

We call

.

We call  (Unconfined Compression Strength) to the maximum compression stress (applied in axial direction) the rock can hold under unconfined conditions.

Axisymmetric tests require rocks samples in which the length should be about twice the diameter to minimize shear end-effects (as in short samples) and buckling instabilities (as in long samples).

(Unconfined Compression Strength) to the maximum compression stress (applied in axial direction) the rock can hold under unconfined conditions.

Axisymmetric tests require rocks samples in which the length should be about twice the diameter to minimize shear end-effects (as in short samples) and buckling instabilities (as in long samples).

Figure 4.10:

Unconfined compression strength: schematic diagram, stress-strain plot and corresponding Mohr circle.

|

Let us now apply an effective compressive “confining” stress

(Figure 4.11).

The measured peak stress is higher than the peak stress without confining stress.

The increment in peak stress will be a function of the internal frictional strength of the rock.

Hence, the maximum shear stress

(Figure 4.11).

The measured peak stress is higher than the peak stress without confining stress.

The increment in peak stress will be a function of the internal frictional strength of the rock.

Hence, the maximum shear stress  will be a function of both the rock cohesive strength

will be a function of both the rock cohesive strength  and the applied normal effective compressive stress

and the applied normal effective compressive stress  through the Coulomb failure criterion expressed in the following equation:

through the Coulomb failure criterion expressed in the following equation:

|

(4.2) |

Figure 4.11:

Shear strength: Coulomb failure criterion. The cylindrical rock sample bears a radial confining stress  .

.

|

With a linear shear failure criterion, a fracture will ideally form at an angle

from the plane where the maximum principal stress is applied. Such plane will also be co-linear with the intermediate principal stress. For a typical value of

from the plane where the maximum principal stress is applied. Such plane will also be co-linear with the intermediate principal stress. For a typical value of

,

,

.

.

PROBLEM 4.2:

In the following uncemented sediment sample and corresponding figure:

a) Which is the point in the Mohr circle with maximum

?

?

b) What is the angle of the failure plane?

c) What is the ratio

at failure?

at failure?

SOLUTION

a) The point in the Mohr circle with maximum ratio

is the one that touches the yield line, for which

is the one that touches the yield line, for which

b) Let us use the figure above to solve the problem.

The top side of the sample is subjected to stress

in the

in the  -

- plane.

The lateral side of the sample is subjected to stress

plane.

The lateral side of the sample is subjected to stress

in the

in the  -

- plane.

The state of stress

plane.

The state of stress

at failure can be located going

at failure can be located going

counterclockwise from

counterclockwise from

to

to

.

The plane of shear failure corresponds to this point and it is at

.

The plane of shear failure corresponds to this point and it is at

from the top side towards the lateral side.

Notice that going from

from the top side towards the lateral side.

Notice that going from

to

to

takes 180

takes 180

in the Mohr circle.

in the Mohr circle.

c) Let us use  (center of the circle) and

(center of the circle) and  (radius of the circle) to express

(radius of the circle) to express

:

:

Sometimes, it is easier to think (and compute) shear failure parameters based on principal stresses rather than on normal and shear stress (Figure 4.12).

Coulomb's failure criterion (Eq. 4.2) can be written as

|

(4.3) |

where  is the effective maximum principal stress at failure,

is the effective maximum principal stress at failure,  is the effective minimum principal stress and

is the effective minimum principal stress and  is the friction parameter function of the friction angle (warning: this is not the same

is the friction parameter function of the friction angle (warning: this is not the same  from the

from the  or

or

space).

It can be shown that,

space).

It can be shown that,

|

(4.4) |

For a typical

,

,  .

The friction coefficient can be calculated from the friction parameter

.

The friction coefficient can be calculated from the friction parameter  with the following equation:

with the following equation:

|

(4.5) |

can also be expressed in terms of cohesive strength as

can also be expressed in terms of cohesive strength as

|

(4.6) |

Figure 4.12:

Equivalency of the Coulomb criterion in terms of shear and normal stresses and in terms of principal stresses.

|

Figure 4.13 summarizes shear strength properties for various cemented rocks.

Figure 4.13:

Average values of cohesive strength and internal friction angle for various types of rocks (original data from [Zoback, 2013]).

|

The shear strength of rocks depends on effective stresses, not on total stresses.

In the field and the laboratory, however, we usually measure total stresses

instead of effective stresses

instead of effective stresses

.

The shear strength of rocks is measured in a triaxial frame (Fig. 4.15-a).

A cylindrical (axisymmetric) triaxial frame can apply independently a confining pressure (that converts into stress)

.

The shear strength of rocks is measured in a triaxial frame (Fig. 4.15-a).

A cylindrical (axisymmetric) triaxial frame can apply independently a confining pressure (that converts into stress)  , a deviatoric stress

, a deviatoric stress  , and a pore pressure

, and a pore pressure  .

.

The confining stress is applied by means of a deformable sleeve around the rock by changing the confining fluid pressure  with a fluid pump.

The confining fluid is usually hydraulic oil or water.

The sleeve makes it possible to apply an effective confining stress and prevents confining fluid to enter into the rock pores and mix with the pore fluid.

The confining pressure is maintained constant in a typical deviatoric triaxial test

with a fluid pump.

The confining fluid is usually hydraulic oil or water.

The sleeve makes it possible to apply an effective confining stress and prevents confining fluid to enter into the rock pores and mix with the pore fluid.

The confining pressure is maintained constant in a typical deviatoric triaxial test  .

.

The pore fluid pressure  is applied with another fluid pump.

A fluid conduit connects the pump with the rock pore space.

Some triaxial frames have two pore fluid outlets to measure permeability during loading. Notice that

is applied with another fluid pump.

A fluid conduit connects the pump with the rock pore space.

Some triaxial frames have two pore fluid outlets to measure permeability during loading. Notice that  , otherwise the sleeve would inflate like a balloon inside the pressure vessel.

The pore pressure is maintained constant in a typical deviatoric triaxial test

, otherwise the sleeve would inflate like a balloon inside the pressure vessel.

The pore pressure is maintained constant in a typical deviatoric triaxial test  .

.

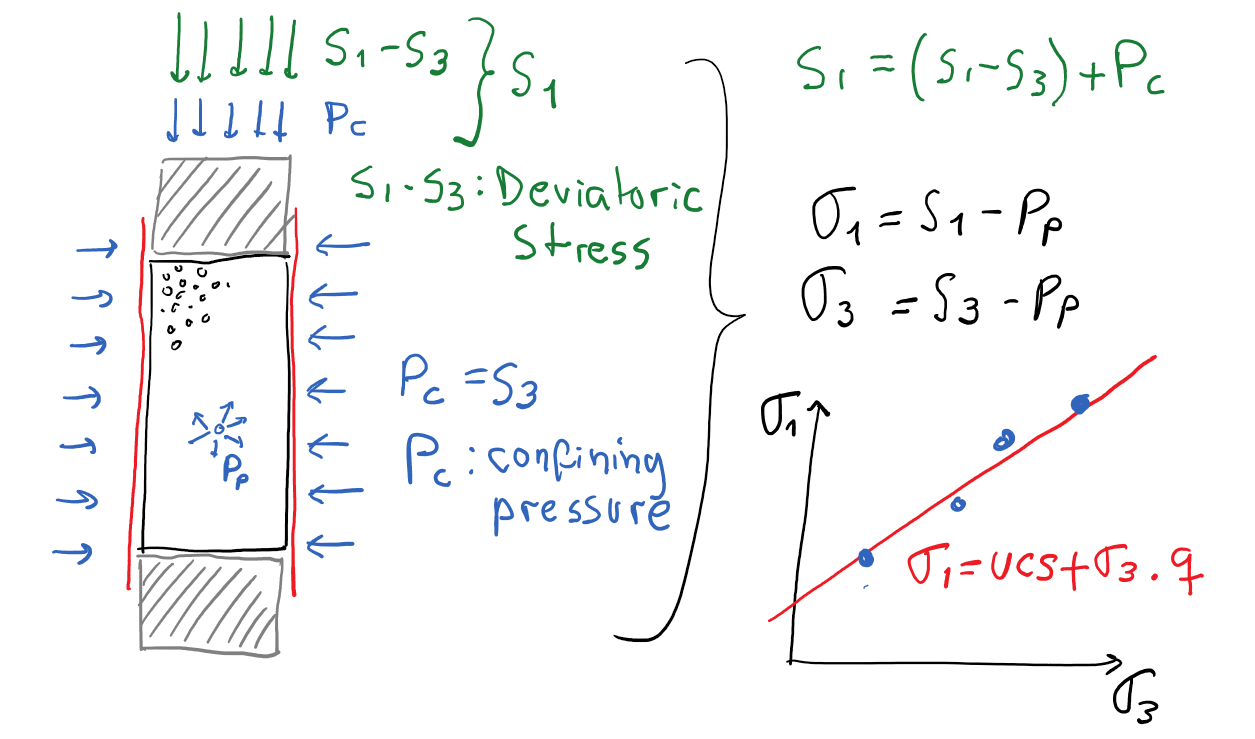

The deviatoric stress  is applied through axial loading with a piston that compresses the rock in axial direction. The deviatoric stress is defined as

is applied through axial loading with a piston that compresses the rock in axial direction. The deviatoric stress is defined as

, where

, where  is the total maximum stress applied with the frame and

is the total maximum stress applied with the frame and  is the minimum total stress (equal to the confining pressure

is the minimum total stress (equal to the confining pressure  ) (Figure 4.14).

Notice that in a cylindrical triaxial frame

) (Figure 4.14).

Notice that in a cylindrical triaxial frame  and

and

. The deviatoric stress is increased with a constant displacement (strain) rate

. The deviatoric stress is increased with a constant displacement (strain) rate

in a typical deviatoric triaxial test.

in a typical deviatoric triaxial test.

Figure 4.14:

Schematic diagram of stresses and pressures in the axisymmetric triaxial test.  : total axial stress,

: total axial stress,  : total radial stress (

: total radial stress ( : confining pressure),

: confining pressure),  : pore pressure.

: pore pressure.

|

The data shown in Fig. 4.15-b summarizes the results of 14 independent triaxial tests:  is the confining pressure for each experiment,

is the confining pressure for each experiment,  is the maximum stress measured at failure, and

is the maximum stress measured at failure, and  is the preset pore pressure.

The data shows that the maximum principal stress

is the preset pore pressure.

The data shows that the maximum principal stress  (measured at failure) tends to increase as

(measured at failure) tends to increase as  increases and tends to decrease as

increases and tends to decrease as  increases.

When the data is corrected to effective stresses (Fig. 4.15-c), it becomes clear that there is just one relationship between

increases.

When the data is corrected to effective stresses (Fig. 4.15-c), it becomes clear that there is just one relationship between

and

and

.

.

The equation that links these two quantities is Eq. 4.12.

It is usually easier to calculate  and

and  from fitting a straight line to

from fitting a straight line to  (failure)-

(failure)-  data, and then calculate cohesive strength from Eq. 4.6, friction angle as

data, and then calculate cohesive strength from Eq. 4.6, friction angle as

|

(4.7) |

PROBLEM 4.3: Fit a line (manually) to the data shown in Fig. Fig. 4.15-c for the Darley Dale sandstone and calculate  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  and

and  .

.

SOLUTION

The red line in Fig. 4.15-c was manually drawn ignoring the point with the highest confining stress.

Hence, this line is accurate only when

MPa.

MPa.

The red line hits the y-axis at

MPa, hence,

MPa, hence,

MPa

The parameter  is the slope of the red line. Taking the entire line length:

is the slope of the red line. Taking the entire line length:

Finally, using Eqs. 4.6 and 4.7:

In the process of triaxial loading, rocks begin by decreasing volume (compression loading) but may show positive changes of volumetric strain

approaching failure.

That is, the rock may start shrinking but it may dilate close to failure giving

approaching failure.

That is, the rock may start shrinking but it may dilate close to failure giving

(dilation is negative).

At this point the rock is not elastic anymore and develops damage inside.

Considerable damage often starts at 50% to 70% of the peak stress.

(dilation is negative).

At this point the rock is not elastic anymore and develops damage inside.

Considerable damage often starts at 50% to 70% of the peak stress.

Figure 4.15:

Triaxial testing. (a) Axisymmetric triaxial frame comprising a pressure vessel, fluid pumps and a reaction frame to apply axial load (not visible in figure). (b) Example results of 14 independent triaxial tests on Darley Dale sandstone as a function of total stresses and pore pressure. (c) Data from -b replotted as effective stresses. Rocks failure is explained through effective stresses, not through total stresses.

|

If compression stresses are high enough, grains can crush filling the pore space.

Pore collapse may happen in nature due to rock burial and also in petroleum engineering during reservoir depletion. In both cases effective stresses increase in all directions.

In long and thin reservoirs, depletion does not cause strains in all directions but predominantly in the vertical direction (Figures ![[*]](crossref.png) and 3.19).

This type of deformation is called “uniaxial-strain” condition.

When effective stress goes over the yield stress (

and 3.19).

This type of deformation is called “uniaxial-strain” condition.

When effective stress goes over the yield stress ( in Fig. 4.16), significant plastic irrecoverable deformations occur and may decrease permeability.

High compression combined with shear can lead to grain crushing at shear and compaction bands resulting in permeability much lower than that of the original rock matrix.

in Fig. 4.16), significant plastic irrecoverable deformations occur and may decrease permeability.

High compression combined with shear can lead to grain crushing at shear and compaction bands resulting in permeability much lower than that of the original rock matrix.

Figure 4.16:

Pore collapse under uniaxial strain condition with grain crushing.  indicates the yield stress at which significant plastic strains happen if surpassed.

indicates the yield stress at which significant plastic strains happen if surpassed.

|

We can combine all rock failure types in a single

plot (Fig. 4.17).

The rock would fail in tension if the Mohr circle (or state of stress) goes further to the left of

plot (Fig. 4.17).

The rock would fail in tension if the Mohr circle (or state of stress) goes further to the left of  .

It would fail in shear if it touches the red line

.

It would fail in shear if it touches the red line

.

Last, it would develop significant compressive plastic strains if it crosses the yield cap (blue line - as you may guess, there is also an equation for it!).

.

Last, it would develop significant compressive plastic strains if it crosses the yield cap (blue line - as you may guess, there is also an equation for it!).

Figure 4.17:

Summary of basic rock failure modes.

|

Most rocks have anisotropic strength properties, thus, strength depends on the loading direction.

The plot in Fig. 4.18 shows anisotropy of shear strength. Consider a rock with well defined planes of weakness in one particular direction.

These plane of weakness may be constituted by fractures, weakly bonded layers, or weak rock layers. For example, there are some rocks with mica foliation that have almost no shear strength whatsoever in the foliation planes.

The plots on the right of Fig. 4.18 show that the shear strength depends on the loading orientation. The sample is the weakest when the orientation of weak planes coincides with the plane that meets the shear failure line, that is

. The sample is the strongest when the orientation of weak planes is perpendicular to the expected shear failure plane.

The videos in this playlist https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLv0npDbE5HXvEdptgajRDG3x-lwmtGDbr show how bedding interfaces affect failures processes under deviatoric stress.

A similar phenomenon applies to tensile strength. Planes of weakness can greatly reduce tensile strength for stresses applied in direction perpendicular to those planes of weakness.

. The sample is the strongest when the orientation of weak planes is perpendicular to the expected shear failure plane.

The videos in this playlist https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLv0npDbE5HXvEdptgajRDG3x-lwmtGDbr show how bedding interfaces affect failures processes under deviatoric stress.

A similar phenomenon applies to tensile strength. Planes of weakness can greatly reduce tensile strength for stresses applied in direction perpendicular to those planes of weakness.

Figure 4.18:

Shear strength anisotropy example in which bedding planes are weaker than the rock layers. [add real data of shales]

|

Rocks have a limited range for which they behave elastically, with recoverable strains.

After a certain limit, termed yield stress, the rock experiences plastic irrecoverable strains (inelasticity) (Fig. 4.19).

Rocks may be still quite strong after reaching the yield stress or even the peak stress if they are able to sustain plastic strains.

Figure 4.19:

Post-peak behavior: elastic and plastic strains.

|

Brittleness characterizes strain localization and energy rate release with failure.

Brittle rocks fail quickly and in well-defined planes. The stress-strain response usually exhibits a well defined peak stress (red curve in Fig. 4.20).

Ductile rocks fail slowly (according to the strain-rate) and distribute strains during failure.

The stress-strain response does not exhibits a well defined peak stress and may get even stronger with increasing deformation (blue curve in Fig. 4.20).

There are several factors that affect brittleness, such as:

- Mean effective stress: higher mean effective stress favors more ductile behavior.

- Temperature: higher temperature favors more ductile behavior.

- Loading rate: lower loading rate favors more ductile behavior.

- Mineralogy: higher organic and clay content favors more ductile behavior in shales, while higher carbonate content favors more brittle failure.

- Specimen size: as the rock sample size increases, more and bigger discontinuities (such as fractures) are likely to be present and contribute to more ductile response because of failure of internal fractures rather than the rock matrix.

- Elastic properties: some carbonate rich shales have a good correlation of brittleness with the ratio

, where the carbonate mineral fraction contributes to high Young's modulus

, where the carbonate mineral fraction contributes to high Young's modulus  and low Poisson's ratio

and low Poisson's ratio  .

.

Figure 4.20:

Brittleness as a function of confinement

|

The plot on the left of Fig. 4.21 shows an example of measurement of deviatoric stress

as a function of axial strain for various confining (minimum) stresses. The data clearly shows a transition from brittle to ductile in Carrara marble.

The post-peak stress-strain behavior can be modeled with plasticity theory.

The simplest plastic model considers no increase (or decrease) of stress once the yield stress is reached (perfect plastic behavior).

As seen in the experimental data, however, the rock may still be able to support stresses after reaching the yield stress.

The rock exhibits “strain-hardening” behavior when it gets stronger with further straining, or “strain-softening” behavior when it gets weaker with further straining.

The increments (or reductions) of stress with plastic strain

as a function of axial strain for various confining (minimum) stresses. The data clearly shows a transition from brittle to ductile in Carrara marble.

The post-peak stress-strain behavior can be modeled with plasticity theory.

The simplest plastic model considers no increase (or decrease) of stress once the yield stress is reached (perfect plastic behavior).

As seen in the experimental data, however, the rock may still be able to support stresses after reaching the yield stress.

The rock exhibits “strain-hardening” behavior when it gets stronger with further straining, or “strain-softening” behavior when it gets weaker with further straining.

The increments (or reductions) of stress with plastic strain

can be modeled through a plastic tensor

can be modeled through a plastic tensor

such that after the yield stress

such that after the yield stress

|

(4.8) |

Accounting for plastic strains is required in rocks with small elastic regions, and in large scale and long-term processes such as fault reactivation, evolution of sedimentary basins, and salt diapirism.

Figure 4.21:

Elasto-plasticity: experimental data and idealized behavior.

|

Now that we know the macroscopic modes of rock failure we can investigate again the actual mechanisms of rock inelasticity and failure.

First, uncemented rocks cannot hold tensile stresses and failure takes place through internal shearing (grain to grain friction and rotation) and grain crushing at high mean compressive stress.

Fig. 4.22 shows experimental evidence of grain rotation in the shearing region of a sand specimen loaded axially (see warm-colored shear band).

Second, cemented rocks can hold tensile and shear stresses.

Most rocks have some level of internal microfracturing or defects that act as fracture tips.

Fractures propagate in three modes: opening, in-plane shear, and out-of-plane shear.

Figure 4.22:

Rock failure at the microscale: mechanisms behind rock failure.

|

Shear and tensile stresses amplify at fracture tips. Therefore fracture propagation usually starts at fracture tips.

The images in Fig. 4.23 show the propagation of fractures after applying a vertical stress on Tuffo carbonate samples with a pre-existing crack (thick dark line in the middle).

Figure 4.23:

Microfracture propagation in cemented rock. Cracks promote stress concentration and intensification at tips. Failure initiates at crack tips. Propagating fractures may coalesce and make a bigger fracture.

|

The coalescence of multiple microfractures can form a macrofracture that defines a macroscopic failure plane (Figure 4.24).

Figure 4.24:

Microfracture coalescence in cemented rock with pre-existing flaws.

|

- The following data presents the results of triaxial tests performed on a dry samples of cohesionless fine sand from the Frio formation in the Gulf of Mexico Basin:

| |

|

|

|

Confining pressure |

Pore pressure |

Peak deviatoric stress |

[MPa] [MPa] |

[MPa] [MPa] |

[MPa] [MPa] |

| 3.4 |

0 |

7.1 |

| 6.9 |

0 |

20.6 |

| 10.3 |

0 |

29.7 |

- Plot the maximum principal effective stress

as a function of

as a function of  for the three experiments. Fit a line that goes to the intercept (0,0) and calculate the shear strength parameter

for the three experiments. Fit a line that goes to the intercept (0,0) and calculate the shear strength parameter  .

.

- Replot the data as Mohr circles, calculate the shear angle

and plot the shear yield line. Does the shear yield line intersect the Mohr circles?

and plot the shear yield line. Does the shear yield line intersect the Mohr circles?

- The file Triaxial-1500psi-raw.dat (uploaded to Github) contains data from a triaxial test performed on a sandstone in dry conditions (

= 0 psi).

= 0 psi).  is the confining pressure,

is the confining pressure,  is the deviatoric stress (

is the deviatoric stress ( ),

),  is the axial strain, and

is the axial strain, and  is the radial strain.

is the radial strain.

- Plot deviatoric stress and strains as a function of time (two plots). Mechanical experiments are usually performed at constant strain rate or constant stress rate. Which case is this? What is the rate?

- Plot deviatoric stress as a function of axial strain. Compute loading Young modulus at 25% of the peak stress and the unloading Young moduli for the two unloading cycles. Comment on the difference.

- Plot radial strain versus axial strain and compute loading Poisson ratio.

- Plot deviatoric stress versus volumetric strain. Does the sample contract, dilate, or both? Explain.

- If the shear strength parameter is

, what is the

, what is the  of this rock?

of this rock?

- Twelve triaxial tests on cylindrical plugs of Berea Sandstone are reported below (Bernabe and Brace, 1990 - The Brittle-Ductile Transition in Rocks, Geophys. Monogr. Serf. Vp, 56, 91-101). (*) This is the axial stress that a load cell measures inside a pressurized vessel (

). For example, the value would be zero for hydrostatic loading (

). For example, the value would be zero for hydrostatic loading (

).

).

| |

|

|

|

Confining pressure |

Pore pressure |

Peak deviatoric stress |

[MPa] [MPa] |

[MPa] [MPa] |

[MPa] [MPa] |

| 10 |

0 |

116 |

| 50 |

0 |

227 |

| 20 |

8 |

119 |

| 45 |

8 |

183 |

| 60 |

8 |

206 |

| 75 |

8 |

228 |

| 50 |

37 |

120 |

| 50 |

32 |

141 |

| 90 |

64 |

161 |

| 90 |

55 |

187 |

| 130 |

96 |

186 |

| 130 |

84 |

207 |

- Plot all data points in a

versus

versus  plot and draw respective Mohr Circles (in Matlab, Python or Excel).

plot and draw respective Mohr Circles (in Matlab, Python or Excel).

- Fit the data to Mohr-Coulomb criterion to compute unconfined compressive strength

and the parameter

and the parameter  through a linear regression. Then, calculate the cohesive strength

through a linear regression. Then, calculate the cohesive strength  and internal friction coefficient

and internal friction coefficient  .

.

- Based on this information, compute the failure angle of the shear fracture you would expect to see in this sample after failure. Draw a sketch indicating the orientation with respect to the axial and radial stress.

- Did pore pressure significantly change the effective stress failure criterion?

Hint: figure out first how to calculate the effective radial and axial stresses.

- Fjaer, E., Holt, R.M., Raaen, A.M., Risnes, R. and Horsrud, P., 2008. Petroleum related rock mechanics (Vol. 53). Elsevier. (Chapter 2)

- Jaeger, J.C., Cook, N.G. and Zimmerman, R., 2009. Fundamentals of rock mechanics. John Wiley & Sons. (Chapters 4 and 6)

- Zoback, M.D., 2010. Reservoir geomechanics. Cambridge University Press. (Chapter 4)

![\includegraphics[scale=0.60]{.././Figures/split/5A-7.pdf}](img548.svg)

is the peak compressive force,

is the peak compressive force,  is the specimen length, and

is the specimen length, and  is the specimen radius.

Notice that you have a combined state of stress with compression in the direction of the compressive load and tension in the direction perpendicular to the load along the diameter.

is the specimen radius.

Notice that you have a combined state of stress with compression in the direction of the compressive load and tension in the direction perpendicular to the load along the diameter.

in

in m

m

in

in m

m

![\includegraphics[scale=0.65]{.././Figures/split/4-TensStrengthSummary.pdf}](img558.svg)

![\includegraphics[scale=0.65]{.././Figures/split/5-Friction.pdf}](img565.svg)

![\includegraphics[scale=0.60]{.././Figures/split/5A-12.pdf}](img578.svg)

![\includegraphics[scale=0.60]{.././Figures/split/5A-13.pdf}](img581.svg)

![\includegraphics[scale=0.50]{.././Figures/split/5A-15.pdf}](img585.svg)

![\includegraphics[scale=0.55]{.././Figures/split/AngleFailurePlane.pdf}](img587.svg)

![\includegraphics[scale=0.65]{.././Figures/split/5A-16.pdf}](img605.svg)

![\includegraphics[scale=0.85]{.././Figures/split/4-ShearStrengthSummary.pdf}](img606.svg)

MPa

MPa

![\includegraphics[scale=0.65]{.././Figures/split/Triaxial-Darley.pdf}](img632.svg)

![[*]](crossref.png) and 3.19).

This type of deformation is called “uniaxial-strain” condition.

When effective stress goes over the yield stress (

and 3.19).

This type of deformation is called “uniaxial-strain” condition.

When effective stress goes over the yield stress (

![\includegraphics[scale=0.65]{.././Figures/split/5A-21.pdf}](img633.svg)

![\includegraphics[scale=0.75]{.././Figures/split/5-StrengthAnisotropy.pdf}](img636.svg)

, where the carbonate mineral fraction contributes to high Young's modulus

, where the carbonate mineral fraction contributes to high Young's modulus  and low Poisson's ratio

and low Poisson's ratio  .

.

![\includegraphics[scale=0.60]{.././Figures/split/5B-13.pdf}](img646.svg)

[MPa]

[MPa] [MPa]

[MPa] [MPa]

[MPa] as a function of

as a function of  for the three experiments. Fit a line that goes to the intercept (0,0) and calculate the shear strength parameter

for the three experiments. Fit a line that goes to the intercept (0,0) and calculate the shear strength parameter  .

.

and plot the shear yield line. Does the shear yield line intersect the Mohr circles?

and plot the shear yield line. Does the shear yield line intersect the Mohr circles?

= 0 psi).

= 0 psi).  is the confining pressure,

is the confining pressure,  is the deviatoric stress (

is the deviatoric stress ( ),

),  is the axial strain, and

is the axial strain, and  is the radial strain.

is the radial strain.

, what is the

, what is the  of this rock?

of this rock?

). For example, the value would be zero for hydrostatic loading (

). For example, the value would be zero for hydrostatic loading (

).

).

[MPa]

[MPa] [MPa]

[MPa] [MPa]

[MPa] versus

versus  plot and draw respective Mohr Circles (in Matlab, Python or Excel).

plot and draw respective Mohr Circles (in Matlab, Python or Excel).

and the parameter

and the parameter  through a linear regression. Then, calculate the cohesive strength

through a linear regression. Then, calculate the cohesive strength  and internal friction coefficient

and internal friction coefficient  .

.