Next: 6.8 Strength anisotropy Up: 6. Wellbore Stability Previous: 6.6 Mechanical stability of Contents

Wellbore stability is affected by various factors other than far-field stresses and mud pressure. Some of the most important factors include: changes of temperature, changes of salinity in the resident brine within the pore space in the rock, and changes of pore pressure near the wellbore wall.

Drilling mud is usually cooler than the geological formations in the subsurface.

Because of such difference, drilling mud usually lowers the temperature of the rock near the wellbore.

The process is time dependent and variations of temperature

|

(6.22) |

where heat diffusivity is

At steady-state conditions, the change in hoop stress

|

(6.23) |

where

Chemo-electrical effects are most relevant to small sub-micron particles, such as clays, the building-blocks of mudrocks and shales. The forces that act on clay particles include (Figure 6.27):

![\includegraphics[scale=0.75]{.././Figures/split/8-InterparticleDistance.pdf}](img1022.svg) |

Shale chemical instability involves changes of the electrical forces between clay platelets due to changes of ionic concentration of the resident brine within the rock pore space. The equilibrium distance between particles is inversely proportional to salinity. Hence, decreasing salinity promotes chemo-electrical swelling of shale (see example in Fig. 6.28). During drilling, the change in ionic concentration in resident brine is caused by leak-off of low-salinity water from drilling mud into the formation saturated with high salinity brine. Smectite clays are most sensitive to swelling upon water freshening and hydration.

Shale swelling leads to an increase of hoop stress and sometimes rock weakening around the wellbore wall. Such changes promote shear failure and breakouts/washouts (Fig. 6.29). Prevention of shale chemical instability requires modeling of solute diffusive-advective transport between the drilling mud and the formation water in the rock. Higher mud pressures result in higher leak-off, and therefore, in more rapid ionic exchange within the shale. The process is time-dependent. Thus, the expected break out angle results from a combination of mechanical factors (stresses around the wellbore) and shale sensitivity to low salinity muds.

![\includegraphics[scale=0.65]{.././Figures/split/7-24.pdf}](img1024.svg) |

The solutions to wellbore instability problems due to shale chemo-electrical swelling are: increasing the salinity of water-based drilling muds, using oil-based muds instead of water-based muds, cooling the wellbore to counteract increases of hoop stress, and using underbalanced-drilling to minimize leak-off of water from drilling mud.

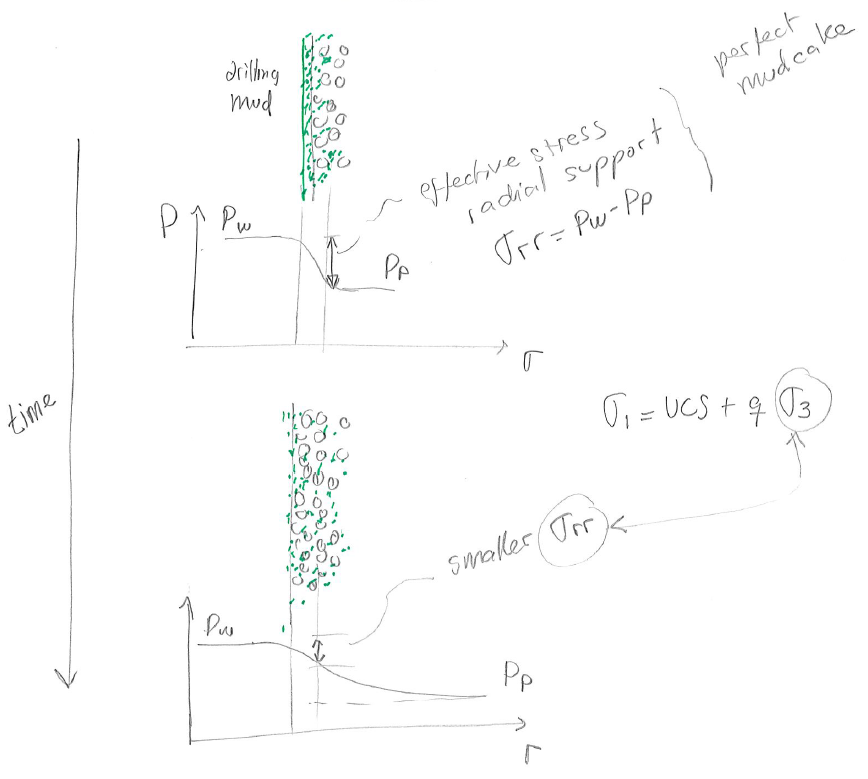

So far we have assumed that the radial effective stress at the wellbore wall is

|